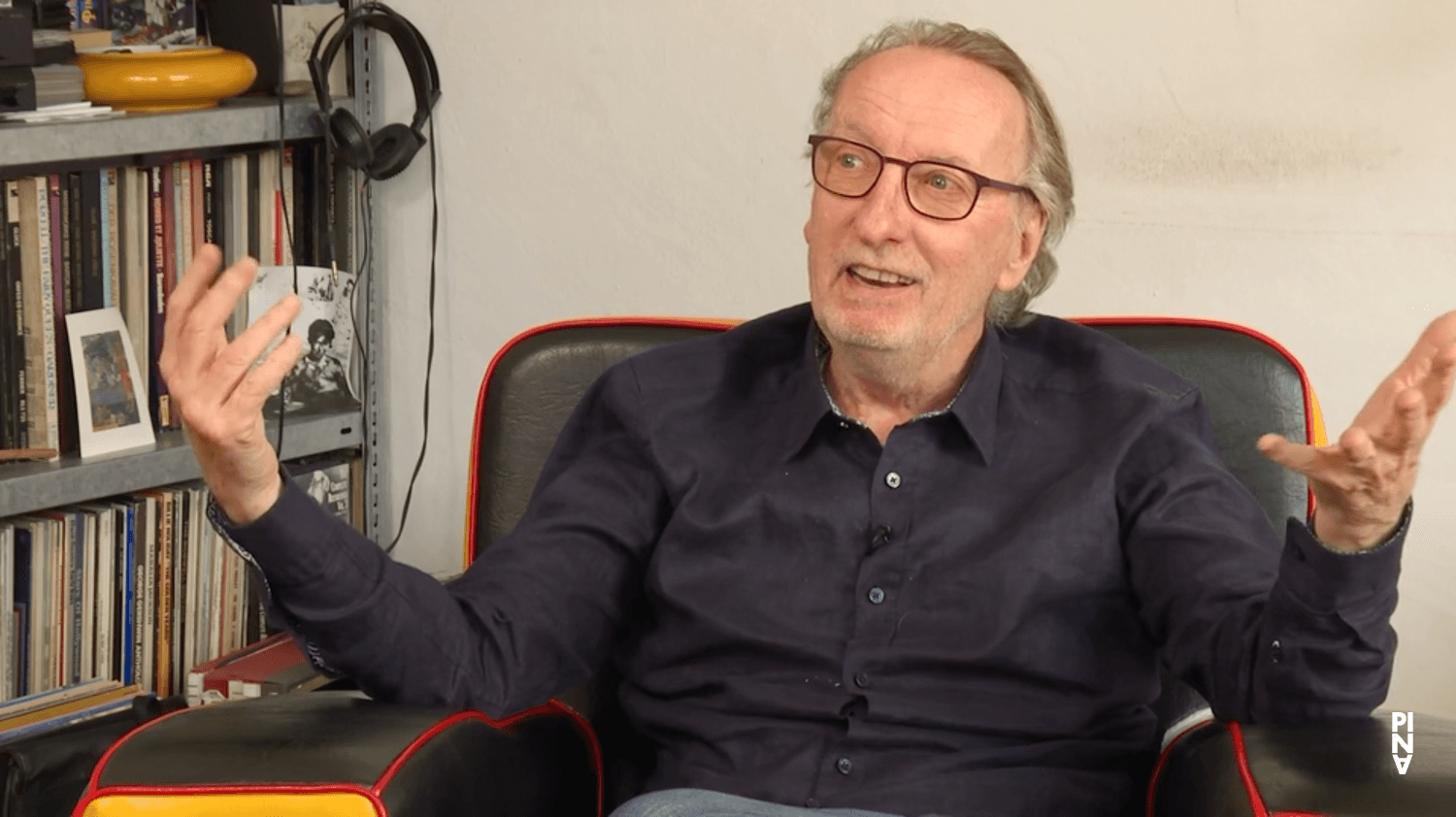

Interview avec Dominique Mercy, 3.4.2022 (1/3)

C'est le premier entretien d'une série de trois, qui ont été enregistrés en 2022, dans lequel Dominique Mercy raconte comment il est tombé amoureux du monde du théâtre et de l'opéra : "mes terres enchantées". Avec la bénédiction de sa famille, il a commencé à prendre des cours de ballet à l'âge de six ans. Il a ensuite rejoint l'Ensemble Ballet de Bordeaux. Puis il a découvert la danse contemporaine en travaillant pour le Ballet Théâtre Contemporain : "Je me suis enrichi, émotionnellement et physiquement". C‘est là qu‘il rencontre Manuel Alum, qui lui présente Pina Bausch à Saratoga Springs, New York ; elle l'invite à être membre fondateur du Tanztheater Wuppertal. Dans cette interview, il parle également des deux premières saisons de créations au sein du Tanztheater.

| Interviewé/interviewée | Dominique Mercy |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Caméra | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20220403_83_0001

Table des matières

Chapitre 1.1

Warrior in the Polovtsian DancesRicardo Viviani:

I showed you earlier today, this wonderful document that I found in the archives by Raimund Hoghe. Through that article, I learned that you start dancing very early. You started taking dance classes, so by the time you were 15 and you've got your first job, you were already a well trained dancer.

Dominique Mercy:

I don't know if I was well trained. I was a thin teenager that had the chance to get invited for a try in this company. I don't think I have some pictures, but I remember one of my ballet evening for the company, at that time we were also doing ballets for opera and operettas, and there was one or eventually two dance evenings in the year, unlike now where there are more regular performances of dance evenings. So the first thing I can remember it was the Polovtsian Dance from Borodin. Which was a restaging from the choreographer and ballet master from the company Paul Greenways. I was one of the soldiers, but I was 15 years old and skinny. I already had legs, which were well trained, but the torso from there to there, was from this skinny little teenager which didn't have muscles. I remember going to the gym to try to build a little bit more muscles on the top. I remember this position with a big spear, the nice legs, but the torso just like this thin, and I was supposed to be a savage and very courageous warrior.

Chapitre 1.2

Germaine PopineauDominique Mercy:

I started when I was about six years old, and as it's written in this article, the teacher was the daughter of one of the school masters and also a piano teacher. I also took piano lessons with her. She opened a small studio in the area where we were living and I was there for five years. So, I started when I was six years old and then when I was 11 years old, she sincerely said, and I thank her for that, that she had the feeling that she couldn't bring me any further and that I should look for somebody else to teach me: another school or something, which we did. Then, it didn't work out the way we thought. My mother and I thought that shouldn't be a problem to find a school, but I wasn't accepted in any of the schools we went to with my grandmother. My mother was busy with the shop in the suburbs from Bordeaux, in Talence. She didn't have the time to bring me in this research, so I always went with my grandmother. We went to the conservatory, to two or three different schools, but they didn't accept me. For what reason? I don't remember. Then, through my father, who was in a club of people from other cities. My father was "ch'ti", as we call in France. It means a person from the north of France, near the Belgian border, in Roubaix. So, he was the member of this club or circle, from "ch'ti" people in Bordeaux, and another member was an opera singer, quite famous at that time Michel Dens.

Dominique Mercy:

Through him my father found out that the wife of the director of the theater in Bordeaux was an ex-ballerina, who was a privately teaching in the studio from the theater. She didn't have an official school, it wasn't the academy, but she taught there. So, through this relation from my father to this opera singer, we made an appointment with this woman. We went there to the office of the director, she wasn't there, I think he was there – I remember vaguely. She had high heels, always, and I remeber those steps in the corridor "tum tum tum", then appears this fairy, all in a lilac petticoat dress. She had a beautiful blond hair in a nest, she had something from Elisabeth Schwarzkopf – her face was very regular and beautiful. She had also the same lilac color shoe, just like the petticoat dress, and she had this shawl everything in one color. She appeared like a fairy in the clouds, she took me to the studio where she kept me doing things, barres and different things. I don't remember exactly, but for quite a long time. At the end, she was really enthusiastic and said: "This boy is dance reincarnation". So I'll take care of him or you have to send him to the conservatory in Paris. Since that was not an option for my parents to send me to Paris, the conservatory was out of our game, that was not possible. We decided that I would go to her, to this most beautiful woman: her name was Germaine Laland, her artistic name, when she was still dancing – you can't invent this, was Germaine Popineau. That's an incredible name.

Chapitre 1.3

Extraordinary teaching styleDominique Mercy:

She was wonderful, we were using the studio from the company in the theater. Most of the time I was, as usual, the only boy or there was maybe another one. We were sometimes four students, sometimes three, sometimes five, but always a small group. She was teaching for 3 hours, without music, singing throught it all. It's was just marvelous. It was for me, never a question of feeling strange or complicated about it. It was just just marvelous. At one point in the middle of the class, she would stop and say "we do the orange pause". Everybody would bring an orange and we just sit down, talk, have a rest, and eat an orange. We'd make a break in the middle of the class, and then we start again. I never met anybody doing this – I think Jean Cébron did it sometime: we were doing the barre, then we'll go to the center, do few things, and then we'd go back continuing the barre, it was quite amazing. Sometimes we'll have a class, she called the "barre à terre" - floor work, sometimes in another studio, which was used by the chorus in the theater. - I have a small film about this, actually, given to me from a friend in small format. Weather permiting, we'd go to the terrace in the director's apartment in the theater – now it doesn't exist anymore. After so many years, we went 2013 there to do Café Müller and Sacre, and I could dance again on that stage, it was beautiful. I went to visit every corner of the theater, which I knew so well. That was a part of my life: going everywhere in the theater. On the very top floor, there was a terrace on the front side of the building, at the left there was the apartment from the director and she brought us up there, and we'll do the barre on the floor, on this terrace. It was wonderful, we had we had a lot of fun. Another the part that was so incredible was that I've been right away involved in the theater life. I loved opera, I loved music, so it was for me coming in my enchanted lands. They knew that I loved opera so much, going to class, I would take every chance to go to the wings to see rehearsals, to see performances from up there, from the bridges, or in the wings, when I was allowed. When they realized that I was so involved with the performances, they always gave me free tickets to the performances. I saw so many operas, operettas, and theater, there was always a ticket for Dominique in the box office. It was wonderful. They were some magic, wonderful moments.

Ricardo Viviani:

Also a wonderful chance to have an education in the theater and learning about the repertory that was being shown. This was probably the later half of the sixties?

Dominique Mercy:

1965 untill I left for the other company in 68. I stayed three years in that company.

Chapitre 1.4

Enrico CecchettiRicardo Viviani:

Did you realize or did they ever talk about what kind of tradition of ballet there was there?

Dominique Mercy:

We never talked about it. I sort of recognized it when I met Corvino. It was very clear that Alfredo Corvino was in the Enrico Ceccetti tradition. I recognized so many things I knew without knowing that it came from that tradition. I think she, Germaine Lalande had learned in this tradition. The other woman which I mostly took classes afterwards, which was the ballet master and choreographer Françoise Adret in Ballet Théâtre Contemporain, also came from this very simple, very practical and structured technique and the musicality. When I met Corvino and worked with him, I recognized so many things, it made so much sense to me.

Ricardo Viviani:

Being the only man in a room full of women dancers, there's also the things that only boys need to do, like the big jumps and so. Did she give you that?

Dominique Mercy:

She gave the small jumps, but of course in a limited amount of time. I remember going into "manège" and to diagonal with "saut de basque" and things like this, but we didn't really go deeper. This I did automatically and much more consistently when I got into the company, into the ballet ensemble from the theater. Which was so nice, because I was part of the theater, of the fauna, of the people from the theater. I did some, not extras [Statisterie], but little parts. The very first thing I did, still while taking classes with Germaine Lalande, not yet in the company, was to do the prologue of The Nutcracker. I was very proud of it. I remember being in front of the closed curtain and this man Drosselmeyer would bring the Nutcracker, and I was supposed to play a little child, to do little jumps trying to get the nutcracker. This just to say that I was already involved with the dancers and the company. So when I was engaged officially, I already knew everybody, and they knew me. So there was this connection and being taken in, and being helped with technical issues. Sometimes they would come and give me some advice, apart from the teachers, they were helping me. It was beautiful.

Chapitre 2.1

Richer emotionally and physicallyRicardo Viviani:

When was the point that you became interested in the modern side of dance?

Dominique Mercy:

I think it was in Ballet Théâtre Contemporain. Before that, I was completely involved with ballet. I had a first impression, I did have the first strong impression seeing pieces from Maurice Béjart. I was maybe 16, 17, I was really impressed. It was interesting because it was one piece with the Wesendonck-Lieder [Mathilde - Maurice Béjart 1963] which was connected with opera singers and more theatrical stuff. I liked this very much, but since I was so much into classical music, I didn't have the curiosity to go for this. How can I explain? Well, let's put it little bit differently. When I was in the Ballet Théâtre Contemporain, the first moment which I could relate myself to modern dance was with Manuel Alum. The repertoire we were doing in the Ballet Théâtre Contemporain was mostly using a classical language, neo-Classic, or even jazzy. I remember Brian MacDonald did a piece on Archie Shepp music – which I love, it was more like jazz. It is funny, but this question never occurred to me, as far as I remember. I never had the feeling I had to choose. It's just something which came on top of this thing which I was involved with. But clearly, the first emotional physical sensation of discovering a new approach of dance, a new technique was with Manuel Alum. At that time, his class had a mixture of balletic – that came from Cecchetti, because he was very involved with Maggie Black, mixing this with his style, and Paul Sanasardo – whom I didn't know at the time, and Martha Graham. They had a softer approach to Graham, I discovered afterwards because I had no idea of Graham technique at the time. I didn't have a clue of the German tradition and that I didn't know anything about. For me, this encounter with Manuel was very important because I discovered something different, it didn't pull me away from ballet, but I had the feeling I got richer, emotionally and physically there was something there that I could assimilate. The second time related to the physical experience was with Pina Bausch. But then coming from this other side of contemporary modern dance: from the German side, which I didn't know. Between these experiences, I had another artistic shock, mixed with knowledge. Because they were performing in the Maison de la Danse, where the Ballet Théâtre Contemporain was based, where we had our studio, I could see the preparation, I could see rehearsals during their tour and I saw they were doing a ballet class before they started to dance, and it was the Cunningham Company. For me, it was incredible, because of the juxtaposition from the artistic experience as an audience, the company looked a little bit different: there was Carolyn Brown and all those incredible people, and of course Merce Cunningham himself; but seeing those people traditionally known as modern dancers doing the ballet class before the performance was something which made sense for me somehow. It made me feel, without really realizing it, something very organic in the approach. I remember Manuel Alum telling me in a trip: "you know, I think you're one ballet dancer that has the weight of a modern dancer". For me that was a completely natural approach. Probably thanks to the people that helped me to grow in dance, my teachers, I never had the feeling of being asked me to be a ballet dancer. That's where I come back to Alfredo Corvino and this tradition – this is what it is – the body is a tool and the structures to be able use it. Not getting on top of technique and try to present something just to be beautiful. I feel blessed and lucky to have been to have been growing up in this environment.

Chapitre 2.2

Ballet Théâtre ContemporainRicardo Viviani:

How was the transition from Bordeaux to Ballet Théâtre Contemporain?

Dominique Mercy:

OK, the transition. I can't say she had a specific role in the decision, although somehow yes, you know. But my mother always tried to make me feel and understand, that for her, it was clear that she didn't see me having a glorious career as a ballet dancer in this little town and this little company. She she wanted something more consistent for me. I think she even wrote to Béjart. She thought that this ballet divertissement was not really consistent, there was something missing for her. But this is one thing, I can't remember how far I was influenced by this or not. What I can say is that at one point Françoise Adret was invited as a guest choreographer in Bordeaux. I think the first things she made was the choreography for Carmen, which was influenced by Roland Petit which she had been working with, which I liked very much. She was invited again to make a ballet evening. I don't know if she made one or two ballet evenings, I can't remember now. Anyway, there was a strong connection between us. I liked the way she was. I liked the way she teached, I thought it was neo-classical. Nothing special, but I liked that. There was something that gave me the feeling that'd bring me or bring us somewhere else. She had a lot of confidence on me, and she gave me already a lot of responsibility in the choreography. Thanks to her, I was doing quite soon after entering the company leading roles. I think she came twice. The second time she came was in the season before I left the company. And there was this project of Ballet Théâtre Contemporain taking place, and since she was involved into the project, she asked me. I don't remember if she first talked to me or to my mother. Because I was 17 and at that time you had to be 20, not 18 like now, to be an adult. She told us about this company, what it was to be, she didn't mention it, sort of a revival of the idea of the Diaghilev company, where like every new ballet had stage design from sculptors, painters and with contemporary music, like Ferrari, Xenakis, Stockhausen, Malek, Ligeti and all those people. And that was the idea, to create a new repertory, which was really interesting. The only thing for me, which I was a little bit skeptical and I didn't know, was my attachment to classical and lyrical music. When she said that, apart from Stravinsky which was the earliest, there would be mainly contemporary music. I didn't know what that meant for me. I did the audition, I was taken. So I went there, that meant that I left the company in Bordeaux, that was a big shock for my teacher and for the director at that time. I remember, and I still have a letter which they brought to my mother. They really supported me, making it possible to engage such a young man in the company with 15. I needed the support from them, and they were always behind me, supporting. I think they were quite sad and injured. When I said I would leave, I was about to become officially a soloist, because of what I was doing in the performances. I still have the letter they wrote to my mother, it was like being invited, and going away with the silver, knives and forks and dishes. This was in 1967, when the company Ballet Théâtre Contemporain started in 1968, I was part of it.

Dominique Mercy:

I've been really lucky. As far as I remember and along my way, I have been always surrounded by wonderful people, who helped me. I'm not the only one, but I belong to those people who had the luck of meeting the right people at the right time somehow.

Ricardo Viviani:

Was it mostly Françoise Adret's choreography at the Ballet Théâtre Contemporain, or were guest choreographers there as well?

Dominique Mercy:

She was actually the ballet master. I don't know how her position was called, because the official director of the company was Jean-Albert Cartier, who was later director of the Paris Opera Ballet. She was his right hand, I don't remember her official position title. But she was the ballet master, insofar that she was teaching very regularly, among other teachers. She was the official teacher of the company, and she was also a choreographer. She did a few choreographies, but she was not the official choreographer of the company. There were many invited choreographers.

Chapitre 2.3

Maison de la CultureRicardo Viviani:

Was it a regular company in a city theater, doing the operas and one or two ballet evenings?

Dominique Mercy:

No, that was actually the exciting thing about about this company. It was actually the first officially created independent contemporary dance company in France. We were not attached to any theater, we had a house which was La Maison de la Culture in Amiens, which had a performing stage, but didn't have a studio. I mean, we took some space and made a studio out of it, but it wasn't constructed as a dance studio. We arrived there and we have had to find out how we're going to live in this place? We knew we had a stage, a house, dressing rooms, but we didn't have a studio. So they made for us a closed space, which was formerly an exhibition space, and that was our studio. We weren't attached to any theater, and with the official lyrical season. It was the only company beside the opera and the ballet from the Opera in Paris was financed by the state, by the government. And that was the only company officially financed by the government as a contemporary, independent company.

Ricardo Viviani:

This is about ten years before Jack Lang started with all the choreographic centers?

Dominique Mercy:

That was still André Malraux. Not sure. Anyway, these maisons de la culture that became a tradition in France, was something André Malraux made up. I forgot. I should maybe search for it, if it was still under Malraux, if it was one of his ideas. André Malraux was for a long time a very important Culture Minister from Charles de Gaulle. Or just after him, I don't know, this is something which may be worth to find out. But it was way before Jack Lang.

Ricardo Viviani:

Anyway, there were also some of the American choreographers touring Europe, Louis Falco, Paul Taylor, and Merce Cunningham as you mentioned. Did you see those as well?

Dominique Mercy:

No. I saw, as I said before, the only performance I saw was the Cunningham performance. Louis Falco I discovered much later, through one of his wonderful dancers Lar Lubovitch. Whom I loved and was such a beautiful person. I never worked with him. We shared space and time together, we took classes together, but we never really worked together. Also Jennifer Muller, but that was a bit later, after I met Manuel Alum, which then brought me to the States and then I met those people. But in France I didn't have any idea about Louis Falco, and as far as I remember, he did some choreography for the company, but after I left, so I never met him. And at that time I don't remember having heard about him.

Dominique Mercy:

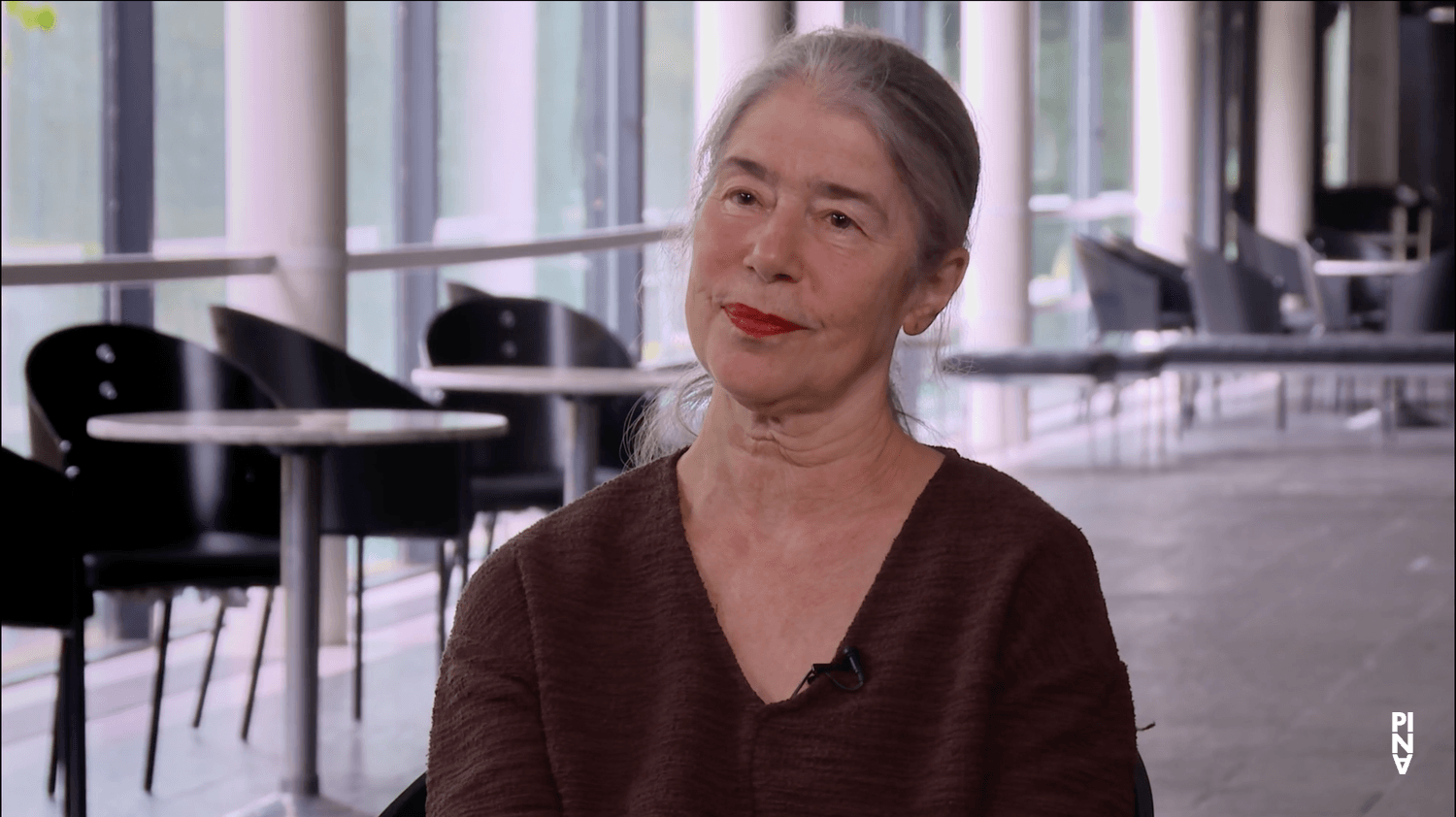

Malou, came to the company a little bit later, in the first season still, but a bit later. She was still busy, you would have to ask her. But I remember she came a little bit later, and the first memory I have of Malou was of her sitting in the doorframe watching a rehearsal, as a latecomer. That's the first image I have from Malou. We became somehow the best of friends. We dance together, and became best friends since then. Only later we went a little bit further with our relationship, but first we were very good friends.

Ricardo Viviani:

If we're in 1968, there were two or three years before Manuel Alum came, right?

Dominique Mercy:

Manuel Alum must have been invited in either 1970 or 71, I can't remember exactly now. Actually, the first idea of Françoise Adret was to invite Paul Sanasardo. Who she knew either from the Batsheva Dance Company, or from a different way, and because Paul couldn't come, he proposed Manuel. She invited Manuel Alum and that's how it all happened.

Ricardo Viviani:

Did Manuel Alum make a piece?

Dominique Mercy:

No. He was just teaching.

Chapitre 3.1

Manuel AlumRicardo Viviani:

During his time teaching, did he invite you or talked about Saratoga?

Dominique Mercy:

Actually it went in two steps. First he came to teach and we had this matching contact. I mean there's something that was really beautiful about our encounter, and what I found and worked out in his class, and so the person. The next step was for different reasons. One of the reasons was the wish to work with Manuel. Malou left the company in Amiens to work was Manuel. That's when it would be beautiful to have the version of Paul Sanasardo imitating Manuel, and you know how beautiful he likes to speak. Because he always laughed, saying that Malou was looking for Manuel's company, and he liked to mention that Manuel didn't have a company. It was that Paul gave him the chance to work with the dancers who were there. Malou went there to work with Manuel, and shortly before the vacation in 1972 – it must have been 70, 71 probably because she'd been there for a while, working and struggling in New York. Then she told me that Manuel was preparing a new evening, and he would like to work with me. I liked Manuel, Malou was there, it was the summer vacation, I never went to the States: there were so many good reasons for me to say yes. So I went there. It was the summer of 1972. I flew to New York, and then I met one of the dancers from the Ballet Théâtre Contemporaine, who was staying in New York and received me, because that was my first time. Brought me into New York, brought me to the bus station, the Greyhound bus station downtown.

Dominique Mercy:

To take the bus to Saratoga Springs. For me, it was marvelous taking this Greyhound bus and going through the States to Saratoga Springs. For me in my memory was a little bit like I went through the old United States, but it was just from New York to Saratoga Springs. As I stepped out of the bus, it was evening and there were those three persons waiting for me: Manuel, which I knew, Malou, which I knew, and another young woman, which I didn't know. I thought it might be Manuel's sister, because she this sort of bony face. It happened to be Pina, which I didn't know she existed. The dancers, the students and teachers were spread out in different villas in Saratoga. Saratoga Springs has these beautiful villas all over the place, with these big spaces between. It's a beautiful place and they will spread out to different villas. Malou and Manuel were in one of the villas with Pina, and the three of them were waiting for me. We spent the whole time that summer, working in Saratoga, in this villa together. You get to better know the people when you spend the daily life with them.

Chapitre 3.2

Pina Bausch's teachingRicardo Viviani:

I think it was the third year that Paul Sanasardo was there. One of their activities, why Paul and his company were there, was also teaching classes, and Pina was there to teach as well.

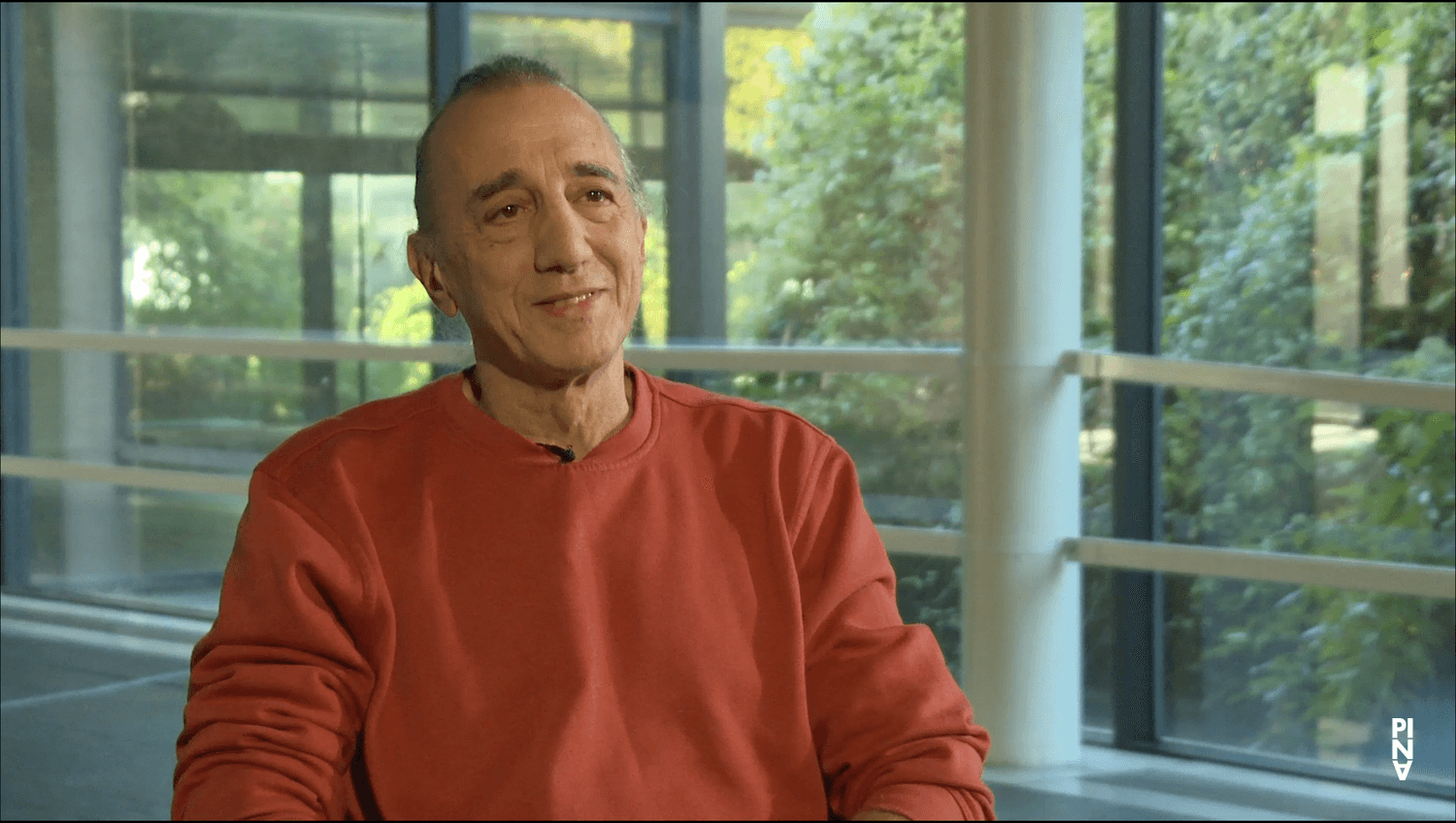

Dominique Mercy:

PIna was invited for for three purpose: she was invited to teach, she was invited to reconstruct one of her pieces for Paul's company, and she was invited to dance. That's how I met Pina, I went to her classes and for me was another, like with Manuel, big discovery and recognition of of what dance can be, and what I felt so close to. I also saw the piece, I think it was Nachnull, it was just with women.

Ricardo Viviani:

Yes. She restaged the piece Nachnull in English After Zero, and she danced Phillips.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, she danced Phillips and for me it was like "WOW"

Ricardo Viviani:

There's very few people that actually experienced Pina teaching. Maybe you can talk about a little what you experienced?

Dominique Mercy:

It's so strange because she was most of the time complaining, almost crying that she wasn't able to reach, or it wasn't good, or people didn't like it. I understand this so much.

Dominique Mercy:

For me, it was a mixture of knowing the person a bit better, by being on her side in daily life, a natural way to understand. It was the first time I was in a class with this technique coming from Jooss, Laban, Leeder, and of course Jean Cébron and Hans Züllig which Pina came from. All those exercises that I afterwards recognized, and for me, it was a big discovery. So it was a mixture of enjoying the class because of Pina, and the way she moved, the way she was showing it, of way it meant to be sharing this with me. Yeah.

Dominique Mercy:

All those movements, this notion of space, this round and strange movement, which I never had to cope with, which I felt very much at home. I liked it very much, you know? It's funny because I cannot remember so well, how she particularly was teaching. I remember some of the movement that she was teaching, I just liked it, you know? I just liked it.

Ricardo Viviani:

There's one beautiful thing that Paul Sanasardo said in his interview that I did with him a few years ago: that there is a very strong bond that's formed when two people dance together, and that's a very strong bond. It's a difficult thing to articulate, it just establishes itself. That connection is very strong.

Chapitre 3.3

Nachnull and PhilipsRicardo Viviani:

The piece that she did was called Nachnull. She was restaging to completely new dancers, the dancers of Paul Sanasardo's company. Do you remember some of that?

Dominique Mercy:

I remember some of the movements, especially that one were going very far back. I didn't see much of the rehearsals beacause they were rehearsing with just with the women of the company. I saw the performance, but what I remember very strongly was she was again ... not complaining ... – the dancers were complaining because it was it was so demanding physically, because she had those movements which were really extreme; like in Phillips, those things which we took over for some of the early choreography which she made with us here in Wuppertal, which I love: those all those crooked and contorted. I remember there was a lot of back hurting and complaining from dancers because they were not used to, and they didn't know how to cope with it. And Pina, like for the teaching, being sad that she had the feeling that people didn't like her, or it didn't work, or she didn't know how to make them go forward and things like that.

Ricardo Viviani:

And then the piece that you did with Manuel: Sextetrahedron, which I think I did learn afterwards, I worked with Manuel Alum ten years later, 15 years later. Do you have memories of that?

Dominique Mercy:

I have memory of the set of Sextetrahedron those sort of pyramidal structures. Mostly I remember this sort of diagonal to enter with a rond de jambe e coupè 'tic tic tic'. I don't remember which music was that. I have the program somewhere. I know it's all there, but that's vaguely the sets and this diagonal entering 'tun tun tun tun'. I think I have a tape from it.

Dominique Mercy:

No, after the summer I came back because I had to be in Angers, since the company moved into Angers, we did three years in Amiens, and I did two seasons in Angers. So I came back and since I had this very strong and incredible experience in the States, with Manuel and Pina. But not only that, also all the surrounding, the campus, Jacob's Pillow and Connecticut College, there was all those things. For me as a young dancer it was such an incredible, beautiful experience, which I just had. Artistically I felt that I cannot stay anymore in this company. I already felt a little bit like this, but I wasn't sure. But for me, this summer in the States with Manuel and Pina was clearly a turning point. So, when I came back, the first thing I did before it would be to late not to be engaged for another season, I quit. I quit the company. I wanted to be sure that I didn't have to make another season, whatever happened. I didn't know what was going to happen. For me, it was just important to open a door to something different in France or wherever. Which was not to the taste of Françoise Adret. Few years later she said that first she was the one who took me out of Bordeaux, and then I was the one leaving her, and she didn't appreciate so much. But she understood, few years later we met again, and we had the most beautiful rencounter and relation, until she passed away. I did quit, and I didn't look for anything specific. Then I received this letter. I always thought it's a letter from Pina, but I still haven't found it. So I don't know if it was Pina or Malou who wrote to me.

Dominique Mercy:

I think Pina wrote to me: 'do you remember this project?' When I was in Saratoga, one day in the kitchen, she asked me: 'would you like to work with me?' And I said, 'Of course.' I did like her, I did like the the the the materials she was dealing with, and what was happening with her, and I said, yes, of course. I mean, she just told me. 'there might be something on the way', but she didn't want to talk about, because dancers or artists don't like to talk about projects before they're not decided and fixed, a sort of superstition. So she wrote to me and reminded me: 'you remember you told me that you would like to work with me. So the project it's taking place, and Malou said already yes, she would come. Would you like to come to Wuppertal? I'm starting a new company.' I finished the season, I packed my suitcase, and I went on my way to Wuppertal. This was August 1973.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes, there was. We probably did parallel work, because we did work. ... She was still living, for a short while in a place from a family nearby the Zoo in Wuppertal. What was the name of the street? Zur Waldesruh! A very residential section of Wuppertal above the Zoo, wonderful villas. She was living in the house of one of the important textiles families in Wuppertal. I said this because I remember spending time with Agnes de Mille in a flat in that house. So we probably started quite soon working with Rodeo.

Ricardo Viviani:

As far as the documents, her assistant started to work and she came later into the process.

Dominique Mercy:

We started to work with the assistant, but I don't know if she came so late. I can't remember. Whatever, she was there. She came and she was a wonderful, funny woman. This little woman was very nice. I think we were probably splitting the rehearsal in different schedule. We were also working on The Green Table with Anna Markard and also Kurt Jooss who came also for rehearsal, working with us.

Chapitre 4.3

Operas in WuppertalRicardo Viviani:

The company was, at that point, the city theater company. With verything that's supposed to be there. And the format of a three ballet evening was also sort of a established dance program.

Dominique Mercy:

I had left the Ballet Théâtre Contemporaine because it was only focusing on dance evenings, no opera, operetta. I had the feeling, and Malou was well, coming on her side in Marseilles, and my site in Bordeaux, we had the same sort of education, or career beginning being involved in opera and operetta and all those things. When we came there, which was not on the agreement of everybody in the company, Pina made sure that we didn't have to appear in any of the ballets of the opera or operetta. It was a sort of a privilege, but that was one of the conditions, because that's the way I felt at that time. But it could have been interesting. Pina didn't do much of those things, she always gave it to Hans Pop.

Chapitre 4.4

FritzRicardo Viviani:

Young choreographer, Pina Bausch 33 at that point, doing a big debut piece, next to two big names: Agnes de Mille and kurt Jooss, somehow honoring our own tradition. Jooss and Agnes de Mille, and Anthony Tudor in the English side. She all of a sudden opened the floodgates of creativity: Why? What she was able to do? What she could do? What you wanted to do? And she was on record saying that she set out to do Fritz, as with some kind of 'Märchen', some kind of fairy tale.

Dominique Mercy:

Which I always forget the title of this 'Märchen'.

Ricardo Viviani:

We'll come back to that. Do you remember the sort of creative thinking and process, and how that creation come to be?

Dominique Mercy:

For me it's on a different level. One thing was clear: it was about this sad, struggling family which was made out of this couple, the son and the grandmother. So there were this one, two, three, four family members opening the piece. This grey and somber and not very happy surroundings. At one point that this little boy suddenly, being not loved enough or left alone, is building his own world. At that time she didn't work with questions, she worked quite traditionally, in that she was constructing after a certain pattern. So it was clear there was this story coming up with this family, this little boy having his own fantasy, which was then sort of translated, by the way that at one point the room will be much lighter and much bigger. The walls will open up and the grandmother would be gigantic somehow, and you will have all those figures, on one of the Mahler Symphony, this march, which has to do a bit with Beethoven's Seventh Symphony, a little bit slower. You have all those guests coming over and you have all those strange people: you have these Siamese twins with one jacket, you had this woman as a lamp, this figure in tights and big lips on the stomach [The Nose], and there was this woman with beard, and there was this woman with bald head and a wide dress. I was part of this because I was on this board with my head sticking out and just being pushed there. I was sort of a sick figure. I was in a nightshirt with a pillow, laying my whole head saying 'Mommy'. A lot of different persons, there would be interactions and a climax, then they will all go and disappear, and the family goes back to to what it was at the beginning. So there was this structure with which we were working and we worked on different parts. I remember we had quite a lot of rehearsing alone with this figure that I was doing in the piece. For me, it was the such a tremendous, incredible discovery. Not totally because the way of work was something I knew, about sharing steps and ideas, or she would provoke ideas. But what was underneath of it was, for me, the most beautiful thing: the feeling that it was about who I was – my sensitivity, my experience or my being. Like the coughing, we made this solo and everybody afterwards saw it. I had this, and I still have this coughing sometimes, and we made something out of it. And for me, this is what it was about: having a role, but it's connected directly with who you are. This is always, actually, the fact. I said this regularly when I'm asked, I never had the feeling during all my life that I was a puppet which was used and abused. You know, I always felt very much connected to all what I had to do. But this was was different with Pina, it was directly connected to something more essential about who I was. This was the most important. It was so organic, and it took place afterwards with the other pieces like, for instance in those two seasons, Iphigenie and Orpheus.

Ricardo Viviani:

I say a floodgate of ideas, because in Fritz it seems that she put so many ideas all of a sudden, things that she wanted to put into the pieces, there are so many figures. Also with the costumes, it's such a rich environment. Then when we look at the pieces that follow, it seems that she took a little step back and started to pace her ideas and how she was creating things.

Dominique Mercy:

I don't know if that is the case. What she always said and it was obvious that she always felt, that if she was too much prepared: going into the studio, she had the sensation she had to be prepared in terms of pleasing the dancers she was confronted to. Because sometimes it was not just working together, it was sometimes confrontation. That's what it was, sometimes, it was not always easy. That was one of the issues she was she dealing with, and the other one was that she realized that the more she went, the more she realized the richness, the possibility and the diversity of each one of us. And she wanted to find a way to let more place for this. That's why she eventually had this sort of stepping back, which was not really stepping back, but this took a little bit of time. I think that's one of the reasons how the work developed.

Chapitre 4.5

Iphigenie auf TaurisRicardo Viviani:

Thank you. That makes wonderful sense. What follows is Iphigenie.

Dominique Mercy:

There was Iphigenie, there was Orpheus, there was even in Sacre all these pieces with leading roles, or emerging roles. At one point she felt that for certain roles, those persons are adequate, or are the ones right for it, at the same time she felt that other one had other quality and how to make this pumping out ,or emerging. This came up and this was the time this emerged.

Ricardo Viviani:

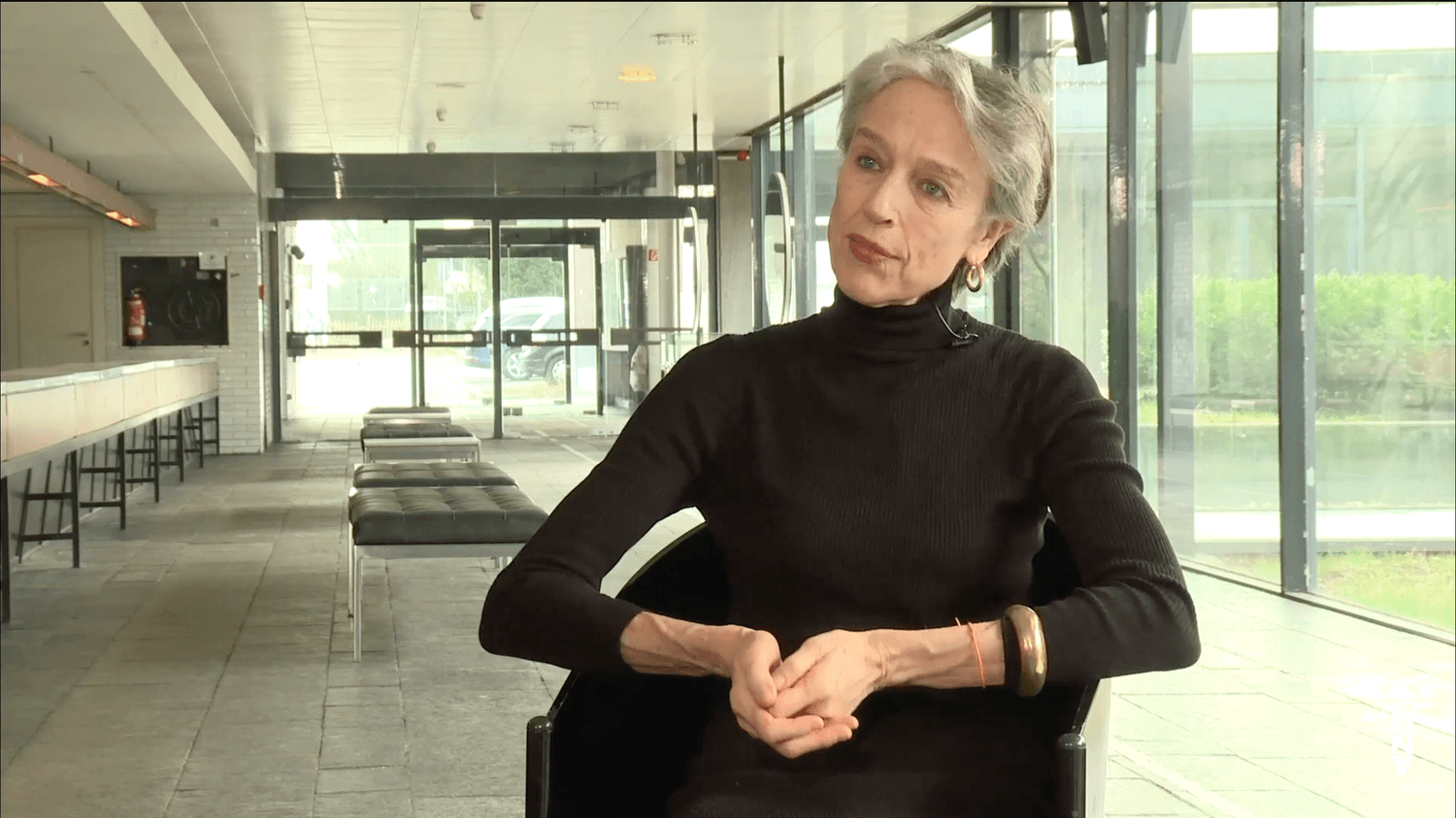

It also seems that Iphigenie was written for you and Malou in the sense of the success that it had.

Dominique Mercy:

I think it's based probably on many different things. It's based on the common sensibilities, or common reception to this sort of music, also to what it can provoke. And this confidence on daring and trying and touching different things. Where can you go, those moments which are sometimes not really movement or not really dancing, but they they are so important. I think it's really being on a common level. Which comes out of that you have a feeling that it's a bit mine. It's like a glove, it fits, you feel good with it.

Ricardo Viviani:

As far as movement in Iphigenie, was she still working into in the structured way that a choreographer comes and looks at the score, listens to the words and ...

Dominique Mercy:

Sure, she gave a lot of movement material, which mades us provoking things and proposing other things. Sometimes to make it possible, because you have an idea of a movement but you don't know if it's possible, if it's too complicated. That's what I mean by trying and daring, and sometimes comes something different out of it. It brings you in another possibility, for another person. There is so much. By reviving all those pieces, like Iphigenie, Orpheus you realize how much there is already in those pieces from Sacre from Café Müller, either as moments ideas or movements or. It's a lot of Pina in there, sure.

Ricardo Viviani:

I'm not sure if that's an innovation, that's why I ask you, if that's fine. While in Iphigenie where all the musicians, and all the singers are on the side. That's the whole staging that she makes, on the stage are the dancers. Did you experience that before? I'm trying to figure that out.

Dominique Mercy:

That was also for for us the first time being the singer and that it's such a beautiful experience. That's beautiful to be the music, being the voice, being that person who is singing and make it yours. It's such amazing experience and such grateful experience.

Ricardo Viviani:

That was the first season. Iphigenie have an enormous success, different from the first production.

Dominique Mercy:

This is was a strange paradox, because the audience in Wuppertal was used to ballet, to balletic style and ideas. Suddently to be confronted to even Rodeo and Green Table, but mostly to Fritz. The world was going upside down. Not only the house was half empty, but many left. Some of them stayed and were, since the beginning, big fans and had probably a very strong and lifetime experience, but most of them were just leaving the house, and not in a discrete way, slamming the doors. At the same time you had this another audience or a mixed audience, since it was more of an opera audience. There were the singers, there was the music, a combination of things that created an easier way to approach, to receive the pieces as a language. Specially in Fritz, which was really strange. It was so strange to have this two different poles: on one side the audience which was rejecting us – Pina received really hard letters, menacing letters; and on the other side, this tremendous success with the opera Iphigenie. So it was very strange, and interesting.

Chapitre 4.6

Wuppertal under Arno WüstenhöferRicardo Viviani:

I must say that the Wuppertaler Opera was, at that time, a very forward looking company. The repertory was very modern with Hans-Werner Henze and ...

Dominique Mercy:

Absolutely. I remember Pina was in this ... who was the composer of Yvonne? [Boris Blacher] Pina was invited by this wonderful opera director at that time, Kurt Horres was his name. A small but very active, energetic and really forward looking person. And there was this 'Intendant' [General Director] who was a big part of helping Pina to have confidence and keep struggling, which was Arno Wüstenhöfer.

Ricardo Viviani:

Do you remember her performance in Yvonne? What do you remember, can you tell us?

Dominique Mercy:

I loved this. It was a mute role. And she was beautiful with this bloomy simple dress from the fourties. She was fantastic.

Dominique Mercy:

He started quite early filming Pina's work. I mean he started with Fritz, but as far as I remember, there is not a complete version of Fritz. There are some different parts with different casts. But he did start the filming of the pieces with Iphigenie, then he always filmed everything. When he wasn't filming then Hans Pop was filming.

Ricardo Viviani:

Was Rolf around Fritz? Are some of the costume ideas from him?

Dominique Mercy:

He was there, helping Pina on one way or the other since the beginning, that's for sure. And I thought I thought that all the costumes from Fritz and the scenery were made by Markard, but if I remember well, at least one of the figures in Fritz, the one with the lips – I saw some drawings from Rolf for this, I think this idea probably came from him. I didn't realize at the beginning, because most of the costume ideas came from Markard.

Ricardo Viviani:

I'm not even sure if it's Markard, yes, I guess it is. That's true, absolutely right.

Dominique Mercy:

That's the only thing he did with Pina. And his [wife] Anna was the assistant of Kurt Jooss, her father for The Green Table. I think that's the only thing he did together with Pina [for the Tanztheater]. I don't remember who did the stage sets from Iphigenie but I know that Rolf did the leather coat for Thoas, that was also his idea. The second thing he did was Orpheus. His very first complete production together with Pina was Orpheus.

Chapitre 5.1

"Adagio"Ricardo Viviani:

There is Zwei Krawatten in between, then there's the three-piece evening with Ich bring dich um die Ecke..., Adagio and Gross-Stadt. Which is quite amazing, as I was looking at Adagio, and Mahler was very popular as has music for dance at that time.

Dominique Mercy:

For me it was a big discovery Mahler. I didn't know it at that time and I will just like wowed.

Ricardo Viviani:

And you are very central in that piece, actually, you're sitting on the bed ...

Dominique Mercy:

Well, we all have our different parts. I don't know if I am very central, but ...

Ricardo Viviani:

What I find amazing is that she actually dress everybody as regular people. They're all doing the Mahler piece, doing the choreography. Then you see her aesthetics of bringing the everyday person into this choreographer, and it was never done again.

Chapitre 5.2

Ich bringe dich um die Ecke...Dominique Mercy:

Mahler? I don't think we ever did a revival. Never, I think. Ich bringe dich um die Ecke... either, we did once in the foyer in the Schauspielhaus for a certain occasion. But after that season, we never did it again.

Ricardo Viviani:

There's this whole environment of people relating to each other and you really see that there's something else that she brings.

Dominique Mercy:

We had a really nice time. I wouldn't be able to reconstruct it in my memory, but I remember we had a very nice time and also because there was no music. We all either sang or played an instrument, and that was the music. Old songs: Taboo, Man tanzt Foxtrot, Es geht die Lou Lila, there was all those different songs and we were singing them, so it was a lot of fun. And having those, those crazy songs ... Der Onkel Doktor hat gesagt, ich darf nicht ...

Ricardo Viviani:

The sets with these white tables, that becomes different things ...

Dominique Mercy:

Constructing and disconstructing the environment with the tables was really fun, also having those strange figures there.

Ricardo Viviani:

Also, she asked Kurt Jooss to bring one of his pieces together.

Dominique Mercy:

Yes Gross-Stadt.

Ricardo Viviani:

Do you remember? Did you dance in it?

Dominique Mercy:

I didn't connect so too much to it. I was really interested, and I liked very much to work on The Green Table, but I didn't connect so much to Gross-Stadt. This may be a bit exaggerated, and she'd probably wouldn't like me to say that, but I was a little bit bored. It didn't catch my interest as strongly as The Green Table did. I remember this figure from Hans Züllig playing the young man. I don't remember if he came and worked with Michael Diekamp when we did this. I was not so much spiritually and emotionally involved in it.

Chapitre 5.3

Orpheus und EurydikeRicardo Viviani:

Orpheus, which is the second evening in the second season, is again an opera, but done in a different way. Right now, we are doing a the revival of that piece for the Tanztheater Wuppertal, for the record. What was the new development there? Now we have a different relationship with the singers. Tell us a little about that.

Dominique Mercy:

One of the first things I remember about Orpheus is with Pina in the first studio apartment, which we have in Zur Waldesruh by the Zoo there. Since they have to program it early enough, it was probably shortly after Iphigenie, in that same season. Pina came to spend a little bit of time in our place, and she told me: "We have the possibility, they asked me if we could do Orpheus. What do you think?" And I said: "Oh Pina, right now!" Because I had a very special connection to that opera because we had done it in Bordeaux, as I was a young member of the company, either the second or the third season. It was done in a more traditional way, like it was done in the opera and there was the ballet which takes place, traditionally. So there was the Champs-Elysees, there was the Furies, all those things. But with the singers in a more traditional way of staging it. The woman singing Orpheus was one of my favorite opera singers Rita Gorr. The role of Orpheus was one of her most important roles and I loved her. She came a few times to the studio as we were choreographing, creating the ballet for the hell and all those places where she has to sing. She would sit, it was probably a moment where I didn't have to dance, so I was sitting there in the studio, and there was a little podium for the teacher, that high. She was sitting on the chair and singing and I was sitting just beside her. It's something I will never forget, in your studio one of your favorite opera singers just singing beside you and this wonderful music. I had this really strong connection to this opera, I knew it from the beginning to the end. In opposite to the Italian version, which is quite different, the German version and the French version are quite similar. When I heard that we had the possibility to do Orpheus and I would be eventually the Orpheus on top of it, it was like "Yes Pina let's do it." She was quite happy for my reaction, and then we did it. And it was very clear from the beginning that the singer would be present. There was some something which was there from the beginning.

Dominique Mercy:

It's one of the big presents, I consider it as a present and as a milestone in my in my way together with Pina. This belongs as a very special thing.

Ricardo Viviani:

It was dormant. It didn't come back. It was played one season, two seasons, and then in 1990. It came back. Did that surprise you, that Pina was going back to something of the early repertoire?

Dominique Mercy:

Well, I think it did surprise everybody, but the thing is ... In French we say concours de circonstance

Chapitre 5.4

Restaging Iphigenie aud TaurisDominique Mercy:

Then we have to go back to Iphigenie, because it was an anniversary – I don't remember if it was the death or the birth from Gluck. And one person at the Goethe Institut, probably together with Thomas Erdos, if I don't mix everything, because sometimes memory plays with one. It was at that occasion that she was asked to perform in Paris with Iphigenie. She was sort of attracted to the idea, but she was not sure, and when she told us about this, we didn't know. But before we do it in Paris, we have to do it Wuppertal. I don't remember the background of the decision and the timing. But we were not sure at all, we didn't know if we would remember, and how do we would react to it? Do we still agree with it, did it get old, did it stand the time passing by? What would be our reaction in relation to it? Thanks God, we had all those tapes which Rolf had filmed, very ghostly ones, with the old tech in which you see the ghost going through the picture, like Sternschnuppe [sooting stars]. With the help of this, and the incredible memory of Pina by doing it. We always compared it to opening a shelf and by looking you say: "Oh yes, this! Oh yes that", and all the pieces of the puzzle take their place again. So, we realized that that everything was sort of there, even after about 17 years passed since we last done it. That we remembered, that we had fun to do it again, that we could do it again, even after 17 years, that the technical, the physicality, the capacity was still there. Also because Pina said: "I do it, but I do it with you". We weren't sure, neither Malou nor I, how it would be then, and Ed Kortlandt of course in Iphigenie. We had fun, and then we had the feeling that it didn't take a wrinkle. There was eventually a time stamp, but also not, that the language, that the aesthetic was ... When you see some of the new staging for some opera nowadays, you think: "Wait a minute. We've been doing this like sort of 40 years ago. So just okay, sit back." So we said, let's do it, and we had a lot of fun, it was beautiful to do this again. It it was like a second youth for all of us, to be able to take on those clothes again. And what happened was that the logical follow up was to do Orpheus. I don't remember if it was also because the opera, Brigitte Lefèvre invited us to do Orpheus, that we restaged it, or if it was just in the continuity of restaging Iphigenie. The last time we did it was in Genova in Italy in 1996. That's the very last time we did it, and we did the revival with the Paris Opera Ballet.

Ricardo Viviani:

And recently in Dresden.

Dominique Mercy:

Recently in Dresden, two or three years ago. She was very happy with the how we did it in Paris. She knew she wouldn't do it again because for Pina, the way she approached the idea of working and restaging, she's really demanding. Rightly so, more demanding than most of the other people in the dance world. But there is a reason in this, it pays somehow. She knew she wouldn't have, and want to take the time to really work on it with with the group, and she wasn't sure. Also Iphigenie we never did as much as Orpheus. After the revival of Iphigenie it was clear for me – I remember sitting in the office with Pina I said "I think it's wonderful to do Iphigenie, but either you give me another costumes or I sing. My time is done with Iphigenie." The body sort of changes, even if you have the capacity, the physicality, but the body shows a little bit differently. "Either you give me a toga together, and I do it in another costume, or we will have to find somebody else." And then we did work with Pau and had a beautiful revival of it. But Orpheus was a bit more complicated because it's quite technically quite demanding, she wasn't sure if she would have the people for it, and she certainly didn't have the time or didn't want to take the time she thought she needed for it, to bring it back into the company. Also, because it's complicated, as you'll say it, with the orchestra, the opera singers and all these things. That's why she was very happy with Paris, and there was probably a three or four years contract, so we had the possibility to redo it again a few times, with her and then without her, unfortunately. That's why I was always skeptical about the fact to redo it with the company. But this is something which I have to cope with.

Voir aussi

Mentions légales

Tous les contenus de ce site web sont protégés par des droits d'auteur. Toute utilisation sans accord écrit préalable du détenteur des droits d'auteur n'est pas autorisée et peut faire l'objet de poursuites judiciaires. Veuillez utiliser notre formulaire de contact pour toute demande d'utilisation.

Si, malgré des recherches approfondies, le détenteur des droits d'auteur du matériel source utilisé ici n'a pas été identifié et que l'autorisation de publication n'a pas été demandée, veuillez nous en informer par écrit.