Interview with Robert Sturm, 20/9/2018

Robert Sturm came to Tanztheater Wuppertal during the creation period of Wiesenland. His interview is rich in details about this period. He comes from a spoken theatre background, but dance was always present in his life thanks to his Hungarian step mother, a ballet dancer. The discovery of the work, methods of creation, and repertoire maintenance of Pina Bausch make a lasting impression on his way of working. He became a very close associate of Pina Bausch in daily routines of the company. Through the description of his different attributions and work-titles, one learns about the company organisation under the leadership of Pina Bausch. In the last part of his interview Robert Sturm talks about his period as a co-artistic director of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch.

The interview was conducted in German and is available in English translation.

| Interviewee | Robert Sturm |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20180920_83_0001

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

Theater familyRicardo Viviani:

Perhaps you could describe your background – in terms of theatre and dance.

Robert Sturm:

I grew up with theatre really, because both my parents worked in theatre. My father was an actor, so was my mother, and when I was five my father married a Hungarian ballet dancer. So dance was part of my life, even then, a bit. I always sat under the piano during training – things like that. That was in Gera, which was also where I first saw Café Müller and Rite of Spring, in 1987, in what was then the GDR. I was working in theatre then too. I had finished school, and done military service, slightly shortened, and I actually wanted to be a director’s assistant at the theatre, which the personnel department at the time there blocked because of my political views – they told me that openly. But because they’d known me at the theatre there since I was a child, they said they wouldn’t let me starve and hid me away in the sound department. Which was alright, as the equipment was ancient and very easy to learn – otherwise I have no clue about technology. In retrospect I’m very happy about it, because I got to work with all the genres: theatre, opera, dance, concerts – the whole spectrum. But only in retrospect. At the time of course I was angry I couldn’t work on plays from the start.

Chapter 1.2

First contact with Pina BauschRobert Sturm:

Yes, so then in 1987 Pina Bausch came. I wasn’t allowed to work on the day itself, because of the West-Germany contact. But I was allowed into the performance with a ticket and of course I was fascinated by both works, Café Müller and Rite of Spring. And someone told me there would be a nice party afterwards in the Interhotel, where I think the company must have been staying, but I was denied entry by the Stasi. If someone had told me then that one day I’d be sitting here describing my work with Pina Bausch, I’d have been the last to believe it. So that was my very first encounter. Before that I’d heard the name Pina Bausch but couldn’t have told you anything about her work, or what was different about the dancing. I’d had no involvement with it. But this evening was of course very, how can I put it, surprising. It opened up new worlds, new ideas about what dance can be, and theatre in general.

Chapter 1.3

Moving to CologneRobert Sturm:

Then in early 1989, less than a year before the wall fell, I left for West Germany, lived in Braunschweig first then started studying theatre, film and TV studies in Cologne. Of course I went to Wuppertal from time to time, to see other shows by the Tanztheater Wuppertal. But it never occurred to me to apply for a job there because I was too involved with acting, in theatre as well as film, to get into dance – Pina Bausch was always first and foremost a choreographer to me, even though her works were often a real mixture. But I watched them with great interest, and the crucial encounter came when I…

Chapter 2.1

Moving to BudapestRobert Sturm:

The backstory was that in 1993 I broke off my studies in Cologne to join a director from Munich who’d been invited to the Budapest National Theatre for two productions. He knew I’d spoken Hungarian since my childhood, thanks to my stepmother, and asked if I fancied coming, so he wasn’t on his own in a foreign place. And I did it, and then stayed on in Budapest. A new theatre was being founded at the time. They asked if I wanted to join the team as dramaturg and director’s assistant. And I did, and anyway – I also started doing my own shows – anyway I ended up there for six years, till, in summer 1999, I had a call from the Hungarian Theatre Institute saying Pina Bausch was coming to Budapest at the end of the summer with her company, or rather with the future cast of a piece, so part of the company, to do research and development – for three whole weeks I think it was, not just two. Did I fancy accompanying her, because she didn’t want an interpreter or tourist guide, she wanted people from the theatre, who could hazard a better guess what kind of things about Budapest and Hungary might be interesting for Pina, which impressions. Obviously I agreed, because it was still during my summer break, and so I got to know Pina and lots of members of the company. It was the research and development for Wiesenland. We travelled round Budapest together, out to the country, gathering impressions. The rehearsals took place then in the trafó, a contemporary dance centre. Yes, and suddenly the time was over, the three weeks, and then there were a couple of conversations, with Urs Kaufmann back then, and Matthias Burkert was involved. I thought, ‘what a pity it’s all over already, I won’t see it again till they come back to Budapest with the finished piece, or perhaps in Wuppertal, if I can get there.’ Then the idea was floated, that perhaps they could actually use another assistant. It would certainly do no harm. I don’t know why. I don’t know what the situation was previously there. It was certainly to do with the Hungarian factor in part, that I continued to work on that piece. That seems the most obvious reason. At any rate the plan was hatched that Matthias or Urs or someone – I forget who – would suggest to Pina it might be a nice idea if I stayed on. And then on the last evening in Budapest, I remember, we were in a dance hall, where Hungarian folk dancing was taught to anyone who felt like it: a totally accessible set-up. And the company were there too, and we talked for ages in the corner with Pina, a couple of hours for sure. She said she liked working with me, but of course she would have to think about it, as she always did, not decide too quickly. And we talked about all sorts, everything except theatre really. She didn’t want to know about my productions, or have me send her reviews or videos, or anything. We just chewed the fat and the result was that she just said, well I have a good feeling. She said she’d think about it and let me know. It took a while of course. I took a risk and pulled out of all my productions for that season. I was working freelance, so I was more or less free to do as I wished. I didn’t want to miss this chance to work on a Pina Bausch piece – in the event that Pina said ‘yes’. So eventually I got the call and then we arranged it so that whenever this piece was being rehearsed I was in Wuppertal – but only for this piece. I was there twice, I think, two weeks at a time, in autumn ’99. We signed a guest contract. Then there was a period with nothing, because Pina said/ At some point they had injuries from a tour, I think, and there were no rehearsals for new works, and I didn’t come. And after I’d been there the second time, planning to come back in January or something, my mobile rang, and they asked if I could possibly get the next flight to Wuppertal and help with all the pieces in the current season. Just be there, because Pina needed more help. Someone was ill and… It wasn’t the next flight, but I said I’d try for the day after next, and I did indeed fly the day after next to Wuppertal, without really knowing what to expect. So as soon as I got off the plane and arrived in Wuppertal in the theatre it was the dress rehearsal for Iphigenia, where I sat right next to Pina, without a clue what I was really meant to be doing here, because it was pure dance. (laughs) And the first problem was I didn’t even know the names for the movements and all that. But Marion Cito was there too, and we managed just fine. It got more interesting with the next pieces, where I started being part of the rehearsal process right from the start. I think Fensterputzer (Window Washer) was in my first season, the Kontakthof with senior citizens project, which I was at lots of the rehearsals for, with Beatrice still, without Pina at all quite often – but more to watch and support, though. I played the music and things like that. And just watched how it went. Yes, and so it became more and more established. I was part of Wiesenland anyway. Not the sole assistant, of course. Jan Minarik was still involved, and Irene Martinez and Marion Cito was there as ever.

Chapter 2.2

Contract in WuppertalRobert Sturm:

Yes and then it was the Wiesenland premiere and we went to Budapest. That was where it started, that I would start passing on Pina’s corrections to the dancers. Then… in spring 2000 there was talk about how really next season I ought to get back to doing my own work again. But then immediately we decided it was going well right now, the way we worked together, and I was helpful, and that till Pina had found the dancer assistants she was really looking for, I should stay on for a year or two, till everything had settled down. So it was extended. From summer 2000 I had permanent contract, my family moved to Wuppertal for a year or two. Yes, as I said, since…

That was in 2000. Now it’s 2018 and they’re all living here. We’ve got another family member. It didn’t happen quite as we were expecting. But yes, now we’re all here.

Chapter 2.3

Discovering the way of workRicardo Viviani:

Did you notice anything new yourself during the research phase in Budapest? Anything where you said, ‘that’s particularly interesting.’ In other words, did you make any new discoveries yourself?

Robert Sturm:

In part, sure. We did it together. Anna Lakos from the Theatre Institute was in charge, she… Thomas Erdos was also involved in the whole preparation and reflection. And Anna Lakos took the lead on production in a way. There were three of us: Kinga Keszthelyi and Anna Lengyel – was her name. They were both dramaturgs, or perhaps still students then, or they’d just finished college – I don’t recall exactly. There were three of us and we always considered together what might be interesting, and I can’t remember any more what might have come from me or… I also discovered some other exciting things I hadn’t known about in Budapest over the three weeks, I think. Because they were ideas from other people. We even went to the racecourse, and all sorts. Various things, in other words – in the countryside too. Villages – I’d never been anywhere like that. Visits to gypsies at home, visiting Roma families. (laughs)

Ricardo Viviani: Very exciting, all of it – discoveries.

Robert Sturm: For me of course, the most exciting thing wasn’t finding out about Hungary, after six years, but finding out about Pina and the company.

Chapter 3.1

Development of tasks and dutiesRicardo Viviani:

What was your job then, when you… Ok, you had to pass on corrections. All the productions have various people assisting – always described in different ways. What were you doing initially? I think your job description was ‘assistant’. [‘Mitarbeiter’ – a broad term often simply meaning ‘member of staff’ or ‘colleague’.]

Robert Sturm:

Yes but I think almost everyone was called that (laughs). Which of course also… You have to imagine, I’d come there, signed a contract and from that point on I was the one who did the rehearsals or made the corrections. I didn’t know most of the pieces at all. Luckily I had seen one of them that was currently in the schedule, otherwise it was a process of course. Mainly observing at first, helping out, helping Pina, sometimes noting down what she said, or sometimes when Jan wasn’t there, quickly making a video recording of a movement, or whatever. It was an induction really. Of course with the Hungary piece I kept talking with the dancers, remembering: things we saw in Budapest. Or when it was to do with the Hungarian language, and all that; of course there were a few conversations about all that. Otherwise, once I was suddenly there permanently, I had to build up experience of all these things. Piece by piece. Whichever came next. Some of them came round more often, so I certainly was assisting on pieces I hadn’t originally worked on. Pieces, in other words, which were made before my time. I remember particularly, for instance, Masurca Fogo, or The Window Washer, pieces like that. Palermo Palermo was on quite often during that time, and I soon became fairly confident with that – so I actually knew what I was talking about, and wasn’t just reading out the notes: ‘Pina says you should…’ (laughs); I actually understood a bit about what it really meant. It was very exciting. And it was very different from my previous theatre experiences. Yes, it was constantly changing. In principle I was there for the pieces, to sit next to Pina; that was clear pretty quickly. By my second season, in autumn 2000 at the latest, I was really… I sat in pretty much every rehearsal, every performance, next to Pina, took notes, the corrections. Pina was mostly there. That changed a bit over the years too. In the final years it became fairly normal that she didn’t come for the feedback. By then a certain independence had developed. Which was also a bit to do with the dancers, because at that time there were hardly any changes in the company, so although I had to talk to the dancers, they immediately knew what I meant – when I passed on comments from Pina or I’d seen something myself, or whatever. Then they always knew what the issue was. It was always pretty easy to sort out. That may be different today, now there are so many younger dancers, or when it really is a case of teaching pieces, and not just remembering something, or correcting it slightly. Yes, and then it was pretty clear. And then gradually my tasks expanded, after Matthias Schmiegeld left, to include more responsibility for touring – which didn’t mean I devised tours; Pina did that, of course, mostly together with Peter Pabst. They sat over the plans thinking about the theatres, the tours and Wuppertal, which piece would be good in which theatre. But I was the next person brought in. I went off and started trying to put it all into practice, talking the ideas through with the technical directors, the management, who were new in 2005… Going through everything, in other words, how it could all be done, same as with the rehearsal plans, once Urs Kaufmann had left. There were sometimes vacuums which I helped to fill, along with all the rehearsals and performances, which I also carried on sitting through. At some point it all changed completely, then some of it changed back. When Dirk Hesse arrived, the business of communicating with touring partners and planning had gone back a bit to how it was earlier, with Matthias Schmiegeld, with the management being more active. So it was always exciting. It was never boring. There was always something else to do, or something new or different.

Chapter 4.1

Discovering the way Pina Bausch workedRicardo Viviani:

Pina Bausch’s work has its own language, a unique onstage event unfolding. What was this discovery like for you? What new things did you gradually realise? Was there a – revelation is too strong – but were there discoveries in the language? In the theatrical language?

Robert Sturm:

Perhaps the most exciting thing for me, which I gradually realised, was this way of working, which essentially starts from the position that everything is possible. Everything I’d known till then: there was a text there, or there was a dramaturgical idea or… We’d always been looking for something, working towards something, but now the bigger picture simply wasn’t predetermined. There wasn’t really a ready-made goal as such, but – and you could really tell it – Pina did have a leitmotif, which she often didn’t explain precisely, to avoid influencing anyone. So with her questions she always provided something up front, for the purposes of investigation, obviously. But she avoided explaining too precisely what she might be looking for, or what she found interesting, so she still remained open to anything which might happen. She could change from one minute to the next, suddenly be looking for something else because a much more interesting line of enquiry had just been opened in what had just happened. I often had her next questions in my pocket, in case she came to rehearsals late, so I could tell them the next one. The dancers could start working on their responses before she arrived and present them when she got there. And I often noticed that she constantly changed this list of the next questions she wanted to ask, depending on what happened in the rehearsals. It didn’t carry on the next day as she’d thought it would the day before, with the next five questions or whatever. Suddenly there were totally different ones there because she’d seen something in the rehearsal she was excited by and preferred to go in that direction first. You weren’t allowed to evaluate either. I always had to bite my tongue. Right at the start once I said, ‘that’s beautiful, isn’t it?’ (laughs) It was funny. She didn’t want to hear that kind of thing at all. Soon it was perfectly clear why. No opinions or influences, because she was trying to decide for herself, just look at the things and then think what would fit with what, and together perhaps it would create something totally different from the things on their own. So her evaluation developed as the piece developed. It was the opposite process to what I was used to, that you started with very small things and then looked to see where it was heading till a whole was created from them.

Chapter 4.2

CollaboratingRicardo Viviani:

Wouldn’t that generate a lot of expectation or a lot of impatience?

Robert Sturm:

A lot of curiosity, I think… Curiosity… Yes. I think it takes a lot of curiosity and of course that was at the core of Pina Bausch’s personality. This is a principle which only works for me when I’ve got someone sitting there who can use their mind but also their feeling, because a lot of it was based on her feelings, and not on theories. I don’t think she was interested in theories much anyway, more that what happened was genuine, and that it moved you somehow, that it had a significance you didn’t have to explain, no message or whatever, but that it moved something in people. If it moved everyone in different ways that was good too. I think sometimes she was at her happiest when there were 800 people sitting there and each of them had seen a different piece – when you talked to them afterwards. That was completely new for me, of course, that there was a blank sheet, in every sense. Not just on paper, but mentally too, for everyone. And you only thought about the current question… And no arcs. She didn’t really want any polished… …several scenes, one after the other, or longer scenes. She preferred it as small and short as possible, with as much room for combination as possible, so she could sense where it might belong.

Chapter 4.3

Organizing materialRicardo Viviani:

And then practically: The company is not terribly big, but there are still lots of dancers, lots of ideas, lots of things which came as answers or material for these questions. How could you manage all that, organise it? What was the process?

Robert Sturm:

Pina had her established system for that. Most people would do that on a computer now, I guess. She did it on paper. She really did note down every improvisation and then she had a system with more or less crosses: what impression it made on her or how significant she found it or where it took her. And she didn’t want to see a lot of the things again at all – well she never asked again, put it that way. Because I think she… She collected everything first; she asked the questions and gathered the answers. Sometimes they were movements, of course. Sometimes she deliberately asked movement-questions, which were then recorded on video, but a lot of it wasn’t filmed in the beginning. Most of it really. In fact she told me in no uncertain terms that it shouldn’t all be filmed, because it was important to her that the dancers could reproduce the things they’d done in other ways. And she said she wanted to decide what went on video. So sometimes there were things where she thought, ‘best record that’, then we filmed it. But otherwise, when I started, in the early years, she deliberately avoided recording it all on video, because she didn’t want the dancers to just watch the video and then copy themselves from the video. There too, it was more interesting really if they did it again, without copying, using the idea they had in their heads of what they themselves had done. I found it very interesting and logical at the time. So, later that changed. Not sure if it was something to do with the dancers, but at some point – the last four years, or three or five, I can’t say exactly – everything was recorded. So the work changed and we started watching more videos: ‘how did that go, then? Let’s do that again’. But in the early stages she had a very different attitude to it, which she explained clearly to me, because I wasn’t to film.

Chapter 5.1

Job title ‘rehearsal director’Ricardo Viviani:

Then your job was given another title. You changed from ‘assistant’ to ‘rehearsal director’ for certain pieces.

Robert Sturm:

Yes, although until 2009 she was always there really. And in terms of me leading the rehearsals, I think she had a slightly different idea of what that meant. Because… I think she actually put me in charge of the other members of staff, because I was both rehearsal director and assistant. It varied. But it wasn’t just that I was sometimes rehearsal director myself, which was mostly on… …when it was to do with tours, when she wasn’t there, for instance. Then my job was to get the piece onto the stage, and there wasn’t much work to be done on the piece. That had been done already at the Lichtburg. It was more the decisions about what needed to be done because of the stage, entrances and exits, and of course more correction, even when she wasn’t there. I was rarely alone there, or if I was, I could always say, ‘Dominique’, or ‘Julie’, or…, ‘please take a look too. Something’s not right.’ As far as she was concerned, I was responsible for the whole process. She often wanted me to tell her how a rehearsal had gone which I hadn’t even led; it was someone else. I was more the link, for her, along with the rehearsal planning, but also in terms of having an overview – ‘how are things going?’ – when she wasn’t there in person, which was very unusual at the beginning, when I began, I mean. Then she was there pretty much all the time. But over the years she would sit out a particular tour more often: it was too far, or she had to be somewhere else, because of the Kyoto Prize she couldn’t be here because she was in Japan. Then she couldn’t be in Hong Kong because she was in California because of the Kyoto Prize – things like that. Then it was clear I would lead the rehearsals, but never because it was a particular piece; it was more of a general approach.

Chapter 5.2

Dance specialistsRicardo Viviani:

And for the technical side, dance, moves and all that, were particular people chosen for particular pieces? How did it work out?

Robert Sturm:

Till I arrived Marion Cito was always… Hans Pop had been there a long time. By then it was a while since he left. And when I came along it was clear that I wouldn’t… Well, that when dance had to be learned, that was outside my field. And then, when Pina wasn’t there herself, we had to decide who would take over. And so on tour, when I was looking to see how the piece worked on the stage, I ran through the rehearsal with the dancers basically, but when there was work to do on a dance, I asked someone else to take a look. And then that was established as a permanent thing. I’d been there two years or so when Pina decided she’d like to travel a bit less, so this situation, which had been the exception till then, might arise more often. It remained an exception in fact, because in reality she didn’t travel any less. But the thought was there. Then of course we talked about how this would be more complicated, because when she was almost always there, then of course I could lead one or two rehearsals on a tour and get the piece on stage properly, but if it happened regularly, the fact that dance wasn’t really my profession would be a real problem. And how were we going to guarantee the pieces if she was not going to be there on a regular basis? The result was the idea that a dancer from the company would also assist, at least on the newly created pieces. The first was Daphnis; he carried on doing most of the pieces. I was the original assistant on ten pieces, and five of them were with Daphnis. The others were divided between Helena, Barbara and Thusnelda. And on two of them there was no actual assistant present – aside from Mario Cito, was always involved in some way, but soon started doing much less assistance, really, once I was there. She was in charge of costumes, and other areas. She also wrote criticism and the like, but only occasionally. That was how the principle was arrived at, that for each new piece after Kinder there was always someone present, not just me; a dancer to assist, which then turned out to be a stroke of luck over all, when Pina was suddenly gone, because in a way we were well prepared for managing the pieces ourselves, for a while. And without losing too much of the quality. But it wasn’t planned that way. It wasn’t planned for the event that Pina was no longer with us. It was just for when she couldn’t be there sometimes, from time to time. That was the idea really.

Chapter 5.3

Job title ‘assistant to Pina Bausch’Ricardo Viviani:

We’ve discovered another title you had at one point too: ‘assistant to Pina Bausch’. Is that when this concept was introduced?

Robert Sturm:

It’s very hard to correlate the titles precisely, even for me, because often the changes to my job title were about other people. My suggestion, right at the beginning, was, ‘just call me a director’s assistant. That works because that’s what I do. Then someone else can be called choreographic assistant.’ (laughs) But she said, ‘No. We can’t do that because what I do isn’t directing.’ What Pina did, in other words. So I couldn’t be a director’s assistant. Although that would have been the most organic thing. That was my background. Now I was doing it for Pina. And it left things open for someone else to handle the dance side… But she didn’t want that. So it was ‘assistant’ like all the others. And I was assisting… Well she wanted me to help with every aspect of the job anyway. I was mostly with her in the office between rehearsals too. Rehearsal-planning work, casting work. Although otherwise there were constant changes in the line-up, I was basically required to be there permanently, to gather up all the information up continually, and later to help make decisions too. In my contract it said I was part of the artistic directorship, not just an assistant, actually a member of the directorship, because I actually helped her lead the company, and with everything involved with it – where I could help.

Chapter 6.1

Repertoire alive and freshRicardo Viviani:

Then you assisted her and you were party to the repertoire decisions, which pieces were revived, brought back in new productions to keep the whole repertoire alive. Can you say a bit about what you experienced there, the thoughts, the strategies, or how decisions were made – on gut instinct, or depending on touring requirements, or how?

Robert Sturm:

On the one hand I think the pieces always needed life – and really always had it. This is a topic which has been preoccupying me a lot in recent years: how can we teach the pieces to dancers who are not dancing their role? The life was always conveyed for me really because it was always those dancers; it was always their stuff. During the years I was involved, you could say that the pieces were by Pina but the material always came from the dancers. And because of that it was always an incredibly exciting thing to see how felt they were. They weren’t acted in the traditional sense. No matter how well an actor acts, it’s acted – normally. It’s better if it’s not so much acted, but nevertheless: it always has an artificial level. With Pina’s pieces the individual elements they are made up of, they are very personal; they are mostly filled with memories. That means of course… …on the one hand, a different kind of life on the stage, another kind of truth, if it’s those people, and a different responsibility when someone has to take over. Just copying doesn’t work with that stuff. It’s a very complex process. For someone to succeed, even if it may be different from the original, they have to convey the same thing. That’s when it gets exciting. Another thing Pina did deliberately, is that the pieces were mostly performed again after a pause, so that you got to see the pieces anew yourself, even the dancers, and Pina herself too. I always had the impression… For instance she often had a video playing along in the Lichtburg while we were rehearsing new productions. And sometimes she would say: ‘but there you’re standing there.’ That kind of physical thing. But the impression I had, and we did talk about it, was that she also used it to remind herself, the way you would use a crib sheet; she looked at it and I think it helped her remember what was going through her head at the time, what the important thing was. I don’t share the view that she was always watching the video only to reproduce everything identically. It was a memory aid for her – aside from a few spatial aspects; they were used directly. But otherwise it was a memory of particular emotions for her – remembering things again which were so pure, and undoubtedly very hard to get right again any other way, when we were working in the Lichtburg without sets. They mostly came later; you don’t get that many rehearsals in total. And so the impression from these mainly older recordings, which she used deliberately, not just so we were working from the original, but also I think so it was how it was for her, so she could just look briefly at them and then she’d recall things about what was happening in the room... It helped her a lot, even during our few rehearsals… Although the dancers recalled stuff themselves. As this was mainly their stuff it was relatively easy to remember of course. It’s not a superficial process for them, more of an inner one.

Chapter 6.2

Revisited: Two Cigarettes in the DarkRicardo Viviani:

I’m trying to see if any of the pieces which hadn’t been performed for a very long time, suddenly returned during your time. I think Two Cigarettes in the Dark? Yes.

Robert Sturm:

That brings me back to the beginning. Where I really… In that situation, when someone helped, it was always dancers who had been in the piece, who still knew the piece, after such a long time. It was the same with Keuschheitslegende (Legend of Chastity), I remember, where I still made notes though – that I remember. They still exist, somewhere. I probably passed them on, when it was last rehearsed again – at least in terms of positioning etc. I know I was there, but didn’t contribute artistically… I wasn’t part of the recollection process. And I didn’t… So my job was undoubtedly different from the others’, because I always assisted. I was generally responsible for every piece every day, and the way the pieces changed… It wasn’t the way it often is now, that we do rehearsal direction for particular pieces and they prepare intensively for that piece. For one thing Pina was mostly there with me, and later, I would know the piece because I was there during its creation myself, so then it was easy. But it was never the case that I would watch videos for weeks and do preparatory work. Instead Pina was there, and remembered it anyway, and so I helped with all the everyday work. I would still tell them the positioning from last time or note the new one – with these pieces which hadn’t been performed for ages. But artistically I was also learning those pieces for the first time. Obviously, thanks to my experience, I could still help with the processes, support Pina, but not artistically. In artistic terms I didn’t look at all, to judge the quality of the scenes and all that. Often in the initial rehearsals I couldn’t judge at all, because I had nothing to compare it to. I’d have watched the piece on video in advance, but that wasn’t enough to really get deep inside, to be able to express an opinion or know for myself what comes next. So it was always… I was very pleased when pieces came which I still remembered.

Ricardo Viviani: And a new discovery too… Yes.

Robert Sturm: The pieces themselves – and the processes too – were exciting. Because for most people it was a bit of an adventure.

Chapter 6.3

Total immersionRicardo Viviani:

Before we go any further, a few more things about this period. The logistical theatre work functions very differently with dance theatre from the way we’re used to it in other theatres, right?

Robert Sturm:

Simply the fact that the focus is 100% on each performance – or was. Essentially the way we do it is still that we work towards the performance, with rehearsals, and in that time nothing else happens. I’m talking about Pina’s time, but also the time after. On performance days, or the last days leading up to putting it on stage, we only worked on the piece currently being performed. That’s very unusual, of course, but it is also part of the unusual stage quality of the works, that we don’t just re-rehearse the piece, we re-live it – whereas in other theatres it’s perfectly possible to work on one piece in the morning and another in the afternoon. Reproduction functions on a totally different level, with a greater risk to the quality, but when it’s done well, it works. With Pina the focus was solely on the one thing. When we were rehearsing in the Lichtburg, she always tried to avoid doing another piece in between. She always tried to consolidate it. Sometimes it couldn’t be avoided, when we were rehearsing for a tour where we were performing two different pieces. Then we had to alternate between one piece at the Lichtburg and another in the theatre. But the aim was always really to keep the dancers in the one piece. There was frequent criticism, from Pina too, when we came back from a tour, or a run had just ended, and started rehearsing the next piece, that the dancers had brought rather a lot of the previous piece along. Then we had comments like: ‘This isn’t Fensterputzer (The Window Washer) any more.’ (laughs). I heard it a lot, and saw it. And it changes back again, but it does actually take time. I think thanks to this very, very… It is so total, the performing. It’s never just acted. They have to adjust themselves to it internally, not just physically, not just in a technical way.

Chapter 7.1

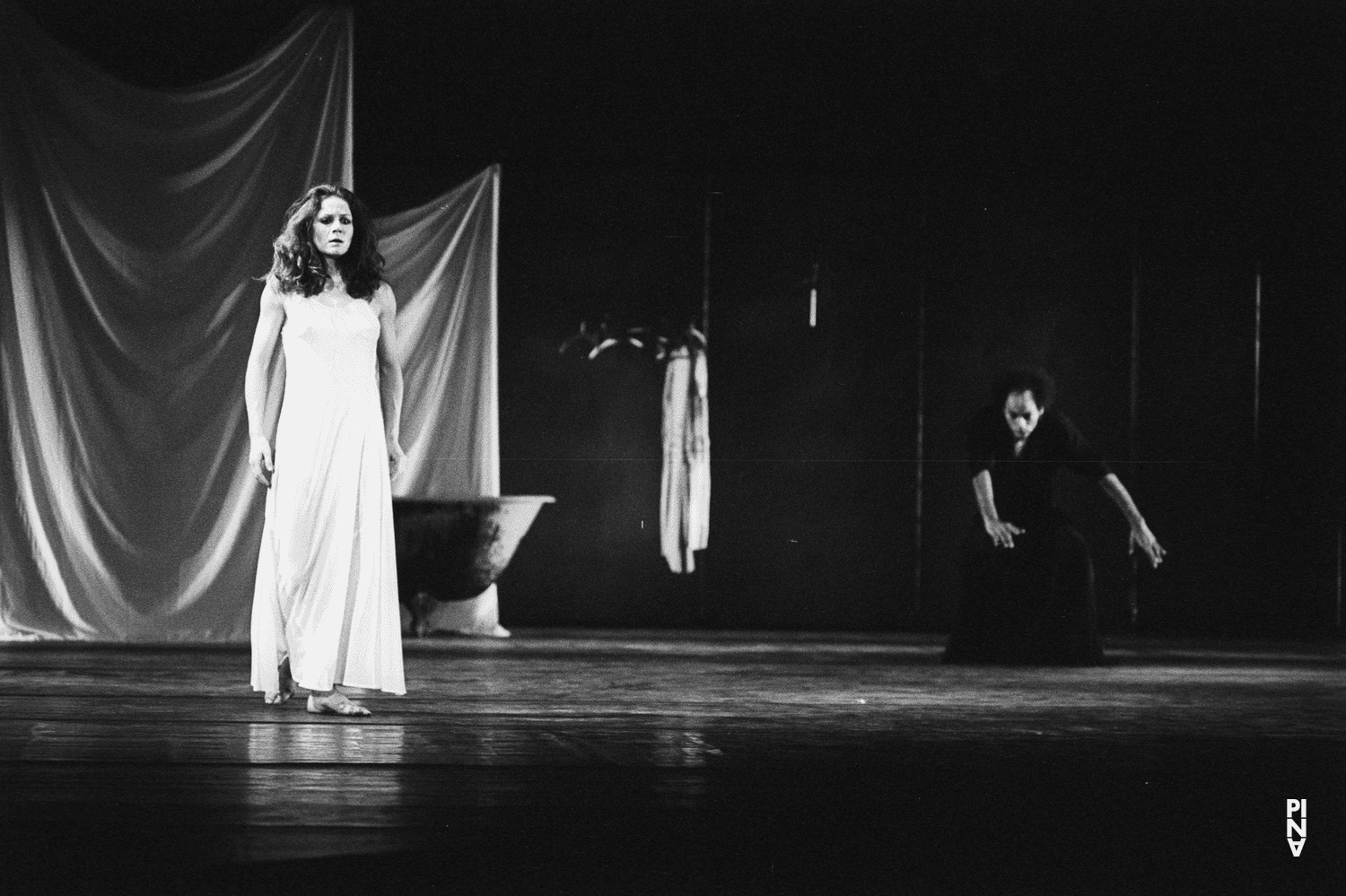

Experiences of Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

One thing is the rehearsal process for Café Müller. Did you start by… It was had already been performed a lot…

Robert Sturm:

Yes, performed a lot. I sat in the auditorium a lot. But Café Müller was a special case for me though. It didn’t work on the principle that we watched from the outside and then corrected it; Pina was on stage. I always found that fascinating. I’m sure for the first few times I just watched and checked the lighting and all that. So it never felt like correction like in the way we gave the corrections on the other pieces, where we watched and then discussed it: ‘that looked odd, that wasn’t right, that bit needs to be a bit different…’ In Café Müller there were corrections, of course, but they were always because Pina was one of the ones actually on stage; despite having her eyes closed she always had comments, but it was always a conversation between the people on stage. That only changed when the casting changed or there were double castings, when Malou was also watching or worked with individual people, then I gave comments… Otherwise it always felt to me like a tiny cosmos – which I found fascinating. I did talk to the dancers too, when I noticed something – never with Pina, about her role, because she totally had her own sense for it anyway. I sometimes said something to one of the others, but only minimally really. I just had the feeling that was the right way, that they’d sort it out amongst themselves – that was more or less my feeling – the people who’d just done it. I’m talking about the years with Pina now.

Chapter 7.2

Pina watched Café Müller after 25 yearsRobert Sturm:

There was one exception. That was in 2006 in London, when Pina got ill. She was in the clinic for a few days then she came back. Then Héléna Pikon took over the role in London at Sadler’s Wells, at short notice – she’d been studying it for a very long time. One thing I saw – just jumping back for a moment before we get to 2006 – in 1994 Nelken was in Budapest, during the period I was working there. Because of various other shows I didn’t manage to get to the performance in the evening, but via some colleagues it was arranged that I could watch a Café Müller rehearsal, very quietly, right at the back. And I sat there with my wife, as she is now, not yet then, right at the back under the circle in the gloom. Pina was rehearsing on stage and Héléna was dancing along to everything in mirror image in the auditorium. I noticed that. And as far as I know Héléna never performed it back then. Certainly not during my time, and don’t think she did a performance before that either. I think Pina told me once the only time she didn’t dance it was when she was pregnant with Salomon. And since then she’d never seen it from the outside, and then in 2006 in London Pina returned, but said, no, she didn’t want to be on stage again during this run, and suddenly there I was sitting next to her for Café Müller in the auditorium. It was really exciting, because she was seeing the piece for the first time in twenty-five years. She had a very long… I didn’t write anything down. She just watched, watched, occasionally said a few little comments, and next day she gave proper feedback on Café Müller, which went on for at least an hour or two, which I’d never experienced before, because normally they were more one-to-one talks, when it came to criticism. It was fascinating, because she said all sorts of things about the piece, which she seemed to have imagined very differently with her eyes closed on stage. For instance she changed the light almost completely. Not because it was wrong, she just said it wasn’t right any more. In other words she said, ‘sure, that may well be how it was. But looking at the piece now, it isn’t right.’ Then she made it very dark again, which it was apparently, and then lighter in places, with various moods which lasted ages, twice the time or shortened to half. With the lighting she really went back and said, ‘that’s not right, because it looks like it should maybe be one way, but it isn’t just one way; there’s various things…’ She suddenly started… We worked for ages on it in London, reworked the lighting, after she’d watched it. And since then, since 2006, Café Müller has had different lighting from ever before, because she didn’t make it identical to the way it was in the late 1970s. She redesigned it based on her current feelings in 2006 mixed with memories from ’78. After that she always performed it again, right until the end. That was a very exciting experience.

Chapter 7.3

Seeing herself danceRobert Sturm:

It was interesting in Japan too, with Café Müller/Rite of Spring at the National Theatre; Café Müller was being broadcast on TV there. And because of that they made recordings of rehearsals. And after Café Müller, Pina and I always sat and watched the recording from that evening. And she was very surprised, about herself too, and she said, ‘You know, the thing is, when I…’ It was a totally surprising thing for her, suddenly to see herself as well.

Sadly I didn’t note it all down. We should have had a little tape recorder running. That would have been interesting. Sadly I threw all my notes away, the corrections from her I wrote down too. If we’d known, it would have been good as material on the pieces. Now all we can do is remember. I think some of the others wrote more; I saw the whole thing just as day-to-day business. (laughs) Which is a pity in retrospect, because I’m sure I won’t remember everything.

Chapter 7.4

New light designRicardo Viviani:

So that means that today the lighting is the lighting from 2006.

Robert Sturm:

It would probably be interesting to talk to Matthias Burkert about that too. He was very involved with the lighting and he remembers a lot about how things different over the years because he worked on Café Müller almost from the beginning. He may have arrived one year later but he certainly did a lot of Café Müller… He can say something about the light, no doubt. What happened in 2006 really was a caesura, and afterwards I really did have discussions with former Café Müller dancers who said, ‘but that’s not right.’ And I said, ‘Yes, that’s how Pina wants it now.’ And I think we should stick with the 2006 version, because that was what she finally thought was right. The dancers who only danced it till the mid-1990s, they hadn’t seen it like that. They were always really surprised, ‘Oh, but isn’t it dark?’

Chapter 8.1

Artistic direction with Dominique MercyRicardo Viviani:

Then you became artistic director together with Dominique Mercy. How did you end up stepping in?

Robert Sturm:

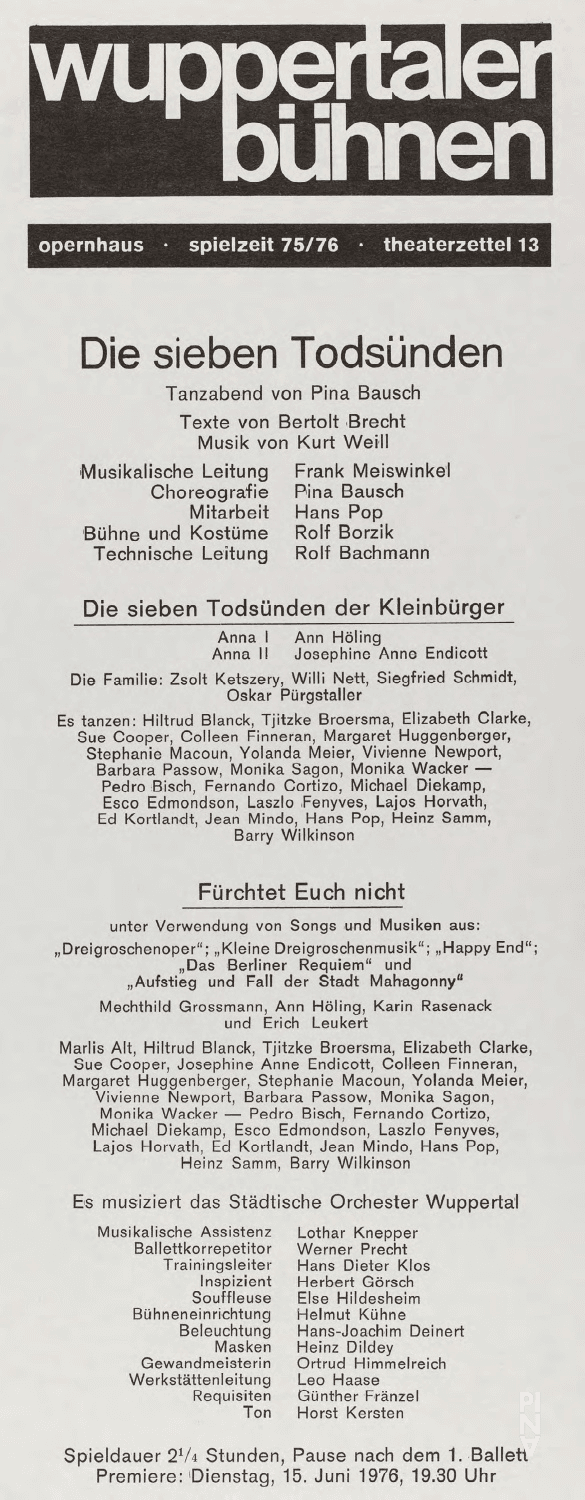

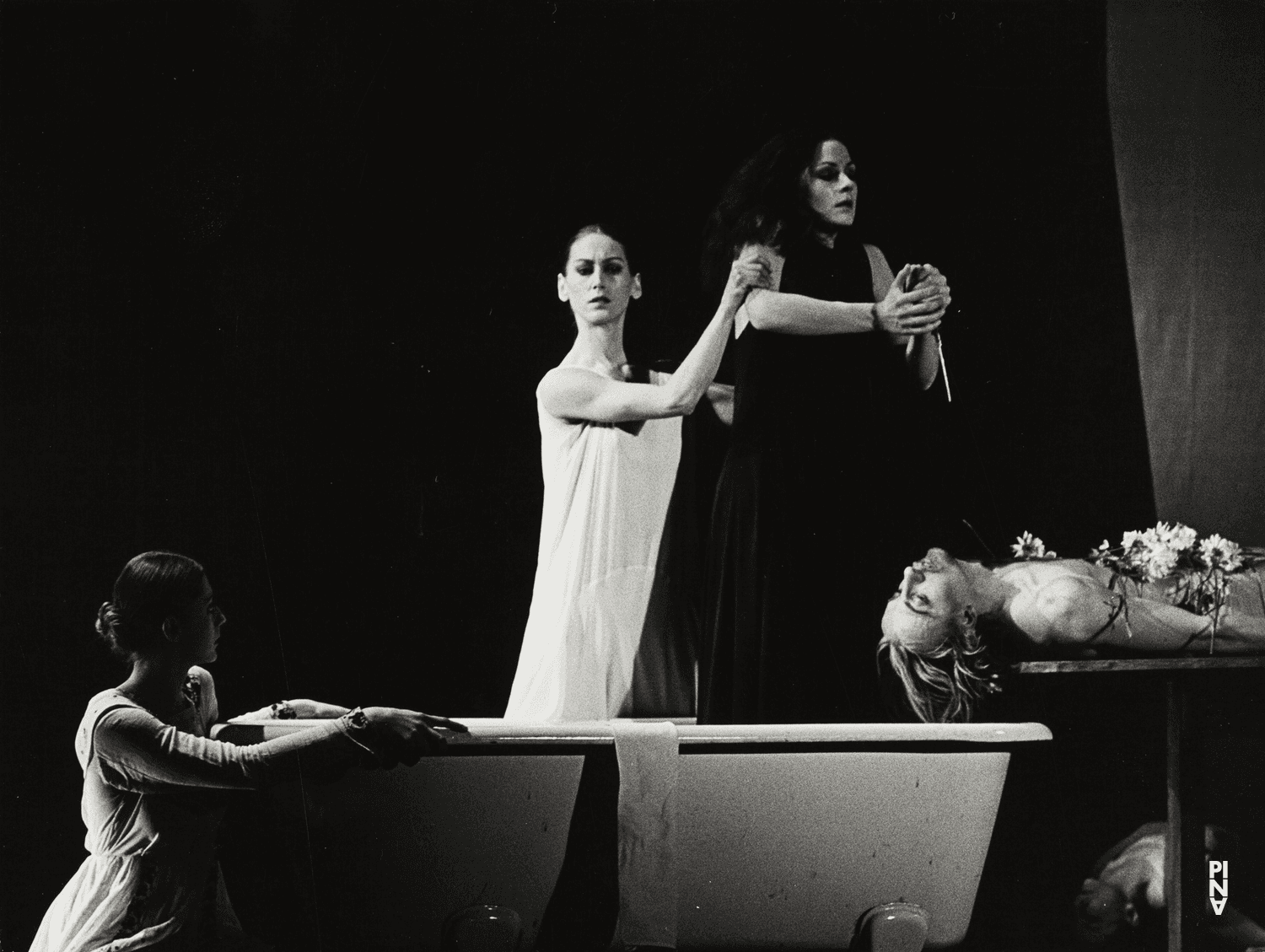

Yes, I was surprised. We could never have guessed. Pina’s death was a total surprise. Then it was quickly clear that Dominique needed to be brought in spontaneously. He wasn’t meant to have come along to Moscow for Seven Deadly Sins, but we decided he should come with us for now and we’d see how it went first. Myself, I just carried on doing what I’d been doing before. I was sitting next to Pina for ten years on lots of the things she did, while she took decisions. I did everything I could to make it all carry on running as well as possible, carried on working on the planning. But really, I think, neither of us had thought of taking over as director; the request came from the city, who had heard that we were effectively doing it already, although we didn’t see it as artistic direction, we were just doing, what we thought, what… …just to ensure continuity. They asked if we wanted to do it officially. The question surprised us both, I think, me anyway. Then we talked to the company and I’m sure we said, ‘only when no-one has anything against it, otherwise we won’t do it. If anyone says, they don’t want that…’ Because it’s always difficult to make this move from colleague to… Yes and then it was decided that we’d try it for now. It was a very difficult time, of course. No comparison with today, or six years ago, because absolutely everything was organised around Pina, and everyone had a personal relationship with her. There were a lot of questions, what the role was now, who was responsible for what. There was a great sense of responsibility, which was very good on the stage, but within the everyday work, during the process of reflection and decision-making that made it very complicated, because it created such a broad basis for discussion. Often we decided about something, but as soon as it was communicated, of course we heard ten other views. Everything was called into question, which certainly had its good side, and made sense in this company, because it is a very special company, in which, aside from Pina, responsibilities were delegated, but there weren’t clear hierarchies. And I never had the feeling myself, when we were on tour and I sometimes did the rehearsals without Pina, that it was not like it was with Pina. There wasn’t the sense that now I was the boss. These were just activities which made sense to ensure the quality or for the management. But no-one was ever deputy. At least not since Hans Pop. He was her deputy, I believe. No-one was her deputy and there was no-one who could replace Pina. Dominique was a founding member and dancer and brought a huge wealth of memory and of course a high artistic standard, but not directing experience in that sense. I was more reliable when it came to structures, as I knew how they needed to function.

Chapter 8.2

Difficulties and new waysRobert Sturm:

So we tried to bring that together. We did it with a lot of deference, and we certainly had the sense we weren’t in a classic company, where it goes (points left, right and centre): ‘So, this is what we’re doing now.’ It was also important, when Pina was suddenly gone, that everyone felt involved. It just made it incredibly complicated. And there was a lot we didn’t achieve, which we originally wanted to. I thought, for instance, that three years after Pina’s death at the latest we’d make a new piece. We even announced it. In 2012 it was announced in the press that we’d be making a new piece for 2013. But we had to cancel it again, because it was just too early. There was too much doubt. There wasn’t the receptiveness. Too many people said, which I can understand, ‘who could come after Pina?’ Big question. Did we even need another, as we had all the many pieces Pina made? So much remained unclear that at some point we said we couldn’t do it. You can’t just put someone in place who people weren’t open to, and then expect everyone to make a new piece with them. That just wouldn’t make sense. The situation was unresolved for a long, long time. There was an attempt in 2015, which was envisaged more as a work in progress, not as pieces for the repertoire. That was a preliminary step, to test out what the working processes would be like if we made new pieces, for which then ideally a new director would be sought, an artistic director.

Or maybe that was a long way from our time. In our time there was a lot of searching and some troubleshooting, because there was suddenly a lot of helplessness without Pina.

Chapter 8.3

Film from Wim WendersRicardo Viviani:

But you still managed several very important projects. For one thing the film with Wim Wenders.

Robert Sturm:

Yes, but that was planned when Pina was still around. It evolved very differently, because really it was meant to be a film made with Pina, standing behind the camera together with Wim Wenders, but also in front of the camera: about Pina’s work with the company really, on tours. That was the actual idea. Then Pina was suddenly gone, and initially it was cancelled, until we both thought, more or less at the same time, ‘A film about Pina? When if not now?’ The finance was in place, and the planning. We had the pieces in the schedule; almost all the ones which then appeared in the film had been planned and scheduled. Then came the idea to make a film for Pina, not about Pina. So it became more of a homage than a documentary in the classical sense. It was an incredibly important process. And Wim Wenders was very important for the company, because he was another figure who could generate some cohesion, via the engagement with Pina, from within everyone individually. It was improvised in the end. The filming had actually already started. We did the tests with Pina, before the summer, the first test shots. Then we said, ok, now we’ll do it. And soon after the summer came the first pieces. Pina had only been gone three or four months then. Essentially we were developing work in progress, ‘how might that turn out as a film?’ In the process Wim took up Pina’s thing in a big way, asking the dancers to say something or contribute something they would like to send Pina in farewell. That gave us various ideas which had nothing to do with the original concept any more. But the process in itself was very important. The work on the film and the work with Wim, in that season it was very important. Less so afterwards; no-one had really realised the film would go on to have a life of its own. It was just important for us, and somehow nice for Pina, that we were producing something together which was about her, which was a tribute. No-one was thinking about where the film would be shown or what prizes it might win. That was like the encore, as it were.

Chapter 8.4

Season 2012/13 in London: 10 pieces at onceRicardo Viviani:

Not just the film, then there was a season including London, with seventeen pieces – ten in London, with twenty performances – in the season. Seventeen different pieces were performed. That is a huge achievement in itself.

Robert Sturm:

There were also one or two seasons where we realised it was really too much. We pulled it off of course, (laughs) and managed all the shows to a very high standard. But not for ever. It was a side-effect in a way, because now we weren’t doing premieres any more, and because it’s better to work than not to work. And then what happened was that instead of these long phases of working on new pieces there were runs of performances. Then suddenly we were up to 110, 120 performances in a season, which we cut down again later, because it was clear we couldn’t survive that. In the long term it couldn’t be good for the quality. In that phase it still worked, because the energy… But I don’t think we should have repeated it. (laughs)

Robert Sturm:

Yes, I was co-director for that. The original idea wasn’t Pina 40, at least not in the way it turned out, it was simply the idea I had, and discussed with the North Rhine-Westphalia government, with Peter Pabst and Dominique, that we find a new director to follow Pina for the NRW international dance festival, Tanzfest NRW. Because this ‘Three weeks with Pina Bausch’ were really the NRW international dance festival. It’s just that with Pina it had been given another title, but the structure and financing were a continuation. There was the idea of choosing another director, and then at some point there was talk of perhaps having another international dance festival in autumn 2013. And then we said, ‘then remember it’s our fortieth season, perhaps we can do something special as part of the festival, either in Düsseldorf or wherever it takes place.’ Somehow the search for a new director never happened. Then came the suggestion: ‘the festival is there, the structure is there, the money is there and you’re celebrating forty years.’ And then with barely a year to go we were given the task: ‘celebrate the fortieth season, a very special one, as this festival.’ Which wasn’t originally the idea. So and then we thought about it, mainly in consultation with Peter and Dominique, and thought we’d do another three-week festival in autumn. That was the original idea. Then we had another round table on it in Düsseldorf. That included the artistic directors from Düsseldorf and Essen, and the councillors for arts for the cities. There we also talked about performing Arien again or… There were some very different ideas from what then happened, because it transpired that some things wouldn’t be possible in the time. We were just too close, because the season was planned. We had tours planned. What could we do now? Pina normally worked for two and a half years towards a festival. Now we were a year away. And then we had the idea that to celebrate the fortieth anniversary we’d orientate ourselves a bit differently and use Wuppertal as the basis – we still did a couple of days in Düsseldorf and Essen – and link it to our performance dates, which were long since planned. They were already fixed. We couldn’t alter the season, otherwise nothing would have worked. Then we took the decision to do it in four sections, because we were playing four times in Wuppertal, and to link the events to that. I think it was Marc Wagenbach who said, ‘that’s spring, summer, autumn and winter of course, just in a different order because we’re doing it in a different order. That’s a good opportunity.’ And then in the four performance runs when we’d reserved the theatre in Wuppertal, we also did other things. The Pina 40 programme is another subject altogether. You can look that up. Certainly a very big part was also… Peter also had some ideas, which he realised in part, with installations at the Sculpture Park. But really he wanted to be more in the city, wanted to have excerpts from Pina’s pieces playing in empty shops everywhere, so we had a presence. Then I had a very nice idea, because Wuppertal people know the company from the stage, and love them, sure. But we are always there. And at the same time some of the dancers came along and said, ‘we’d like to create something too, do something creative.’ And then we had the idea to go out into the city. ‘Think about what kinds of smaller things you could do, which we could show in places where there isn’t normally theatre.’ We wanted to take dance out into the city, but also invite people to conversations, where you could just listen to former dancers, or dancers who had been with us a long time. In other words, so we were more accessible, and it wasn’t just about inviting our friends to come and do shows on the stage. We invited the friends too, but more to talk about Pina and their experiences, and not to perform their shows. That would have involved more complex planning. And it turned out very nicely. It was a bit… In that particular form there was something a bit… I still hear today that it worked very well for people, because suddenly the company were really up close. And with this film series we put on, where we divided up the four festival sections into the 70s, 80s, 90s and 2000s and showed pieces from those periods in special versions or the premiere versions. It was a lot about us, and I think even for us there was a lot to discover, from the inside, without saying, ‘let’s invite this company, and this company and this company.’

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.