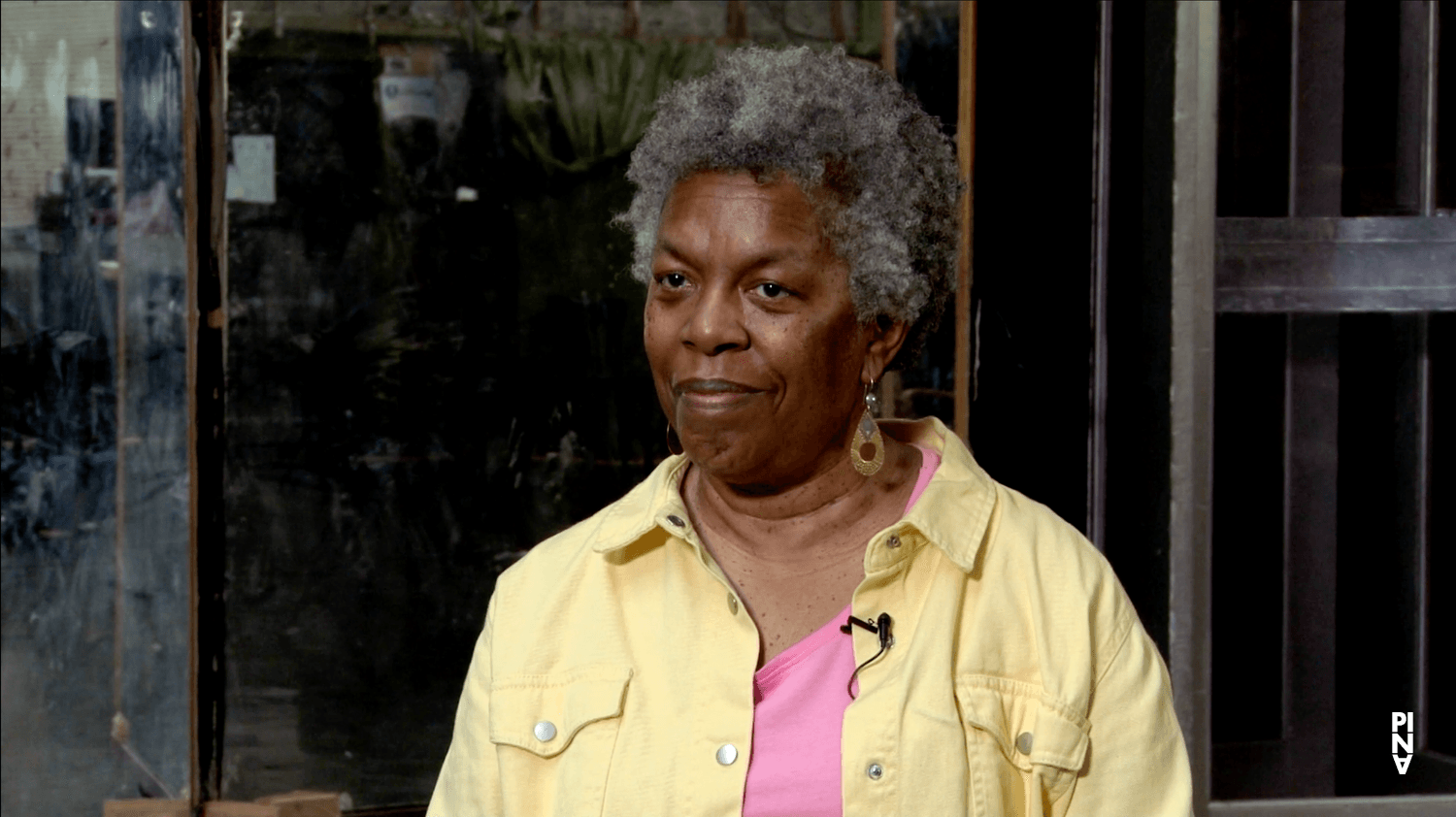

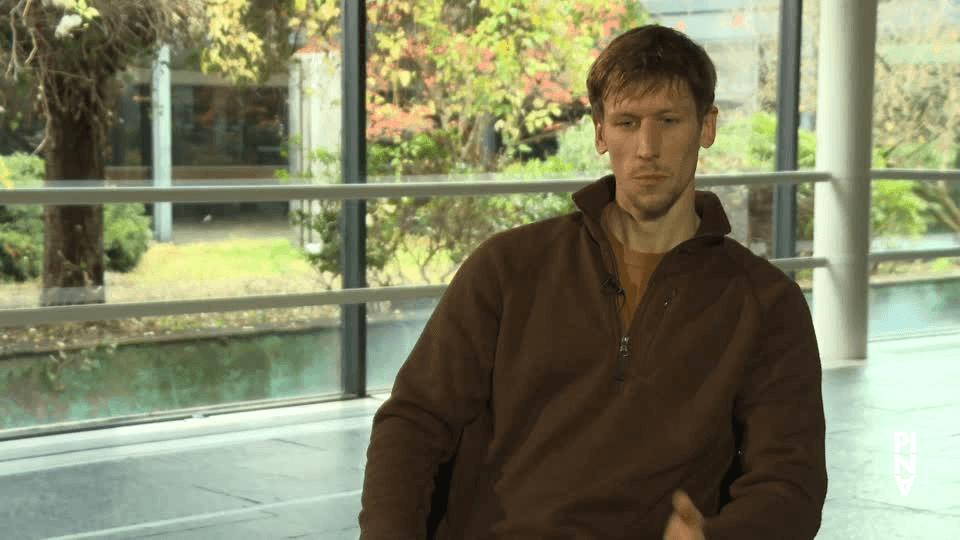

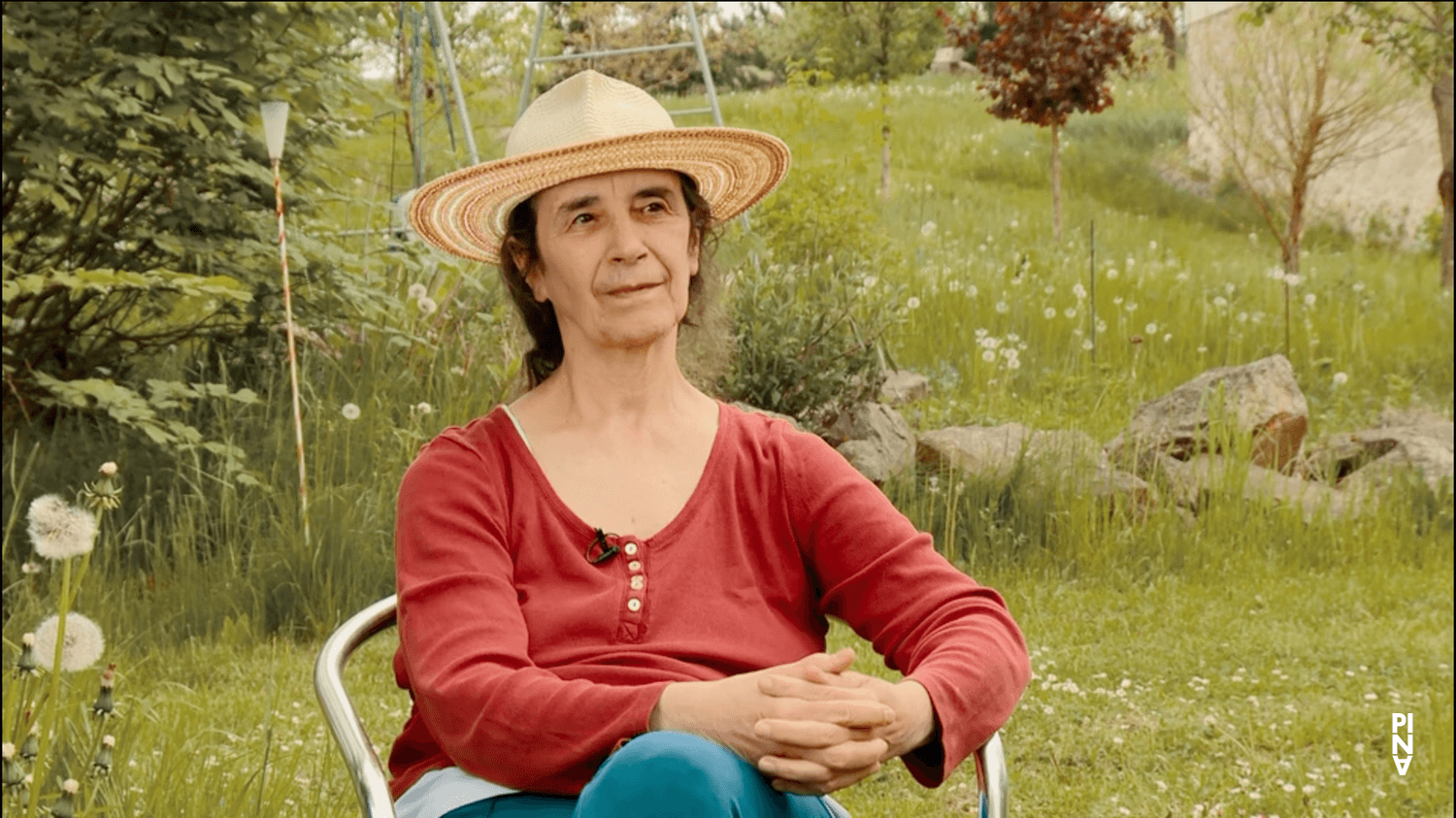

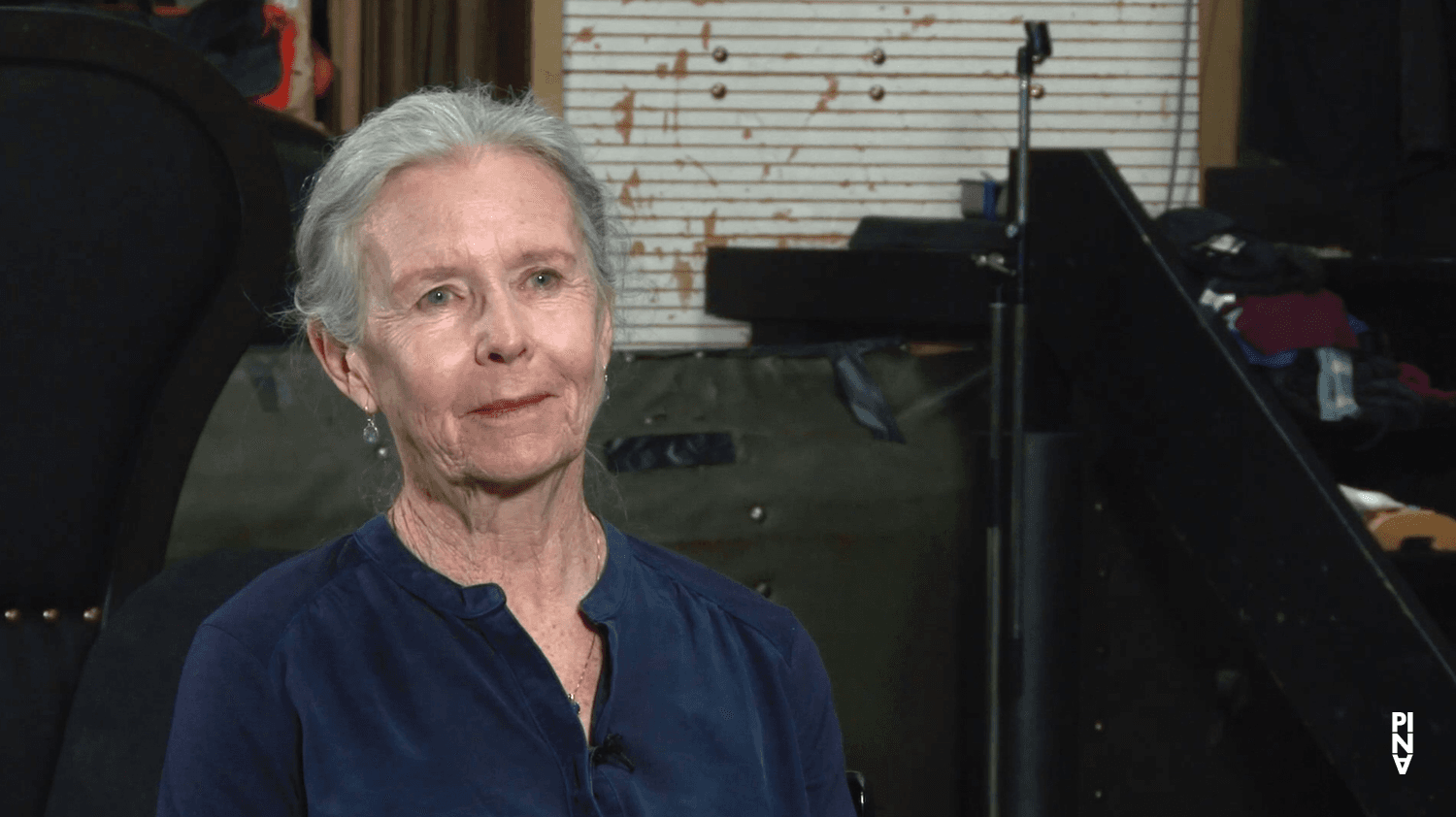

Interview avec Dominique Mercy, 19.4.2022 (2/3)

C'est la deuxième interview de trois, enregistrées en 2022. Dominique Mercy parle de la création d'Orphée et Eurydice et la conversation a pour thème la musique dans l'œuvre de Pina Bausch. Le répertoire jusqu'en 1980 est discuté sous l'angle des méthodes de travail et de la collaboration entre Rolf Borzik et Pina Bausch. Les souvenirs de la période de création de Café Müller, une pièce importante du répertoire, terminent cette interview.

| Interviewé/interviewée | Dominique Mercy |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Caméra | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20220419_83_0001

Table des matières

Ricardo Viviani:

Maybe we can talk about Orpheus. Orpheus first came in the second season of the company.

Dominique Mercy:

We had done Iphigenie auf Tauris, and it was a big successful journey, for my story, and it's most of all, for us a very beautiful experience, really incredible. This together with the reception of the audience, brought up the idea for Arno Wüstenhöffer to propose making Orpheus und Eurydike in the next season. One day Pina was visiting us at our place, and I remember her saying: "You know, maybe there is the possibility to do Orpheus the next season. What do you think? Would you like to do it, what's your reaction?" I was very, very pleased. I liked the idea very much because I had the very strong relationship to this opera. I had done it in the ensemble, it was the opera staged with all the ballet parts, the choreography was done by the choreographer we had in Bordeaux, Adolfo Andrade. I love this opera also because it was sung by one very famous mezzo soprano at that time 1966, 67. Her name was Rita Gorr and Orpheus was one of her leading parts. I remember some rehearsal in which I was not involved, sitting in the studio, there was a little podium where the ballet master would sit and watch the rehearsal. I was sitting on the on the floor, beside her and she was sitting on the chair, singing for us to see how it functions with the ballet and with the ensemble. This woman which I admired, and I had records from her, and I was like starstruck, I loved her, saw her in many different roles in opera. For me, it was such a beautiful, strong experience. So Orpheus was a big milestone, for me in my life. So when Pina suggested that we'd eventually do Orpheus, I was very happy, also thinking that I probably will be the dancing Orpheus. So, we decided "let's do it".

Chapitre 1.2

Dialog with BorzikDominique Mercy:

Yes. Orpheus was the same process that we've been through with Iphigenie. She came with a lots of propositions about movements, and we'd develop it together, like the question and response process. I mean, it's not that she came with a completely done choreography, it was a lot of tries, a lot of suggestions, then we'd try to respond and to develop it and see how things can work. Because our knowledge of German at that time, Malou and I, was not the biggest, so we had to take time to understand the words. For me it was easier than for Iphigenie because I knew the opera so well in French, I almost didn't need any translation, because I really knew it, even now, sometimes when I sing the French version comes up, it comes back quicker than the German one, because it's so much in my head. So, we'd be concerned all the time about the words, by the music; and so it was an easy, flowing process. Together with Rolf Borzik, there was all those ideas of scenery and pictures, which he brought us. It helped us to find different ways and things; by looking at a lot of drawings, pictures, paintings, photos, a lot of different things came up. So there was all this nourishing material.

Ricardo Viviani:

The piece played in that season and it wasn't played until way later.

Dominique Mercy:

It was a double cast originally, on one side there was Malou and I as the first cast, and there was Jo-Anne Endicott and Ed Kortlandt as the second cast. After the second season, Malou and I left the company for the first time. I don't remember if it was right the following season or the one after, that Pina invited us, I don't remember the context, either she wanted to put it again in the season program or if it was for special occasion. But she did again Iphigenie auf Tauris and Orpheus after we left and she invited us. I remember Malou didn't do Iphigenie, this is something to find in the archives, Malou did the Oracle in Iphigenie, and I did Orest. I don't remember if Malou did Eurydike, but Ed danced Orpheus, I didn't dance Orpheus. That season was not the last season, that's something you have to check in the archives, I'm quite positive about it, then for sure it wasn't it wasn't play for a long time until 1991 or 92.

Chapitre 1.3

The Paris Opera BalletRicardo Viviani:

The first revival of Orpheus. Do you remember what was happening, why it came about, how it was playing, then playing in Paris?

Dominique Mercy:

Well we were shortly before invited by the opera in Paris as a company to play Iphigenie auf Tauris, which was related to an anniversary of Christoph Gluck, birth or death, I forgot. I am sorry, but to a Gluck event, therefore we had revived in Wuppertal before, and we talked about this the last time. I think this has was an impulse for Brigitte Lefèvre to invite the company with Orpheus. In Paris was the same process as we did in the revival the year before here in Wuppertal. After we were invited, Brigitte she came up with the idea to revive The Rite of Spring for the Paris Opera, to restage The Rite of Spring for the ensemble in the Paris Opera. So we did, which was an incredible, beautiful and positive experience. Also, working with those dancers you felt they were so thirsty and hungry for this sort of experience, it was very beautiful. For them, coping with the earth and have this such a strong experience about a piece, it was very beautiful. This brought Brigitte Lefèvre to invite Pina for another side, another piece with a different quality, a different aspect of Pina's work. She invited Pina restage Orpheus for the company. Pina was quite happy about it, because she liked very much to work with the company. We accepted the idea, we did the audition, tried to make the best choice we could, and it was an incredible experience again. It was very beautiful. It was a lot of work. The Rite of Spring was based on the same technique, the same background from Pina: the style, the technique, the movements, and what all this demands physically and as technique, but Sacre is more contemporary, earthy, and relates to the floor, which is much easier to approach as an incredible, different and strong experience. WIth Orpheus it's much more delicate because, first they have the feeling it's sort of the classical-language movements, more related to ballet, but still had the same demands of round back, grounded, twisted movements, and this comes up by working on it, is not so obvious at first. So it was a different and not easy process, which demanded time and attention, but it went very beautifully. Then, from the music side, we have this beautiful Balthazar Ensemble from Thomas Hengelbrock, which is a Baroque Orchestra, and has its own choir ensemble. It was beautiful, a really beautiful experience, and very open to the needs we had concerning the music, which quite free and floating. In the Baroque music there's a lot of freedom in the interpretation, but since the dance piece exists, there are some demands which have to be accepted. There are compromises to be found. There are things you cannot change, like some Tempi. I remember, for instance, in the third act, there's this menuet (sings), and the first time Thomas Hengelbrock played it, it was very light and very playful, like a menuet. For him, it was a big compromise to agree with us, we had worked on the only existing version at that time, which was much slower. She was also relating to this atmosphere, which she imagine was the Champs-Élysées, is this sort of very elegiac atmosphere. She made something much, much more floating, but also with a certain cadence, with a certain rhythm. Suddenly, if it comes too quick and too light, it loses what it should be. To be ready to compromise and to come towards each another was a very beautiful experience for me. It was the first time I was I was passing or teaching a role which I created, which I felt a little bit mine somehow, it wasn't mine, but it was mine somehow. That was the first time I was in this position. It was such a beautiful experience to be able to share this with dancers who were really wanting this and trying their best to come the closest to it without losing their own personality, to come as close as possible to what the role is somehow. For me that was a beautiful experience, which was a big help for the following years, and the following experiences I had in that sense.

Ricardo Viviani:

Did you work with the tape or did you work with with the pianist and the conductor in the room?

Dominique Mercy:

With a tape recorder. I don't remember exactly if it was Pina's choice or if it was the only recording available. But we did all the Orpheus, the whole process of rehearsal with the record, as far as I remember, the only existing recording of it by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Which is not a mezzo, which is not a countertenor, but a beautiful baritone. Still the creation was made with the female voice a mezzo-soprano. But all the process was with this recording with Fischer-Dieskau because Pina never liked and fought against. It was sort of an issue, it was easy to solve and everybody tried to be helpful ...

Chapitre 1.4

Alert and aliveRicardo Viviani:

Compromise or collaborate, I would not say that compromises it's not a such a positive word as much as collaborate.

Dominique Mercy:

Everybody tried to collaborate to find the best way to accomplish this. But for Pina, it was always difficult to work with piano alone, she needed the orchestra. She needs that what the orchestra brings, not only a score, played by a pianist, and somebody would be eventually singing. She needed the voice, she needed the orchestra, and so so did we. I mean, it's a huge difference if you build something with all this music being played by a pianist, and you can't have a singer all the time in the studio singing for you, specially these sort of roles, is not possible. So, we did work with the tape. In the opera we had some time to work with the pianist, but since the piece exists already, it's a different issue.

Ricardo Viviani:

She could sense things in all sorts of different levels, visually, acoustically, spatially. So what is my question?

Dominique Mercy:

Maybe part of the question could this issue, you talk about, to be comfronted with this flexibility we had to have. The recording we had was one version of it, but already the staging in Wuppertal was already sharing and a compromise to the version we used to work, because there were different singers, it was the orchestra and the conductor of Wuppertal. Already there, when the piece was still in the process of being created with the first orchestra, the rehearsals with the singers already involved compromise, with the questions from the singers, the orchestra, and the demands we have concerning the tempi we're used to. Either in a dress rehearsal or one of the first orchestra rehearsals, I remember finishing the first act crying desperate in the wings, because I thought, if that's the tempi the conductor wants, I'm not going to be able to dance, because I failed completely. I just couldn't. I was so desperate, I remember being behind the curtain in the corner, crying my soul out, because I felt I'm not going to be able to do it.

Ricardo Viviani:

There's a dialog there.

Dominique Mercy:

That's a beautiful dialog. That's such an incredible and great challenge. And that's why I try to bring the dancer which are involved in this, like now, to make them understand and try to know so well the music, so as to be part of the music. It's either a part of you or you're part of the music, or you are the one, you're the singer, you're the music: you're the one. You can be a little bit forward, a little bit after, but you have to be completely there. Some times it goes too far, because there is a choreography which demands certain precision, it's flexible to a point when it's not any more. It's like if you pull on an elastic, then at one point it breaks. That's something which is also very beautiful, to be so alert and alive. Sometimes it works beautifully and sometimes it's on the edge of a disaster. But that's part of the game.

Chapitre 2.1

Alfredo CorvinoRicardo Viviani:

There are even in a ballet class, there are different ways of doing that, either you hear the piano and you react, or you're on top of it, so that you hit your movement with the note. It's not that you listen and then it comes, it's a split second of an idea.

Dominique Mercy:

Enrico Cecchetti

Ricardo Viviani:

Can you explain?

Dominique Mercy:

Alfredo Corvino: this musicality that drives the movements. You do it on the nose, or it brings you to it? Which gives you the momentum, gives you the dynamic of the movement, to be one with the music. Do you do a grand battement like this (shows) or you do like (shows). You know, it's fundamental. Which makes everything so much easier.

Ricardo Viviani:

You brought the discussion to the current cast we just had in Orpheus. There is set of skills that we have to be aware when we're dealing with live music. It maybe, throughout the years, or it's also a matter of experience, if you work a lot with live music, you know, or if you work with an orchestra or even in music theater, opera and operetta, you're very sensitive to that it. So, is there an extra learning time that is necessary for the performers to acquire those skills?

Dominique Mercy:

Part of this work is made during the rehearsal since we work with the tape. We work with the tape and sometimes with different tapes, like for instance, I use mostly two versions, sometimes referring also to the Paris version with the Baroque orchestra, which also is different. So it's already during this learning process, they have to cope with this different versions. This is one point, but when it's done, when we come to the first orchestra rehearsal, it shows that there was some rehearsals with orchestra missing. But whatever you've been prepared to, there's always a moment, a space where you need to accommodate, where you need to understand. And it's different every night, so you have to be prepared for this. This is also a parallel learning process for those dancers. I think they're probably not used to work with live music.

Chapitre 2.2

Music comes lastRicardo Viviani:

Going forward, Pina had the possibility to create things in whichever way she wanted. But she chose to work mostly with recorded music. Does that points her to a direction to compose her own soundtrack, in the sense that the soundtrack would be as stable as possible?

Dominique Mercy:

I think you can see it, or hear it as such, but I don't think it was about constructing the soundtrack. And the huge difference is that with the time, there were pieces like Orpheus, then there was The Rite of Spring, then there was Bluebeard, then there were those pieces like Kontakthof, which already are a little bit different, Komm tanz mit mir again are different. I am not the right person to talk about the process because I was not involved with the creative process. I danced those pieces as I came back, but I wasn't involved in the process. I cannot really say if there, the music was companion to the rehearsal process, or if the music was already there for Pina, to be a structure to work on, or if there were added afterwards.

Dominique Mercy:

But what I wanted to say, it's that at a certain point she never used the music to start. The more it went on, the more the page which we started on was blank, either the sound page, or the visual page. There was nothing existing. For Pina there was a much more deeper preparation, and motivations for her to bring us the questions, the questions were a result of the preparation work, or thoughts, or whatever. But for us, the only consistent or concrete substance which we had to work on independently of Pina, was the co-productions. If we knew that in next season we will be making a residency in Italy, or in Japan, or Brazil, each one of us could be free to prepare and nourish himself with as much information as we wanted, concerning this country or city. This is one side. For the music side, to prepare, Matthias Burkert and Andreas Eisenschneider who were responsible of the music, could collect and be in contact with archived sounds, archives of that place. But starting the first day of rehearsal, and for quite a certain time, there was no music. Which makes a big difference with the piece we were talking about.

Chapitre 2.3

Pieces of the puzzleDominique Mercy:

The music came later in the process. Like when you put a negative in the water and the picture starts to come up, the first music was there to help us to make things more concrete. Sometimes this music which was used as support would completely disappear, and be replaced by more appropriate music. For the soundtrack, it was necessary for Pina to find it. She worked by selection. She tried to put things together: this with this, and this with that, to see how it's connected. When you put one thing before or after, what does it means? Where are the connections? Where does it bring you? What comes up? What happens, when you open the pot (and smells the food)? Then when she had to decide what was going to stay in the piece, constructing those blocks, she would work on the music. Which music works the best? How the music influenced the work? How do you perceive a scene with this music? And the same scene with that music, what's the difference? What happens there? When this decision is made: "okay, this music is the best for this piece of the puzzle". Now, you take the piece of the puzzle and you want to connect to another piece of the puzzle. It matches, it works, but the music, oh no! The combination that was working on one side, and on the other side, suddenly doesn't work together because of the music. So, you have to make a decision. Do you change the music? Do you change the scene? Or you try to find a music that can connect one piece to the other one, before you change everything. This created the soundtrack. There was no decision of a prior soundtrack for the piece. This music issue was until the last minute a complex decision to make, demanding a lot of work. I think at the end, it became the most difficult thing: to find the right combination. In the old pieces you have this music straight through, and that makes it what it was.

Dominique Mercy:

It was the same thing for the soli. Most of us did our soli without music. After they were done we started to find music that'd fit. Matthias Burkert and Andreas Eisenschneider would always have eyes going around, to try to feel what was going on with each one of us. And they would be attentive and concerned by our first proposals, then at the point that Pina would say, okay, now we have to find a music, then there was sometimes a music which would match right away. I remember well when Matthias proposed Maria Callas for one of my solo in Danzón. I have such a love and respect for Callas that I thought, Oh my God, I'm going to dance to Callas, it's not possible, but let's try. And it was right the first time around. The same thing with this – I always forget the name of this Korean group, which we worked with and some of their music is in different Pina's pieces. I remember I hadn't finished my solo because I was always starting late to work on my dances. Pina would often say, did you I finish? I have to see something, otherwise I cannot use it, if I don't know what's there. I remember also for Kinder I just had what I thought'd be a beginning of the solo. It gave me a key, I started and Matthias put this music of this Korean group. I first thought it was a sort of Romanian gypsy thing, and it worked right away. It gave me the key to finish the dance, to finish the solo. It gave me what I was missing. For the the solo of Fensterputzer, we tried thousands of music, maybe I am exaggerating, but we did try a lot of music before we found the right one. In the last piece in como el mosquito en la piedra I was also sort of late. I think it was Andreas that proposed the music, and I felt very good. But still, Pina wasn't sure and she wanted to try [other music]. I thought I had finished it, and she was just looking for the music. I did it seven times always trying another music, and I kept thinking that the first music was the right one. And we sort of left at it. At the end, she agreed to come back to the first music. That's the process. Twice she had a big confidence in me, and gave me a big present. I didn't know how to to solve it because it was to a musician, which I respect very much. The first time was a solo in Masurca Fogo with a Fado of Alfredo Marceneiro. During a rehearsal already on stage she told me: this is one of your favorite singers! It was also in the last solo of Nur du a music which Matthias proposed from Marceneiro. It was so beautiful, incredible. So she gave this music to me, and told me to try to do something on it. I didn't have anything else. She just gave me the music, and said please try to make something. It was the first time in this context, I tried to compose something on the music which was already there. I had much respect for it, then what came out is what came out. The second time was for Kinder, for the second solo, which was the music of this wonderful Hungarian musician. Not very long, but incredible music starting very soft and increasing afterwards. She gave me this music and asked me to do something and I thought, I don't know if I can. It was a big thing. It was very motivating, and something came out of it, which I'm happy about.

Dominique Mercy:

Little bit more than 20 years. I'm 24 or 25.

Dominique Mercy:

it is some range of time which makes a difference.

Chapitre 3.1

in ParisRicardo Viviani:

This is the season of 1975, 1976. In 77 and 78 you go to Paris and start a company. I was surprise that Bénédicte Billiet was already in it. Right, in Paris?

Dominique Mercy:

That's where we met.

Dominique Mercy:

Jacques Patarozzi. Yes.

Ricardo Viviani:

Jacques Patarozzi you knew from Paul Sanasardo.

Chapitre 3.2

Peter Goss & Dominique BagouetDominique Mercy:

Malou was there, and Héléna Pikon was studying with Jacques in Paris. And she was just starting dancing, very young then studying dance. Dana Sapiro was the partner of Jacques. That's how I met Bénédicte. Then when we were invited by Pina to dance Orpheus and Iphigenie, she came to Wuppertal to see me dancing in the piece. We met in Paris because she was working with Peter Goss and Dominique Bagouet. That's how we met. In Paris, I did work with Peter Goss as well. We did the one evening dancing at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris.

Dominique Mercy:

I was taking class with him, and he asked me, and I worked with him in his performance.

Ricardo Viviani:

I remember taking classes with Peter Goss, maybe in the eighties. That's about ten years later. But it was basically Limón based, right?

Dominique Mercy:

Very nice teacher, and have a good work on the Limón technique.

Chapitre 3.3

Stravinsky & Kurt WeillRicardo Viviani:

And here with Wuppertal and Pina, you kept a bridge and came to perform in Orpheus and Iphigenie... and she was going on and created the Stravinsky evening and Todsünden which you also didn't participate in the creation but eventually learned it.

Ricardo Viviani:

Well, Renate was before, wasn't it.

Dominique Mercy:

The same season.

Dominique Mercy:

We stayed just that season and then we left again.

Ricardo Viviani:

So meaning that the first production that you created again with Pina was Renate?

Dominique Mercy:

When we first came back I learned different pieces. I learned Sacre, I learned Bluebeard, Todsünden.

Dominique Mercy:

Kontakthof came after.

Chapitre 4.1

"Blaubart"Dominique Mercy:

I learned all those pieces. I remember when I first learned Sacre at one point there is a moment: there is a strong sequence with the men, and then we run to the back, all gathering at the back. That's when the chosen one comes out and lies down on the red material, the red dress. I remember running to the back there and telling myself: I'll never do it again. Although I loved it, it was beautiful. But I remember the first performance, it was like, Oh my God! The other strong experience was when I saw that it. It was just amazing. It was Bluebeard. When I first did Bluebeard, when I learned Bluebeard, and Jacques also learned it, it was for both of us an incredible experience, it was very strong. And that's the season that we started with Renate.

Ricardo Viviani:

Can you maybe remember what impressed you or what was strong about Bluebeard? I remember when I saw already in the eighties.

Dominique Mercy:

Everything: the music, the choreography, the conception, the experience, the inside experience. What you experiment, what you feel in this journey. There are so many things happening in this confrontation, this relation. These men and women in love and hate and despair. This despair released. It's all so strong and this atmosphere are very, very strong. Because I had seen it first in Paris. The company performed it in Paris as we were there. I remember being there and the reaction of the audience: it was like, oh my goodness! People were not fighting, but really arguing between each other in the audience with strong reactions. People hating it and people loving it. I found it to be mind blowing. It was just fantastic. And after seeing it, then be able to learn it and to do it on stage was an incredible experience.

Ricardo Viviani:

There's a path that follows the music, and then in Blaubart there is this deconstruction of it.

Dominique Mercy:

It's a deconstruction, but this deconstruction is the result of a necessity. I don't think that it was a basic guiding idea. It is the result of a necessity, still the music is the ground of the piece. There is a necessity of this guy, he wants to understand it, to hear them, re-live these scenes. So he pushes the button and goes back, and is confronted with this situation, this moment. And tries to understand or tries to escape.

Ricardo Viviani:

There is a literary base for it.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, there're different sources relating to the Bluebeard stories. This is on one side, but the music is a strong material for structuring the piece. So maybe this is one step, in the process of how to use music. Definitely Renate was one of the pieces, if not the first piece to start to work without the music. Again, I don't know enough about the process of Bluebeard's to really talk more about it.

Chapitre 4.2

Renate EmigratesRicardo Viviani:

So, let's talk about Renate. From today's perspective, I've never seen Renate on stage. It hasn't been performed that much. How was it to construct it? You just said that you started working without a music in Renate.

Chapitre 4.3

Drawings of Rolf BorzikDominique Mercy:

Yes, we did work without the music. One of the supporting elements was all these comics. Which you find also in the program. These sort of love story comics: "I love you. - Oh no, you don't love me. - Oh Dear! - He is going with another one. Oh, my God!" I remember when I first came back, we were staying in Pina's flat. We hadn't found a place yet. So, for a while we stayed at Pina's. And I remember one of the first things she showed me was a drawing from Rolf, and said: "You'd be such a beautiful angel". It was these drawings of angels by Rolf Borzik. That was one of the first things she showed me. Saying that there was this idea of angels being in different places. It was not a theme on which we work on us as such, it was just an idea. But we did work on a lot of movements, and questions. She started to ask questions. And it was not so evident. It was strange, you didn't know if you were able to respond to this. What does it mean? How do you know what to do. It was unknown country, very experimental. Which became even more so, when we did Macbeth. This was clearly in that direction, incredible. But, with Renate, it was confusing somehow.

Ricardo Viviani:

But love was a big theme. One of the things that strikes me was Mari Di Lena's love letters.

Dominique Mercy:

Of course, that's what I mean when I'm talking about this naive way of approaching love through those comics. That was one of, not motivation but the structures of the piece. Trying to find something similar. That's why, I think, she called it in an operetta because of this naive approach, like in this scene of those those guys coming out with the Gone with the Wind music. (sings) Each one of the men would come out sort of like a cliche: playboy, or men [with confidence]. The piece started like this, had these flirting moments between the audience and us as an angel. There're this sort of naive levels of talking about struggling with love successfully or not. I remember there's this scene on this incredible music, which I forgot was the composer is. Where suddenly I, as a sad or desperate angel, go from one woman to another one being carried. I suddenly go back to more positive way of of seeing life. This is something which was not the easy to find. I remember I was very skeptical. Pina gave the idea of what we could do. So we went into it with the material we had, we went from one thing to the other, and we finished it. I was very skeptical and I didn't know if I liked what we did. And she said, well that that it! That is what I missed, that was what I was looking for – this sort of more dramatic or desperate way of struggle with love.

Ricardo Viviani:

The coquetry, the girls and boys in the repetitions in this scene of the deconstruction of relations between them.

Dominique Mercy:

That's this approach to the theme with very naive and primary eyes, through those comics. At one point there is this scene like a love school, of how to behave, how to be sad, how to try to be charming, how to flirt, how to seduce. There is this teacher and this test, and then we try to make the best out of it, to repeat.

Ricardo Viviani:

It very much resonates to the idea of teenagers trying to understand the world, the world of love and relationships.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, absolutely. This is actually what it is. When you see those comics from the seventies, sixties and earlier, it's all those little things, [the drama].

Chapitre 4.4

"Macbeth"Ricardo Viviani:

Right after that, we come to Macbeth, we come to Bochum, we come to this connection. Do you know a little of the background? How Pina was approached for it?

Dominique Mercy:

Well, first of all Pina had to accept this co-production with Bochum – to make a piece with some dancers from her company with different people who were not dancers. There was an opera singer, but most of them were actors. The idea of this co-production and her approach, was not to make nor stage a theater piece, but try to work on the theater piece. To make something about it, to make a piece about a piece.

Ricardo Viviani:

Do you remember reading the text of Macbeth?

Chapitre 4.5

Work with actorsDominique Mercy:

Course, as they probably do in the theater with actors, we had a table reading. Trying to find what's important for us in the text. Which words? Which sentences? How we relate to it? What we think makes sense to work or not to keep? We underlined the text, each one in a different way, then we talked about it. We tried mix things as our work substance.

Ricardo Viviani:

Were you living in Wuppertal and going back and forth?

Dominique Mercy:

Back and forth. Rolf Borzik was driving us. And that's the first time that we, I, Malou and Thusnelda were living in this apartment. Rolf helped us to find this apartment. There was a wall here with a door. We stayed here for that season, then we left, and then I came it back. Rolf and Pina would come pass by with his Saab, his car at that time. Malou was not in the piece, so I would go every day with them to Bochum. Back and forth.

Ricardo Viviani:

Having worked with all different sort of people, with dancers, with musicians, with opera singers, with the choir of an opera, working with actors, these are all very different approaches. You have to find a way of talking to those people, to communicate with them. Actors have a tendency to base on their work on the text.

Dominique Mercy:

I see what you mean. For all the respect and love I have for her, this is something which we were always confronted with Mechthild Großmann. Because Mechthild, less than Hans-Dieter Knebel who was also a member of the company after Macbeth, had always more to say or more to be explained to try to understand regarding a text, or how to understand a situation. As a dancer, you go much more instinctively or dare to experiment without knowing, because the body needs to understand, in combination with the brain, of course. But, it's true actors have this approach of trying to understand, or go deeper in this situation. Sometimes can be a handicap to a natural, or more spontaneous reaction, which can be very rich and bring you much further somehow. But because the starting point was the text, the piece, this was never a problem, and it was very logical to go back to it or try to refer more to it at one point or another. But what I wanted to say, was that was also one of the reasons why Pina went even more into this process of questions. Because the people which were involved in the process were not all dancers, so they wouldn't be able to answer the question as dance or proposing movements. So that's why Pina went very much more into those questions, trying to find questions which would motivate more natural movements, like of being angry, be sad or be nervous, or how to say good morning. Those things which everyone can answer in their own way. You don't need to be a dancer for that. I must say, this was so rich, incredible from such a diversity going through this process with this mixture of people, actors and this one of opera singer. Some of us: Jo Ann Endicott, Jan Minarik, Vivienne Newport, and I were the only dancers. This combination was so much fun. It was a great time. It was so rich, creative and we had so much material, with crazy ideas. We started a little bit for Renata, but for Macbeth it was really fantastic that Rolf Borzik came with so many clothes and props. Anything, it didn't matter from which period of time, which style. We could use everything, also furniture. Everything was there in the room. So we had the craziest ideal combination, it was just incredible. It was just like being in front of a treasure and picking out things, and enjoying it so much. So, we had so much material, if she had wanted to, she could had made three pieces out of it. So much material, it was so rich, so incredible. It was an incredible period time. Also, we had a real fun, yeah, it was beautiful. Sharing this experience with non dancers, it was an enrichment as such.

Ricardo Viviani:

I wonder how this constellation came to be, how the casting was was done?

Dominique Mercy:

I don't know. I don't know if it was in combination with – what was the name of the director? Claus Peymann? [Peter Zadek]

Dominique Mercy:

Maybe it was common choice between him and Pina. Pina knew Mechthild because she had been doing the second part of the Seven Deadly Sins in Fürchtet Euch nicht. Hans Dieter Knebel was originally there to help. He wasn't meant to be part of the cast. He was there for us, to help, bring coffee, he was a baker. A trained baker, I don't know how it came to be, because he was an amateur actor, I think he asked if he could just be part of the game. So it happens that he finished in the piece and having real role in it. Pina liked him very much and she took him in the company afterwards.

Ricardo Viviani:

In Macbeth, you have all this disparate bits and pieces.

Chapitre 4.6

Rolf BorzikDominique Mercy:

It's all Rolf Borzik, I remember he brought very early in the work the furniture. Even before we started to rehearse it. I remember sometimes they went ..., together also with Jan Minarik. Because Jan was very near to Rolf and Pina, at that time they shared ideas, they went searching for ideas, for place ideas for the set. Rolf had the conception of the set, and already at the start of the rehearsals we already had this iron bed, the shower, all what's now on stage as a furniture, as a structure were already in the studio. Also very early we had the idea of this floor with this carpet with these red waves pattern.

Dominique Mercy:

There was two more dancers involved with Bochum, I think.

Ricardo Viviani:

I think Anne Martin even came for one rehearsal.

Dominique Mercy:

I don't remember.

Ricardo Viviani:

She might have told me that in one of her visits she went there for one day.

Dominique Mercy:

I remember Meryl Tankard. She made sort of an audition in Bochum. That's why she landed in Cafe Müller, because she wasn't in the company at that time. But I can't remember Anne somehow. Sorry.

Dominique Mercy:

There were two more then so involved with Bochum. One was Marlis Alt, but then she had a lot of back problems and she quit. She left the company because of her back problems, and there was also some [conflict] with Pina, so she left. Renate was her the last piece, if I remember well. And Tjietske Broersma was also originally cast for Macbeth, but then it didn't work and she stepped out. So since most of the company was here [in Wuppertal], Pina asked three choreographers: Gigi Caciuleanu, Hans Pop who was her assistant, Gerhard Bohner to make three different pieces for the company. She had this idea with Rolf Borzik. They made a red thread you could find in all pieces: like a table, chairs, maybe a mirror, glasses, a coat, red shoes, red wig, a blackout. Different things which would be interpreted or appearing in each piece, but they were free to use it. Just those things which you might find back in each one of the pieces. During he time that we were busy with Macbeth, the company was busy with those three different choreographers, working on three different pieces. After we finished Macbeth, there were two weeks left before the premiere of Café Müller, and I remember Pina asking us about it. We had our problems with Jan Minarik, our relationships, and our different ways of dealing with the work. She knew that we were leaving again. When I think from Pina's side, there's no price for it, there're no words for our connection. Still she wanted to do her own Café Müller in the full evening, and she asked us if we were willing to do it. We said yes, of course, then we started to work on Café Müller, we did it in two weeks. Which later became what it is.

Ricardo Viviani:

Purcell and the music that she brought into the piece. Did Pina bring the music?

Dominique Mercy:

She brought it, saying: "I have some music which I really love but I never dared to use because it's so beautiful and so ... She proposed the music, and it was so beautiful. And it was so obvious. This is where my memory sometimes misses: I wouldn't be able to say how much we did worked with or without the music. Still, this was one of the first things Pina proposed. And also Merryl Tankard who had auditioned in Bochum and whom she really liked, she wanted her to be part of us. It was in the room and obvious that it would become quite a personal and intimate piece.

Ricardo Viviani:

Both music pieces were very familiar to Pina Bausch: both Henry Purcell Dido & Aeneas and The Fairy Queen.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, she had worked with Kurt Jooss in this festival which they did the The Fairy Queen together. [Schwetzinger Festspiele]

Ricardo Viviani:

So there was something that she has been carrying with her ever since she was 19 years old.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, exactly. That's probably why she didn't dare to use them, because this music had already a past, a concrete support she was referring and relating to. So she probably needed that time to be able to use it again.

Ricardo Viviani:

At that point, the Lichtburg was very new. Part of it was already being used for rehearsals.

Dominique Mercy:

I think we did inaugurate the Lichtburg with Café Müller. Maybe already with Renate a little bit. I remember it became very obvious, during rehearsals of Renate, that we needed a bigger space because of an idea which never took place. The idea from Rolf Borzik was indicated by the Balllettsaal, our studio in the Opera House. When we worked on Renate we wanted to have an extra stage on the stage, and you couldn't really make it in the studio. So, they were really searching for a bigger space where you could eventually sketch or start to build a set, before you get on stage, to work on thoughts of spaces. I don't remember if we had some end-rehearsals of Renate in the Lichtburg, before to go on stage, or if we did have the first rehearsals with Café Müller there. But still it was connected to Renate.

Ricardo Viviani:

Your bouncing off the wall with Malou it's something that you can do with just one wall, but the running from one side to the other needs a room.

Dominique Mercy:

That was just a little structure. There are pictures which we shows it. It was a wood frame with some weights, so that it doesn't move too much. With some short walls to give us the idea of the space, and the table. But the idea of all the chairs came at the last moment. There was the table, but the idea of the chairs came at the end. We had finished the piece and we thought: "Okay, it's nice, but something is missing somehow," and Rolf Borzik came up with the idea of putting chairs in the middle of the room.

Ricardo Viviani:

More chairs, because there was already some, I suppose, because the other pieces had some?

Dominique Mercy:

Not really. Not really. The idea to have this handicap with the chairs and somebody helping was from Rolf Borzik. And since nobody else was there, because it was a very intimate rehearsal we said "then you'll have to do it." And because he did it in the rehearsal, it was clear that he would have to do it on stage. Then it was clear that that's what was missing, but before that the piece was done, actually.

Ricardo Viviani:

One interesting thing is that in the program, neither Rolf Borzik nor Pina Bausch are listed, so there was an intention of having the piece with you, Malou Airaudo, Jan Minarik, and Meryl Tankard. Four people, and the program then got printed that way.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, because till the last minute, Pina wanted to have the possibility to escape, I think. And during the whole process, if you listen to Pina Bausch, she would say I was there because Malou couldn't remember the steps, so to help her during the rehearsal; and if you listen to Malou, she would say I was doing everything so that Pina could be on stage with us, because actually it was a very strong wish from us to have Pina on stage with us. That's true. Then it became so obvious that there was no piece without those two women. I mean, it's so obvious ... and Rolf Borzik, of course. Regarding Rolf from his side I don't know, I don't remember, but from Pina's side, she wanted to have the possibility to keep free till the last moment. Maybe because it might make a difference if her name was already announced, I don't know. She always wanted to be part of us, so often it became impossible because it's so complicated to have an external eye and still be involved in the piece.

Chapitre 5.2

Work processRicardo Viviani:

Was there a process in Café Müller, possibly very fast, of posing situations or questions, and then going and working on it. Things like sitting on the table or your kiss with Malou Airaudo .

Dominique Mercy:

I don't remember any questions for Café Müller. It was just the music enough, and the situation, our relations. Ideas and question from Pina in terms of "let's try this or can you do that? How about a moment like this?" But not like a formed or concrete question like in other pieces. Like, how or what are you seeing?

Ricardo Viviani:

Observing or different ways of kissing or different ...

Dominique Mercy:

It was looking for moments, looking for full situations or solutions.

Ricardo Viviani:

So in a sense, it became a very quick and very spontaneous, very creative process.

Dominique Mercy:

Very quick, organic, and also those moments of silence. I mean, maybe because it came so naturally, my memory sort of like integrated and forgot about it. It was as if it was there. Always. Yes. Everything was there.

Ricardo Viviani:

And then just give it a form or giving a presence or giving a manifestation.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes. This moment at the table with Jan Minarik, Meryl Tankard, and I when Malou is on the floor. It's something that was so natural and suddenly Meryl starting to cry. Yeah, it's true, I mean, when you think about it, it's a little bit like discovering what was already existing somehow.

Ricardo Viviani:

After Rolf Borzik died. Do you remember his death, when you were probably in France, Paris?

Dominique Mercy:

We were in Paris and we came for the funeral with Malou.

Ricardo Viviani:

And Pina Bausch created 1980. You're not part of it. But then there's the first performance in Nancy and then the South American tour. When did you decide? And how was coming back to do the performances in Nancy, and then then going to the American tour?

Dominique Mercy:

To do the performance in Nancy was sort obvious, because there was this Café Müller and Pina asked us to come and do it. It was sort of obvious and such a beautiful experience. Oh, my God, for the first time to do it in a completely different structure, in this old garage with those big windows. The audience was outside in a "L" formation in bleachers. The ground with concrete. Concrete floor! Concrete walls! But it was really a beautiful experience. But what was the question?

Ricardo Viviani:

So, she asked you to come. But then in Nancy, it's an interesting thing because you don't have the walls, the doors, exits.

Dominique Mercy:

Yeah, that's what I mean. There's a whole different concept. How to use this place, which is not the set, but which is a beautiful place. And it was indeed a beautiful experience to put that piece in another structure. We just only had the turning door, the chairs of course, the table and that's it. And this idea to be in a sort of aquarium, because you had the audience outside and we were in this big hole which was a mixture of a workshop for cars and also exposition showroom. You could see through, because it was all glass, metallic smooth frame with some big glasses. Exposed at both sides. I remember, normally at one point I come through the door, without the door, I sneak into the space without being really seen. Then at one point being there, and I remember I had a huge way from all outside slowly coming along the wall until I could enter the room somehow with Jan Minarik. It was a beautiful, beautiful experience.

Ricardo Viviani:

Do you remember having enough time there? I mean, there is never enough time in the rehearsal.

Dominique Mercy:

I don't remember, it was quite obvious anyway. I mean, that was this space and we had to do the best out of it. That's it, you don't need days and days for it, you know.

Ricardo Viviani:

Yes certainly, Pina was there before in 1977 in the big opera. The festival is a big thing.

Dominique Mercy:

With The Rite of Spring and The Seven Deadly Sins.

Ricardo Viviani:

And there's all sorts of venues and I always kept wondering how this choice was made to perform in the garage, which I am just as fascinated as you say you were at that point. Certainly at that point she would have her pick of a space. So, she chose that space.

Dominique Mercy:

Oh, yes, probably. This also is one of the things I completely forgot. I mean, how this came to be, how did Pina choose this? For me it was just a fact, we were there and we had to do it in this beautiful space, but how do we manage that? What's the best? Is that the front? Is this the front? How do we take the audience in account? Do we forget them? What's where? What's the exit? An entrance possibility. Which door is there? A door? That door. So there's one door there. Okay, This, uh. The floor is what it is. I mean, you keep it the way it is, so you'd be a bit careful. Maybe a little bit, but. But, uh, yeah, I mean, all those things, but. But we're in a very natural and organic way somehow, you know? And so things in that case, things becomes very quick, sort of obvious.

Chapitre 5.3

South American tourRicardo Viviani:

Then there's the South America Tour. You first land in Curitiba, and then go on?

Dominique Mercy:

Well, I don't remember the order, but it was there was a security by Porto Alegre, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Lima, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Santiago. They were doing Kontakthof, I think.

Ricardo Viviani:

Stravinsky evening and Kontakthof which you probably had to learn?

Dominique Mercy:

No. Well, I did learn it but I didn't have to learn it then. Because Pina asked me to do the tour, but as an Inspizient [Stage Manager]. I was giving the cues for the lights and pulley chains. I don't remember doing it for the Stravinsky evening, but I was doing it for Kontakthof. Don't ask me why. But I still have all my notes regarding the fact that I was being stage manager for Kontakthof. I was dancing Sacre, yes, it's true. But I think there was no Café Müller yet.

Ricardo Viviani:

There was a Café Müller, but it was a three piece evening ...

Dominique Mercy:

Café Müller, Zweiter Frühling and Rite of Spring. Yeah. So that's it.

Ricardo Viviani:

Also in different orders.

Dominique Mercy:

That's what also the pattern we did in Israel: Café Müller, Zweiter Frühling and the Rite of Spring. So I was doing Sacre but there was nobody for ... , or I don't know why, I was the stage manager for Kontakthof. It was a beautiful tour, I remember. Anyway, I love South America. It was my second tour in South America because I have I've been doing a big tour with the Ballet Théâtre Contemporaine going to many places in South America.

Ricardo Viviani:

That was probably five years before?

Dominique Mercy:

Maybe more. It was probably in 1969, 70.

Chapitre 5.4

Consolidating the repertoireRicardo Viviani:

This constellation Sacre and Café Müller. That's what I'm trying to piece together when those things came together. And there are also programs that list alternative casts for Café Müller in Colombia.

Dominique Mercy:

Alternative cast for Café Müller?

Ricardo Viviani:

Yes, in Colombia there are two names for the people.

Dominique Mercy:

Oh, you have to show me this.

Ricardo Viviani:

I found it very fascinating.

Dominique Mercy:

I can't remember. I remember Pina being replaced as she was pregnant.

Ricardo Viviani:

Israel.

Dominique Mercy:

Well, Israel. I remember Malou Airaudo being replaced already at that time for different reason. But for this tour? I think with the time it became more clear to Pina that it was time ... , or she didn't find the necessity to keep some pieces, when she started to build a repertory. From the eighties on, she realized that there were some pieces she felt that were not necessary to keep in the repertory. That's why, I mean she started with some of them, like Ich bring dich um die Ecke, and so forth and so on. But like Wind von West, was one of the first to be put on the side, and then with the time it was also clear that Zweiter Frühling didn't have a big reason to stay in the repertory. She found more interesting to confront Café Müller and Sacre with each other .

Ricardo Viviani:

Do you have any remembrance, parallel to the work on stage, how those experiences were nurturing what was to come?

Dominique Mercy:

I loved tango, but I think we made it as we went back to Buenos Aires Bandoneon. About the tango scene in Buenos Aires: we were more connected to it when we came back already with the piece, I think. But at that time, during this tour of course, you look for tango when we go to Buenos Aires, and then you try to connect to what makes the flair of a city, of a country. And they were all different, but I think also, probably has to do - but maybe I'm making a wrong step, this is something to be really careful with. But, Pina Bausch during this tour had met Ronald Kay in Santiago del Chile . And I think this South American culture, through Ronald Kay became more present for Pina, and all the music which you have in Walzer, which comes after Bandoneon is also somehow connected to Ronald because there is a lot of Colombian walzes and South American music involved. So, I think he's is also responsible for the title of Bandoneon, one of his first contribution to Pina's work. But it's not that we did parallel to the tour, specific work regarding a next creation.

Voir aussi

Mentions légales

Tous les contenus de ce site web sont protégés par des droits d'auteur. Toute utilisation sans accord écrit préalable du détenteur des droits d'auteur n'est pas autorisée et peut faire l'objet de poursuites judiciaires. Veuillez utiliser notre formulaire de contact pour toute demande d'utilisation.

Si, malgré des recherches approfondies, le détenteur des droits d'auteur du matériel source utilisé ici n'a pas été identifié et que l'autorisation de publication n'a pas été demandée, veuillez nous en informer par écrit.