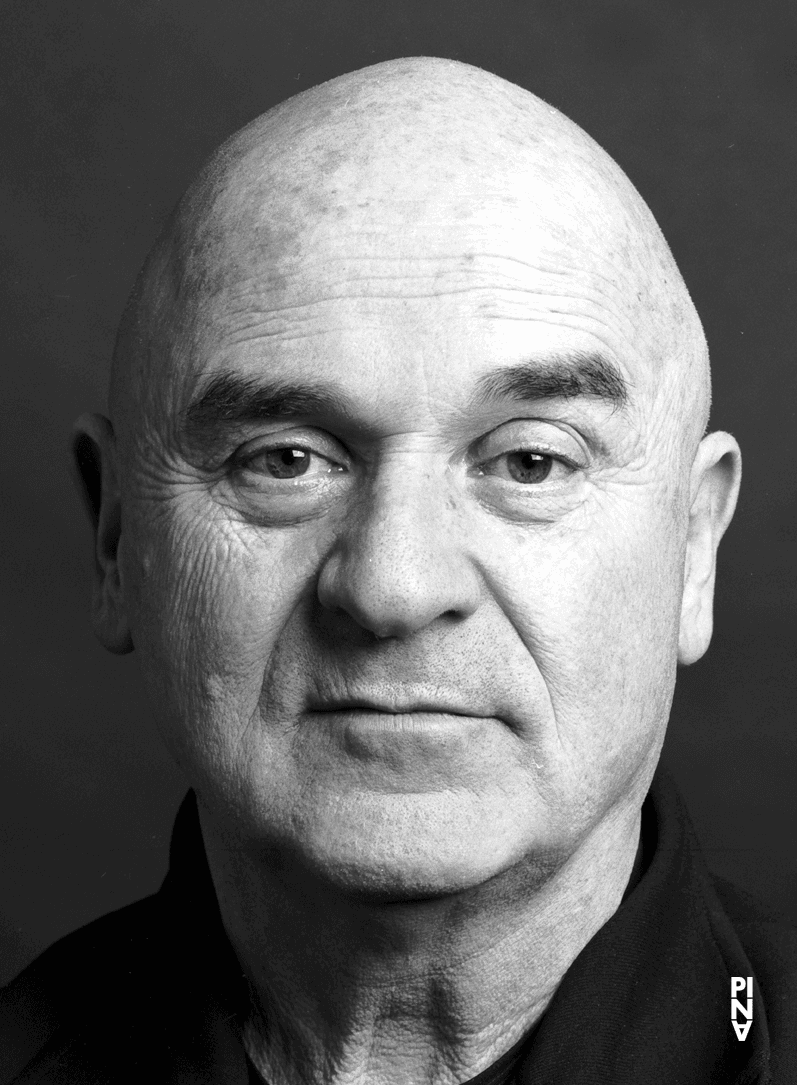

Peter Pabst: Peter on Pina

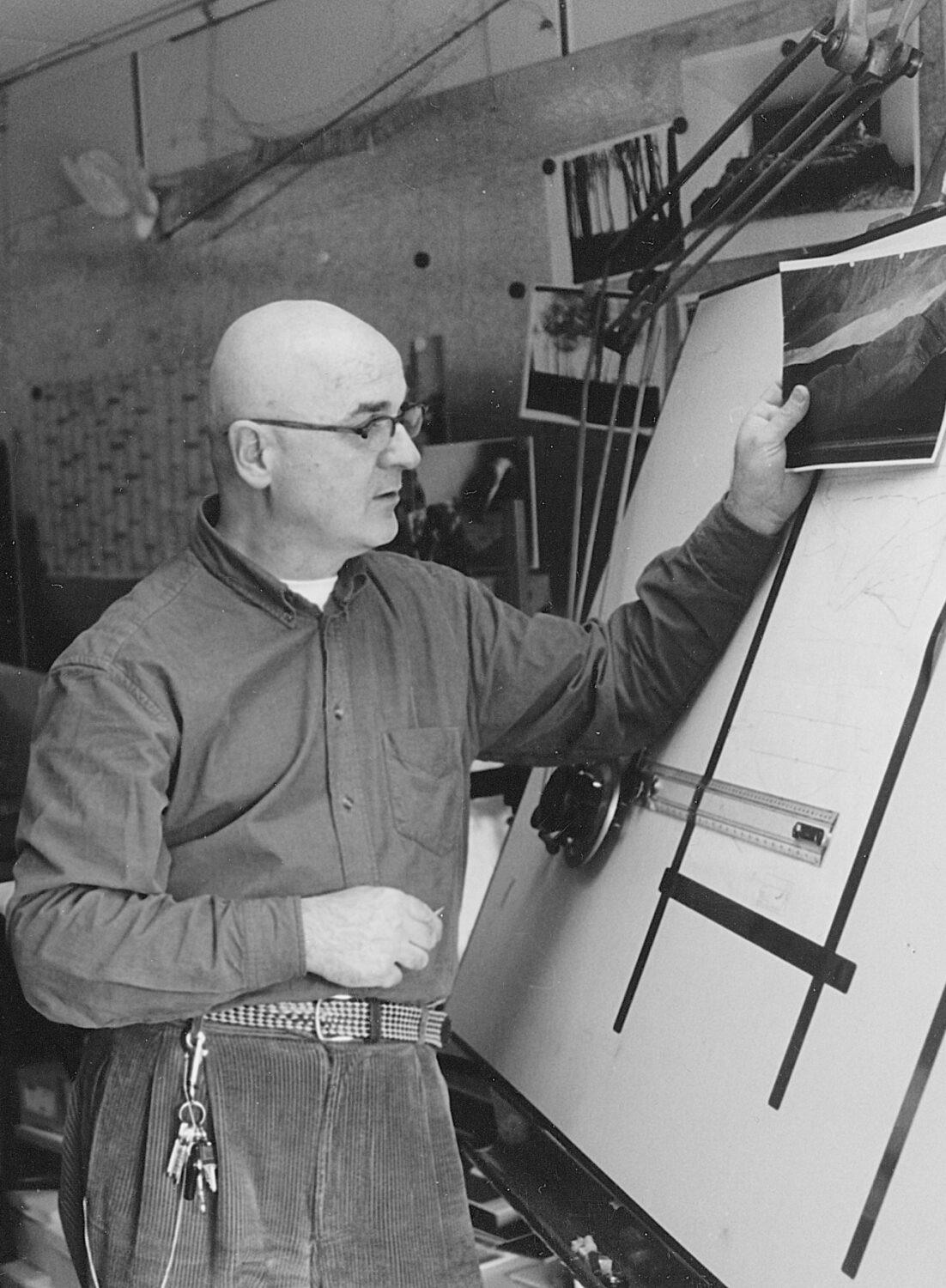

In the 2020 annual issue of Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, Peter Pabst has written about his work with Pina Bausch. He designed many stage sets for Pina Bausch's pieces. They worked creatively together for many years. In his text, he recalls their collaboration.

Peter Pabst and Pina Bausch in Hong Kong during an intermission.

Writing is hard, writing about me even harder, and writing about Pina Bausch is almost impossible - at least for me!

I have been incredibly fortunate that Pina Bausch allowed me to enter into a close, almost symbiotic, artistic partnership with her for more than 29 years.

Her dancers are in my heart and many of her collaborators are my friends. In short: It is my family.

For all the external constraints, working with Pina was the most freeing experience I have ever had.

When I think of her work with the Tanztheater, three words come to mind:

Freedom, risk, and - almost a contradiction - trust.

Freedom was so important to Pina; for herself and for everybody around her.

To liberate art over and over again, freeing it from its narrow interpretations, definitions, rules and regulations.

To experience art freely, exploring and expanding its realms and outer boundaries.

Freedom, too, for her dancers.

For their imagination, souls, and of course their art: the dance. They were allowed to grow wings - while having both feet firmly on the ground.

Of course it is always risky to break new ground.

Dismantling old forms means having to find new ones.

There is risk in leaving a well-trodden path just because I have seen something on the way that has surprised me. I may easily get lost.

Pina was always prepared to take this risk.

The word “trust” seems like a contradiction.

If I am scared, I will not take risks, and I can only feel free when I trust.

When Pina rehearsed for a new piece, everything had to be possible.

The dancers had to feel free enough to be able to show every idea - in word or in movement - immediately and without hesitation, trusting that nobody would judge or belittle them for it.

This is why no visitors were ever allowed to attend Pina’s rehearsals.

They were held in the strictest confidence.

No idea was too small to be taken seriously by Pina, who always considered how it might fit into the new piece.

She was alert to everything.

But there was also another kind of trust:

The dancers could absolutely trust that Pina - and I, as the same was true for my work - would never do anything to damage their dancing or allow it to be impaired in any way. Difficult - yes; damage - no.

This was a fundamental law.

Pina’s pieces: It is a large repertoire. 40 pieces by Pina Bausch.

And our collaboration? Almost 30 years! I designed 26 stage sets for Pina. What was so special about that?

30 years, huge struggles, profound desperation, but over the years we also always kept the most beautiful surprises in store for each other. I see it as a declaration of love.

Never during all this time did we try to burden the other with the weight of our own insecurities.

We frequently argued, sometimes in anger. But we never lost our respect for each other. Pina was very respectful and I also tried to be respectful towards her.

This too, was special in our relationship: We were very different, in some ways as different as fire and water.

Nevertheless, when we were in Beijing and I was answering a question from a Chinese artist about how we talk to each other when we are working, she interrupted me and said: “My dear, we have never needed to talk much at all!” Many contradictions and great harmony, especially when we were working. On the cover of my book “PETER FOR PINA” she smiles like the Mona Lisa.

Pina always responded creatively to difficulties. The most beautiful example I can remember was very early on, in December 1982.

Nelken (Carnations) was just about to be “born”. The set was being built for the very first time. Everybody knew that there would be carnations, but now it was something else: an entire field of 8000 pink carnations. It glowed under the stage lights in such immaculate beauty that even I was dumbfounded. Speechlessness all round. Within minutes the news had made the rounds, the theatre stopped working and everyone came to the stage to see the miracle.

I was standing next to Pina and suddenly I had a terrible realisation: These 8000 beauties would be trampled on and crushed by the dancers. Pina said simply and very calmly: “We can add a scene where the dancers prop the carnations back up. They will comfort the carnations.” I loved her for saying that, loved her for the next 28 years.

We didn’t end up doing the scene, because watching the slow destruction of their proud beauty was even more exciting.

The carnations were usually “comforted” the morning after the performance by a team of technicians and volunteers. Unforgotten in Amsterdam: six volunteers sitting by the canal in front of the Theater Carré in the morning in blazing sunshine. They were frightening-looking men: tattoos stretching across huge muscles, broken noses, missing teeth - to see them gently straightening out thousands of pink carnations with so much tenderness was a dream for Pina!

Pina had no real inclination to judge things or achievements. She was very modest, except in the demands she made on herself, which were excessive. She never talked much about art. The fact that only the very best was good enough was self-evident, not even worth talking about. I often saw her lying on the floor between two rows of seats in the theatre, totally exhausted. And recently I also found a photograph of myself, sleeping on a row of seats in the Schauspielhaus. I had specifically chosen the folding seats.

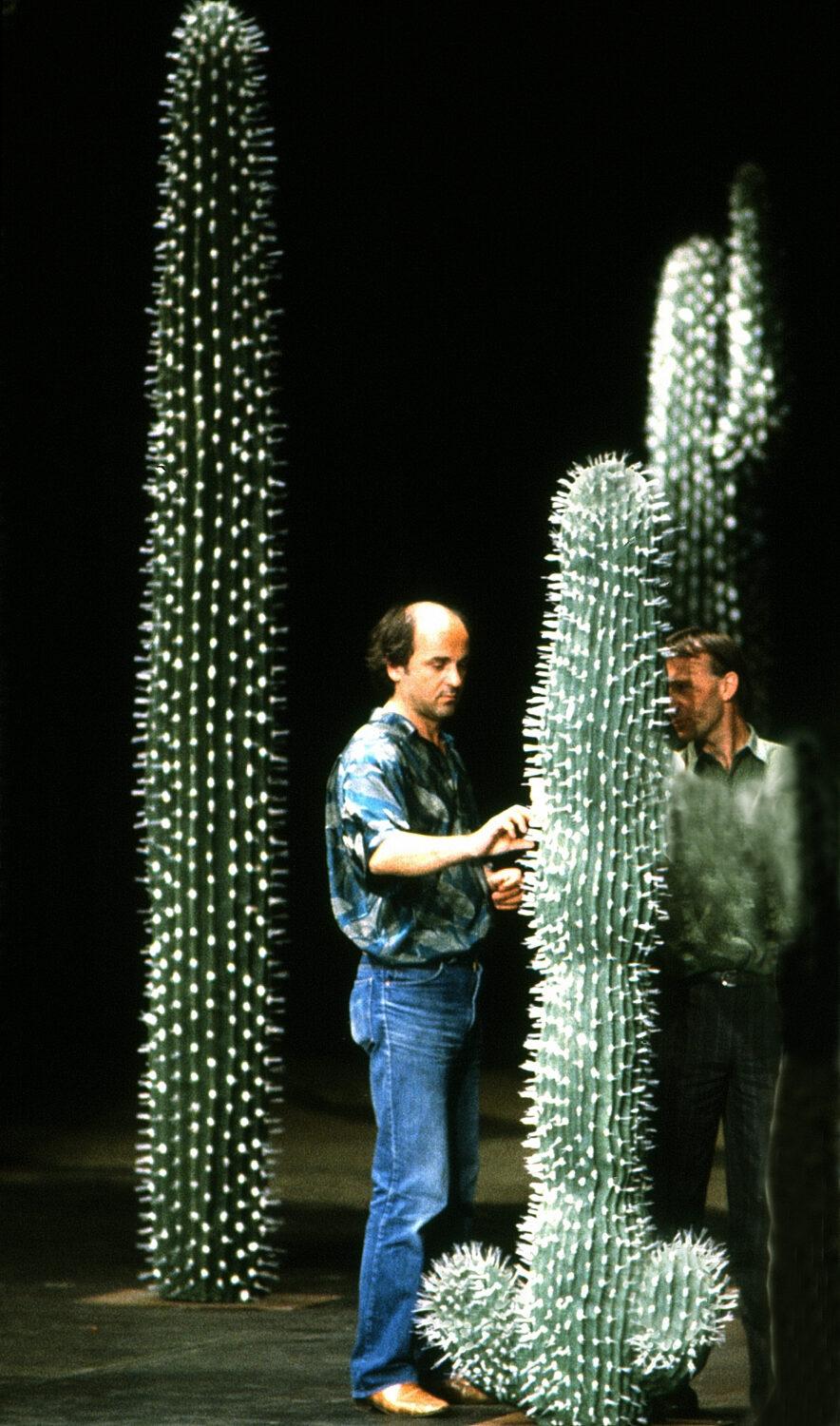

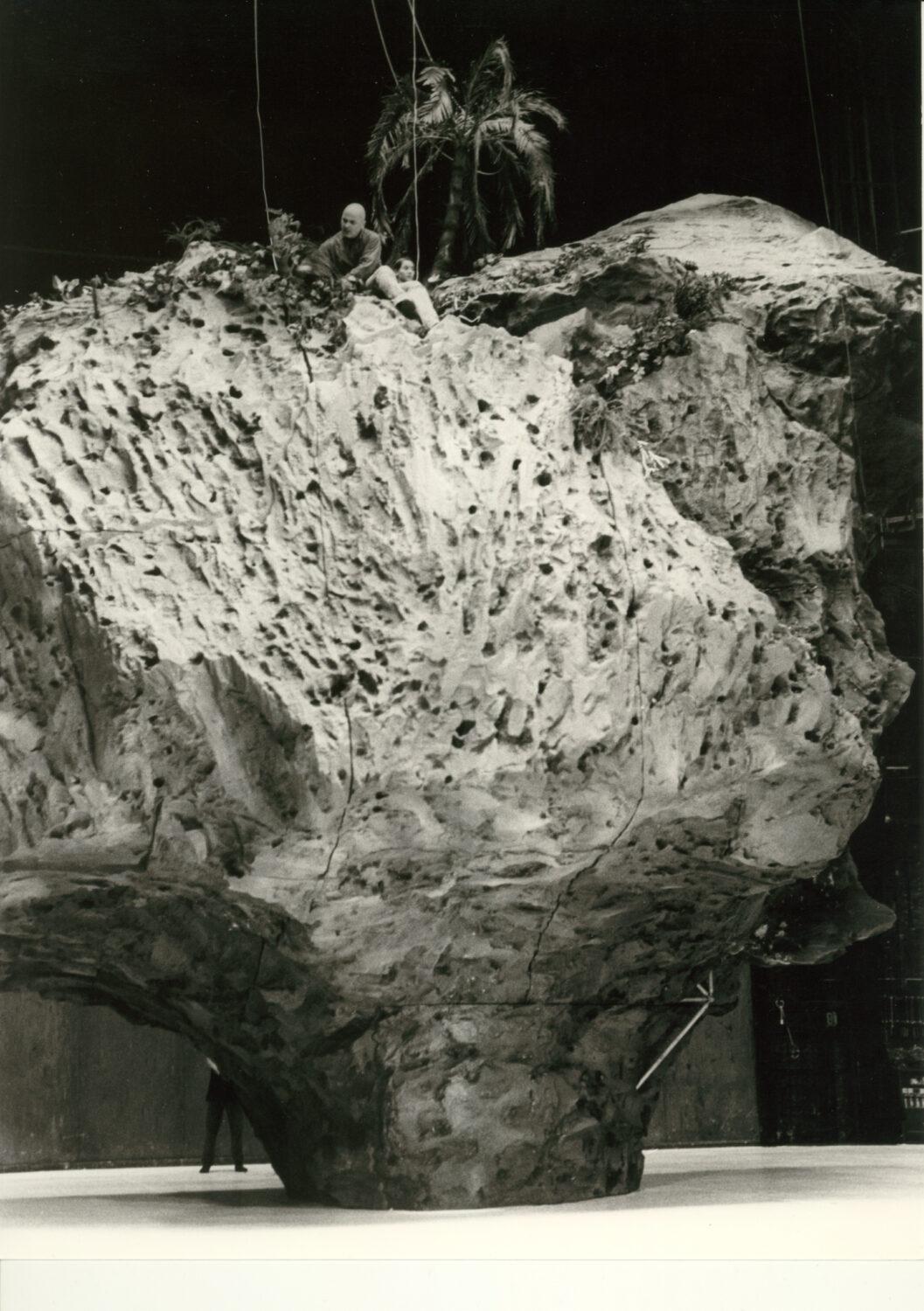

But it was never enough. When I showed her the designs for a new set, she would immediately ask: “What else can it do?”, or: “Does this always have to be there?” For example the pond in Nefés or the mountain of flowers in Der Fensterputzer (The Window Washer). I believed it was not my job to say no, so I always promised her the earth without actually knowing how to achieve it. In Wiesenland, for example, I told her that we would be able to turn the huge moss wall around, hanging it from the ceiling. The dancers would then be able to fall from the wall onto the stage. I was lucky that she did not go for this idea, because otherwise I would have probably been asked to leave the Tanztheater in 2000.

Infinite energy: Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehört (On the Mountain a Cry was heard) is one of the pieces where Pina was relentless in her demands on the dancers. It was so full of aggressive energy, so unyielding, that it was frightening. The theatre’s doctor was called after almost every performance and in the end there was just pure exhaustion. From everyone, including the audience. Pina knew that energy, when expended in excess, develops its own power and special quality. This desire to generate tremendous energy in herself and her dancers never left her, until her own end.

In her final piece there was a question from the dancers, asking if we might leave the crack in the stage floor open during the final scenes. Pina was like a rock, refusing to even entertain the idea. “You know”, she said to me, “I’m sure they can deal with a crack in the floor and would not injure themselves. But I want them to dance the final scenes all out and incredibly fast, without holding back at all. So I don’t want anything in their heads that might slow them down.” This was no more than three weeks before her death, when she could barely even sit anymore. It is an image that haunts me to this day. Pina Bausch’s 40 beautiful pieces were created out of this unrelenting spirit. We should not forget that.

Recently I was asked to look back on my time with Pina and whether I miss working with her.

I miss Pina.

But I like remembering her and I think it is amazing that our time together even happened. It is alive in my mind and in my heart. It was a privileged, precious, wonderful personal and professional relationship.

We encouraged each other to have courage!

27th April 2019, PP