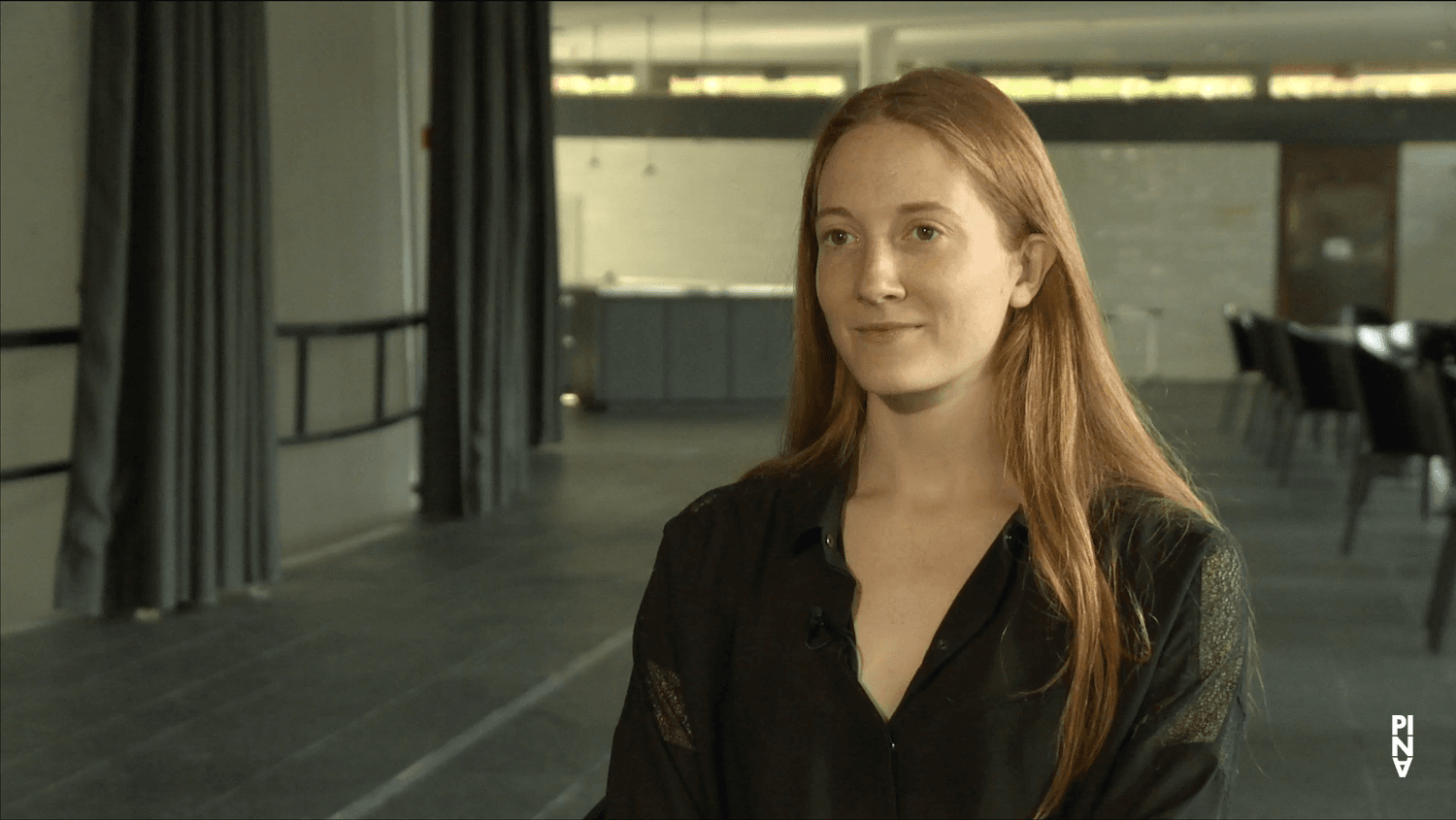

Interview with Anne Martin, 19/2/2019 (1/2)

Anne Martin joined the company in the late 1970s. In this interview, she talks about her dance education, in particular about Rosella Hightower in Cannes. Working with Gigi Caciuléanu in Nancy, she came in contact with the work of Pina Bausch during the Theater Festival. In her first season, she was an original cast member of Kontakthof, and worked with Rolf Borzik. The long tours sponsored by the Goethe-Institut in Asia and Latin America are remembered and commented. Buenos Aires provided strong impressions that led to the creation of Bandoneon. Her interview is rich in personal experience details and how these experiences influenced Anne Martin’s artistic life.

The interview was conducted in German and is available in English translation.

| Interviewee | Anne Martin |

| Interviewer | Ricardo Viviani |

| Camera operator | Sala Seddiki |

| Transcription | Ricardo Viviani |

Permalink:

https://archives.pinabausch.org/id/20190219_83_0001

Table of contents

Chapter 1.1

BackgroundRicardo Viviani:

Maybe you can share with us your artistic way into dance, your studies. We'll start with that.

Anne Martin:

The first thing I’d like to say is that it’s very emotional for me being here in the Schauspielhaus. It’s so long since I was last here, and here is still where my family is.

Anne Martin:

For as long as I can remember, I always wanted to dance. But I was born in a very small town on Lake Geneva and my parents just made music all the time; there was an awful lot of music in our family, but no dance. I had to wait till I went to the big city, to Lausanne for my Abitur, and then everything suddenly happened at once and it was like a hurricane. I saw Bejárt’s Rite of Spring. For the ten-year anniversary they did a performance with the original dancers: Germinal Casado and Tânia Bari. I saw it and was really… (gestures ‘blown away’) I don’t know how I can put it; I just thought, ‘I have to start dancing straight away. It’s live or die now.’ And then I said to my parents, to my father ‘I have to do dance now. It’s almost too late. In fact it is too late.’ And my father said, ‘If it’s too late, there’s no point starting at all.’ Of course that just made me all the more desperate to start. Gradually they accepted I wasn’t going to finish my Abitur and they arranged with my dance teachers for dance lessons every day and that I would still do a piano diploma. And then they asked my teachers if they’d be able to say after a year if I might become a dancer or not. Thinking about it today, they must all have been very brave, because you can never tell. Then I threw myself into the work: piano lessons and dancing, lessons every day. I lived like a nun.

Chapter 1.2

Rosella Hightower in CannesAnne Martin:

At some point Mudra opened, Bejárt’s school in Brussels. I did an audition. I was 19 already; he didn’t want me. Of course that made me want to give up. I should add some background: all the work going on in Germany, the Folkwang School and all that, was like an unknown planet to me. So, I wanted to give up dancing, but friend of mine said, ‘Either you stay in Switzerland and perhaps become a soloist in Geneva, or you go somewhere else and carry on studying.’ I decided to go to Rosella Hightower in Cannes. I studied three years there, really intensively. In the third year, someone came from Germany where he’d been auditioning, and said, ‘I passed through Wuppertal, and there’s a crazy choreographer there; the women dance barefoot with their hair down. It’s ghastly.’ That was all I’d heard then.

Chapter 1.3

First work as a dancerAnne Martin:

Then I got a job with Gigi Caciuleanu in Nancy. Something drove me to stick with it, but I was very unhappy. Almost every two weeks we did an operetta. Gigi was very creative and had made a lot choreographies and we were just put in stage sets where you could hardly dance at all. In one year there were only two actual dance shows, which we performed twice. We did the Jeunesse Musical (‘musical youth’) tours. I learned a lot, when I think back now: how to stay relaxed on stage etc. At the end of the first season Jack Lang, the French arts minister, organized a world theatre festival in Nancy – I’m not sure which year, 1977 or ’76, in May. There we were in Nancy Opera House when Pina’s Tanztheater Wuppertal arrived. The whole company came. We trained together. I saw Seven Deadly Sins first, and then Sacre; I was shaken up even more than the first time, (gestures) transported, however you want to put it. I was totally frantic; it was as if I’d been looking for something right from the beginning, without knowing what it was, and suddenly everything I’d been looking for was here.

Chapter 2.1

Seeing real people onstageAnne Martin:

Three things left a particular impression on me; the first thing was that I’d seen human beings on the stage, men and women; at that time in France very abstract dance was in fashion, such as Cunningham and Nikolais, and you weren’t meant to show any emotion, and here I was seeing men and women really dancing with their emotions, with these arm movements, this breath and life – I hadn’t seen this on the stage before, incredible. The other important thing was that the whole stage, everything, everything which was on the stage, was crucial to the piece. In the second half of Seven Deadly Sins there is a glass screen at the back, and sometimes someone comes and sits behind it, and just watches what’s happening. Your gaze was drawn, I remember. There were a few French people in the company. I think I didn’t sleep for a whole week; I spent the whole time with them. I watched all the rehearsals. It was incredible. But I felt far too young, far too small, to even consider I might one day be able to work with them. The next year, one of the dancers from Gigi’s group, Gary Crocker, went to join Pina and we met up occasionally.

Chapter 2.2

Choreography competition in CologneAnne Martin:

Following this experience in May, in June and July a dancer from our company in Nancy entered a choreography for the competition in Cologne; there was the dance academy there, with a choreography competition. I danced in it, and we won the first prize, and someone told us Pina hadn’t been in the jury but she was in the audience. The next day we were on the academy campus and she was sitting there with Jan Minařík. Jean Marc Forêt, who had made the choreography, said, ‘Come on, let’s go and say hello.’ I was so shy. We went over and said hello. She looked at me, like this. (demonstrates) She had tissue and threw it to me, like this. (gestures throwing) I was bowled over, enraptured for life. Then nothing really. We went back.

Chapter 2.3

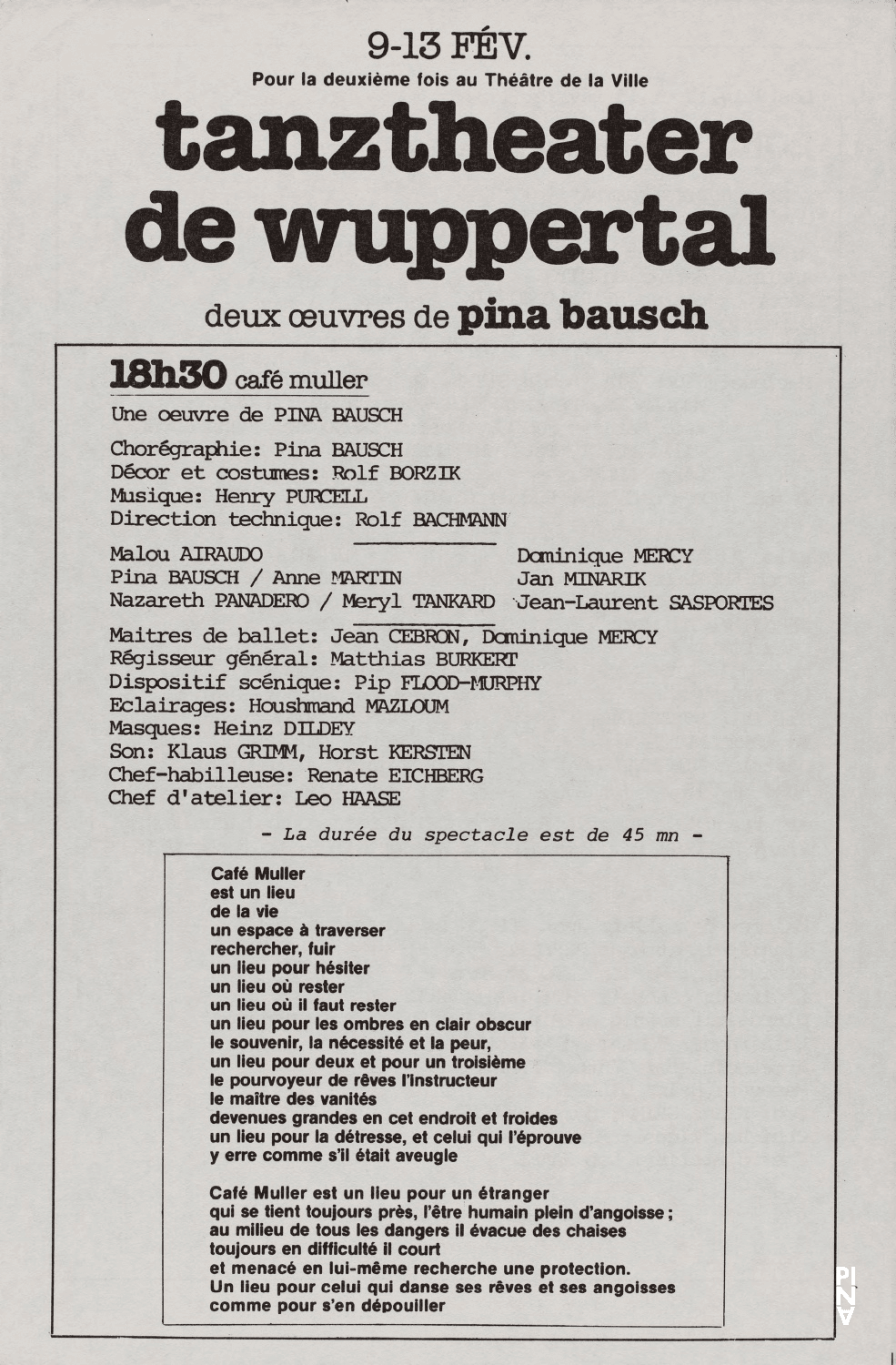

Premiere Café MüllerAnne Martin:

I saw the premiere of Café Müller, with the four different pieces. Then, at the start of the next season, Gigi Caciuleanu told us the French government wanted to set up a classical ballet company in Nancy and we would all be fired. He said, ‘If you can find another job, take it, because I can’t offer you a contract for next year.’

Chapter 3.1

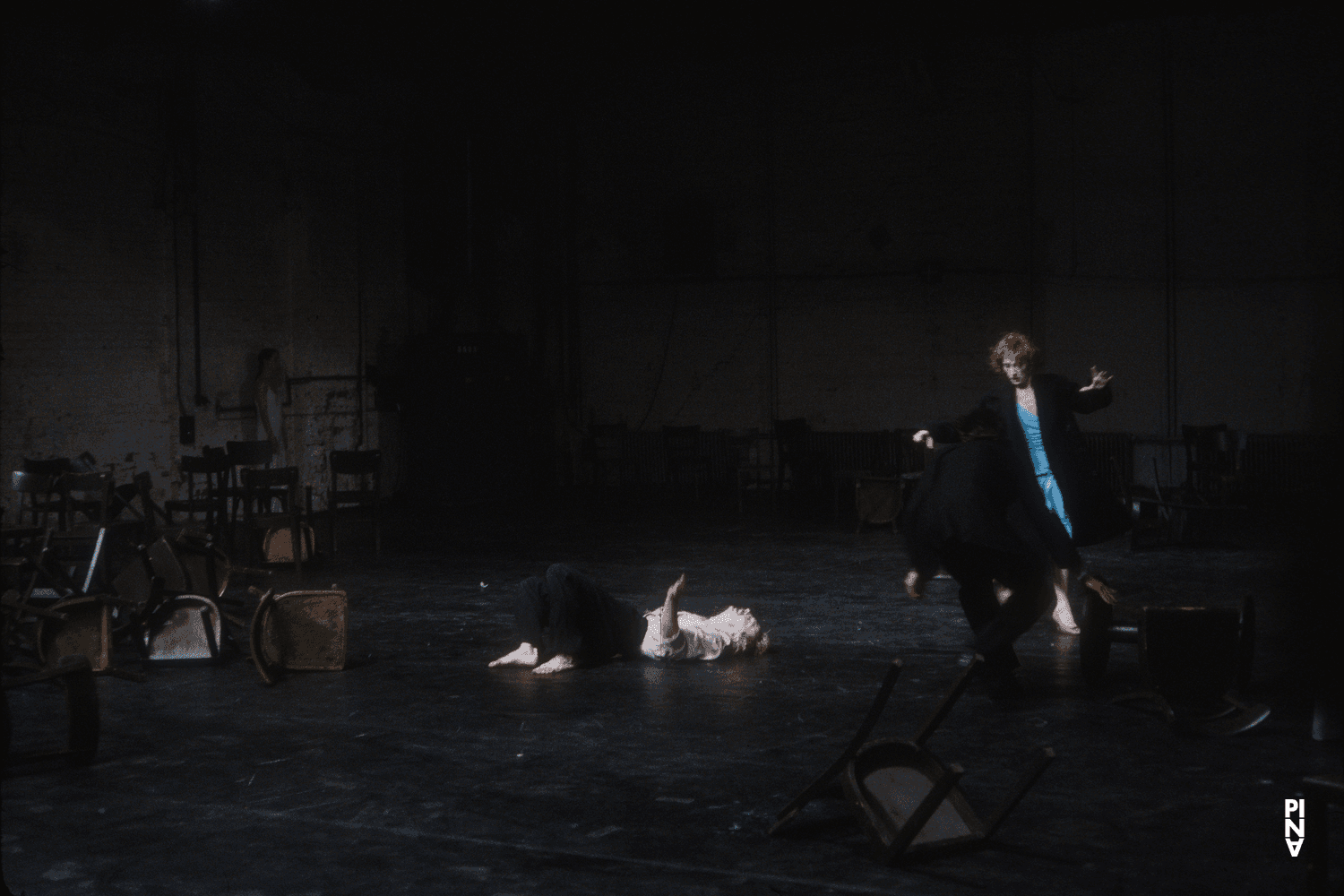

Presenting herself to Pina BauschAnne Martin:

In January 1978 I called Wuppertal. Marion Cito answered the telephone and said, ‘Ah yes, you’re the French girl with the short hair.’ By this point she’d talked to Pina. ‘Come and work with us for a few days.’ So then I went to Wuppertal. My boyfriend then was Francis Viet and he was at the Folkwang School so I stayed with him. They were rehearsing for Macbeth in Bochum at the time and I joined in for two days. It was an enormous former workshop, enormous, full of theatre chairs. On the left side were costumes, costumes, costumes, lots of pieces of furniture all around. I said, ‘May I take a dress?’ ‘Sure.’ She was asking questions, and I remember one of them was, ‘Shit, I got it wrong.’

Chapter 3.2

Experiencing the creation of MacbethAnne Martin:

At this time there were always six answers; six times ‘Shit, I got it wrong.’ That’s the only thing I can remember, but I felt so good, because suddenly I didn’t have to do anything technical, turning, leaping and all that. Because I’d started at 16/17 it was always hard for me. I didn’t have that thing you have as a child, that ‘motricité’, as it’s called in French [reflex motor skills], that just-go-and-do-it. In Cannes they used to say, ‘Hold your arms.’ But I always had these monkey arms, long arms, and I didn’t know how I was meant to hold them. I always worked with my head. And there I could just be myself and only do what I envisaged doing. Lovely.

Chapter 3.3

In the Lichtburg WuppertalAnne Martin:

On the third day we were back in Wuppertal and she said to me, ‘You can come for training in the Lichtburg and then watch the rehearsal.’ I joined them for training and Pina wasn’t there, so it was more relaxing. Then at the end of the training session I saw she’d actually been sitting up on the balcony with Rolf the whole time. I decided it was good I hadn’t seen her. At six pm there was another training session, with everyone this time, and then the rehearsal for Deadly Sins, I think. Gary Cocker, who I knew from Nancy, said to me, ‘Watch out, after the rehearsal she’ll stay here and work with you. And it’s very hard.’ I was a bit jittery. At the end of the rehearsal she came up to me and said, ‘So are you coming for some food with us?’ ‘Erm, yes, I’m coming.’ I was relieved. We were in that Greek restaurant in Elberfeld where the group always went. I’d done German for five years at school in Switzerland, but I couldn’t speak a word. I was totally silent. Everyone was drinking and talking, Mechthild, Jo; they were all there and I just sat there quietly. I didn’t understand anything they were saying. At four in the morning Pina said to me, ‘So, what shall we do? Shall we try?’ And I said, ‘Yes!’ And so that was it.

Chapter 3.4

Final season in NancyAnne Martin:

Then I finished the season with Gigi. That summer we still had work with Gigi till July. But all the new people had already joined the group in Wuppertal to work on Sacre. I arrived later, and the first thing I danced in was Sacre: the film shoots for ZDF in Hamburg at nine in the morning.

Chapter 4.1

Rosella Hightower in CannesRicardo Viviani:

Before we go into your Tanztheater Wuppertal time, I’d like to talk a bit more about Rosella Hightower in Cannes. It seems to have been an important place for various dancers. Can you describe what it was like on a daily basis there? What did you do?

Anne Martin:

The school was open to anyone; it was a private school. The first thing I did was month-long workshop in summer. I remember I worked for Kodak all of July to pay for my workshop. My parents couldn’t pay for it. The whole of August I trained. Graham technique was the only modern thing we did, otherwise classical. I could see it was a school where everything was under one roof, and – I turned 20 while I was there – I thought: this is the thing for me. Friends of mine had gone to Paris, had started working with small companies immediately, and I felt I had to work, really work a lot, lot, lot, on the things I couldn’t yet do with my body and soul. At the end of the month I said to my parents, ‘I’m staying. Give me what you can, and I’ll work to pay the rest.’ There were a few of us who were already 20, like Philippe Cohen, and in Rosella Hightower’s time we were allowed to work as ‘boursier' – ‘scholars’ perhaps? The men worked on reception; I worked in the kitchen, looked after the children, took the register. I did all kinds of things. That way I didn’t have to pay for the courses.

Chapter 4.2

Vitality, ballet and point workAnne Martin:

We had an awful lot of classical, pointe classes with Arlette Castanier. (laughs) I was the big girl and all the little ones, 15, 16, were little stars. They could do everything and I was the great big giraffe. (laughs) It was tricky but I put all my passion and energy into it. There was at least 40 of us in each class. I remember I learned how to work on my own there; when Rosella came and gave me corrections I worked on them alone for a long time. She didn’t say much, but she always noticed everyone; she had a great aura obviously, but also such vitality. She could sit on a chair and direct a whole men’s class and they all obeyed her. She didn’t demonstrate the movements with full power; she didn’t put her legs here (gestures ‘above her head’), or the feet like this (gestures ‘stretched’). But she worked very clearly with her body. Today, when I teach, I think a lot about her because she just had such vitality. That’s the first requirement for dance.

Chapter 4.3

Dance subjects in CannesAnne Martin:

During the time I was there she put on Suite en Blanc by Lifar. And there were all those young girls with such nice lines and she would dance a movement you couldn’t show in a photo, not with great lines, but she was over 50 and she simply danced it. That was dance for me. She was super.

We had jazz too – Lynn McMurray. It was… ok, jazz – modern, Graham technique, we had theatre courses too – I loved that. We had folk dance, Spanish dance of course: Sevillana with José Ferran. There were language classes too: Russian with a former dancer with black hair except for a very white bit here (points). She always spoke Russian and then she said, ‘Forget it all. Forget that.’ I learned a few words. We also had Spanish, with Jacqueline Duparc and we had music with Monsieur Pottier, a bit of anatomy, but very basic, and a bit of yoga too. I did it all, everything you could do, I did. We worked on Saturdays and Sundays too.

Chapter 4.4

Second yearAnne Martin:

And in the second year Rosella said, ‘for the exams this year we won’t do individual variations, one variation and then everyone one at a time,’ always leaving me bottom in the grades. She said, ‘Anyone who wants, can make a choreography.’ I did a choreography for three men, because I thought the women were always so mannered, lots of decorative flourishes (dances with her arms), and I thought the men were more (gestures ‘straight up’ and ‘grounded’); I could sense more of their personality. I cleaned in a hotel too, knitted leg warmers, all sorts of things. It was a very busy time.

Chapter 4.5

Gaining performance experienceRicardo Viviani:

Could you get experience of performing and being on stage there too?

Anne Martin:

Every summer we had performances in the Île de Lérins, one of the two islands outside Cannes; there was a festival every summer there. And the summer courses were great. People came from Balanchine[’s school], from Düsseldorf; Monique Janotta came regularly. Maina Gielgud came too, and Adam Lüders, [people] from Balanchine, from the Bournonville school. They were good role models for us. We were able to watch the rehearsals. One year they put on Giselle and another La Sylphide. We formed the Corps de Ballet. One year it was amazing. Maina Gielgud danced the Variations pour une porte et un soupir by Béjart, with music by Boulez [sic. – by Pierre Henry] on the island. There was a lot of wind. There were trees in pots and in the strong winds they fell over, but she stood on one leg en pointe for an incredibly long time, no problem. Other times we were the Corps de Ballet, outside, next to the lamps. Then the mosquitos came. You’d be standing there and then it was iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii (sound of mosquitos) (laughs) and you couldn’t move. Those were great experiences for us of course. Giselle with Maina Gielgud: she knew Gigi Caciuleanu very well; she organised to perform in Nancy too, where Gigi already was, and she needed a few more Corps de Ballet, so a few of us from Cannes went to Nancy. I was part of it. I watched the women in the company, and during the rehearsals they sat at the side knitting. They would get married to the director’s son, and I thought, ‘My God, I really don’t want a utilitarian life as a municipal employee.’ It wasn’t my idea of dance at all. It was an experience.

Chapter 5.1

Gigi Caciuléanu and FolkwangRicardo Viviani:

Gigi and Pina Bausch had already met in Nancy.

Anne Martin:

That was in ’77, and in ’78 Café Müller came and we knew that was down to Gigi. Jean Marc Forêt, who did that choreography – also knew Guy Detot, a French man who was in the group. There were already some connections. Once in the abbey in Pont-à-Mousson [Abbaye des Prémontrés], near Nancy, there was a showcase including Susanne Linke. She did Death and the Maiden by Schubert with a woman from the Folkwang School [Vivienne Newport]. That was really beautiful. And Malou and Dominique danced that night too, but I don’t know what any more. It was the first time I saw Malou. (gestures powerful dancing) I was very impressed. Who else…? Yes, a piece by Gigi, and when I first saw it, I didn’t really like it. I found his dance too hectic. I have to say that Gigi was very nice as a person, and a creative person, very generous, and he could create thousands of movements in minutes, just a few too many perhaps.

Chapter 5.2

Working in NancyAnne Martin:

At the start of the second season he had the opportunity just to make new pieces with a part of the group, and the other half did the operettas. Luckily I was in the good half, and for me and Yveline Lesueur he made the Pavane pour une infante défunte by Ravel and we really worked in collaboration with him. That was wonderful. I have to say, that at the time I still wasn’t sure I could do that. I loved it and I did it, but I always had the feeling I was a bit behind. We danced the Pavane pour une infante défunte in Saarbrücken. After the performance a young woman came up to me and said, ‘You moved me to tears.’ Then I thought, ‘Ok I’m on the right track.’ Only one person said that to me, but I thought, ‘then it’s right.’

Chapter 5.3

Gigi and Pina – being truthful to oneselfRicardo Viviani:

Gigi won the competition in Cologne two years running and Pina invited him to the Folkwang School to choreograph. He made several pieces there. You worked with both of them. Can you say, from your experience, what brought these two artists together?

Anne Martin:

Strange, I never thought about it. Really I came to Gigi from a totally different place. That was through Rosella. She knew Gigi and had supported him a lot in France. I never thought about it. For me it was just a journey I was trekking along. I think it was more Gigi the person – he was very authentic as a person, and perhaps it’s that which drew him to Pina. Although in the piece he made with Pina, his Café Müller piece, there were personages, the General, the Countess, the child, theatrical protagonists like in classical dance, which is where he came from anyway, but he was always authentic on the inside and I think that’s what connected him with Pina most strongly.

She knew that on that bill [Café Müller], Hans Pop, for instance was from the same family as her, as it were, and Gerhard Bohner wasn’t, but he had something a bit heavy about him. Maybe she knew Gigi had a different vitality and buoyancy. Maybe, I don’t know. It’s just a thought. His piece was amusing, as far as I can remember.

Chapter 5.4

The first work with TanztheaterRicardo Viviani:

Let’s return to the early years of the Tanztheater Wuppertal. Your first piece was Sacre; how was that?

Anne Martin:

As I said, I came later, in August, and I learned it all with Yolanda Meier, very quickly, and joined straight in. They had a performance in Edinburgh first, at the festival. There was no room for me in the plane and Rolf had the wonderful idea (gestures a kiss) that I travel in the truck with the sets, with the two men and me in the back – in this huge truck to northern France and then on the ferry and up to Edinburgh: it was super – and back of course. I wasn’t dancing; I just watched. I was there. The first time I actually danced was at the TV studio in Hamburg. You have no time to think in Sacre anyway. (laughs). But when I think about it today…

I hadn’t had the whole preparation which Beatrice, Lutz and the people from the Folkwang School had. They had worked a lot with Jean Cébron, and they had this whole quality to their movements (gestures), which I didn’t. Even with Gigi – I was sorting out papers recently and I found a photo where there were three of us in a piece by Gigi in a forwards movement (gestures) and all the arms are different. I’m like this, the other one like this, the other one… I know that with Pina everything was important. The hand must be like this (gestures) and not like this. All the details were important, and with this incredible power in the movements too. It was very precise. I really tried to get the movements right. Then you just had to dive in and you had no time to think till the end.

Chapter 5.5

The Stravinsky programAnne Martin:

At the start Barbara Passow was still there for the film; I danced at the back. After that I took over Barbara’s role, lying on the red cloth at the start of the piece. The Stravinsky show was a whole evening of dance. I learned Cantata too. In our repertoire we had: Deadly Sins, Come dance with me and the Sacre triple bill, including Cantata, a very nice piece to dance, and Second Spring; I had the role of the bride – the woman in the bride’s dress who drifts around. That was wonderful. I liked the show a lot when we did our Asian tour that first year. Dancing the three pieces one after the other was wonderful. Cantata was a phenomenon, Second Spring was very different, and then Sacre.

Chapter 6.1

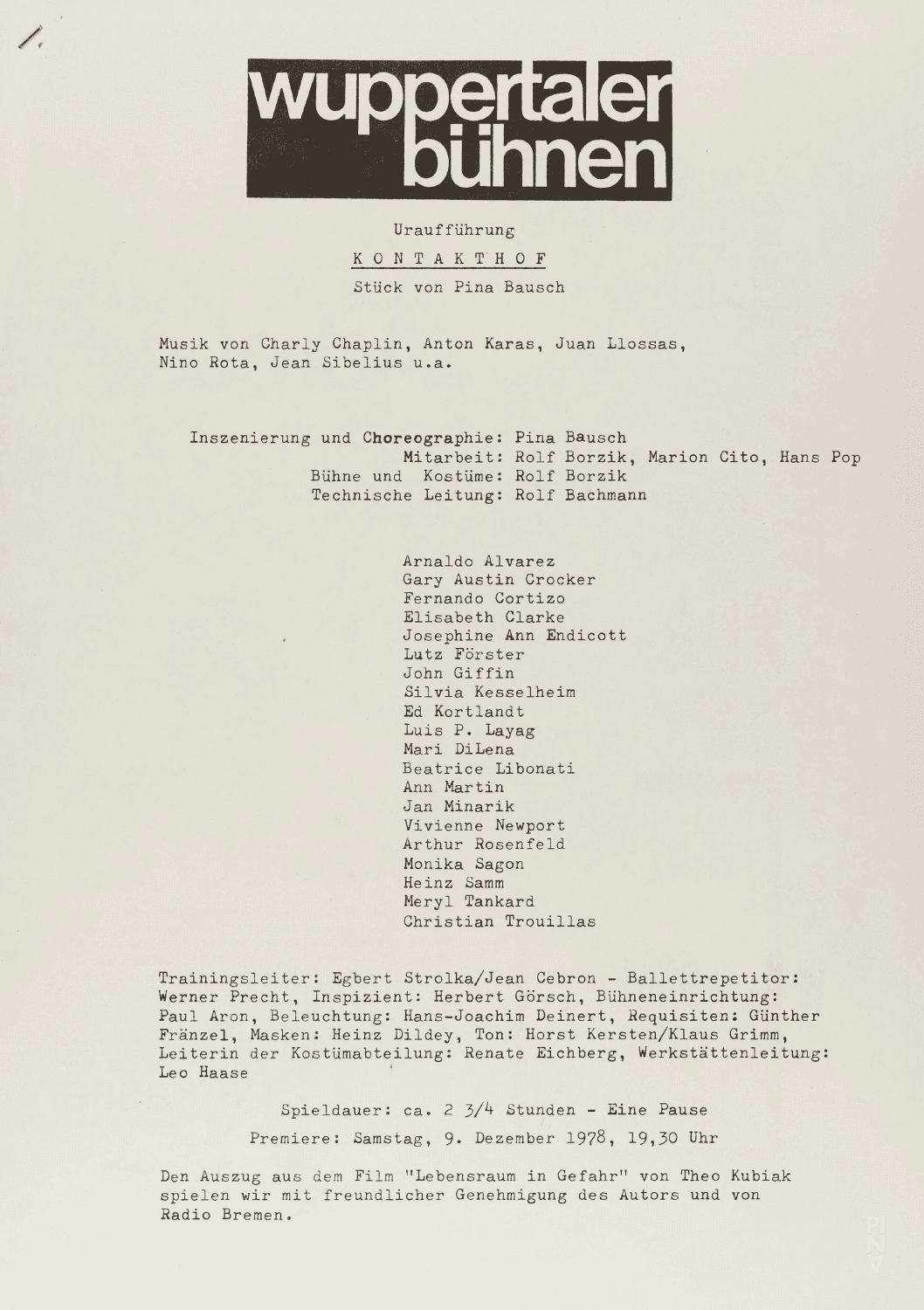

New members from the companyRicardo Viviani:

That was a season when lots of people left and lots of new people came.

Anne Martin:

Yes, there were seven of us new people. There was Meryl Tankard, Christian Trouillas, Arthur Rosenfeld, Beatrice Libonati, Lutz Förster, Silvia Kesselheim and me.

Anne Martin:

Yes, Kontakthof…

She asked questions, a lot about affection, little gestures of affection you make towards someone else. I was quite astonished that she had retained my movement (gestures arm raised) for everyone to do. It was really incredible for me. I think I, and all of us, we all totally trusted and admired her. I didn’t question it; I just did it. And I had no sense of how I came over. That’s very important in this work. For instance, some time a long time afterwards she said how important she found it that I’d done it that way. It was in the doorframe. At a moment when not much was happening I went over there and just positioned myself like this (stretches arms over her head), with my monkey arms – four movements like that. I had no idea, but it was crucial that I had no idea, because you had to stay humble, and not think you were personally important.

Chapter 6.3

ImprovisationRicardo Viviani:

Responding to the questions – some describe it as improvisation – it wasn’t tricky for you?

Anne Martin:

It wasn’t improvisation. No, it was wonderful. I really loved doing all that. We worked the whole time on that piece with the Juan Llossas songs. We did something and she put a bit of the music on. Gradually we ended up with just a few songs, but at the start we were working with the whole record. I really enjoyed it and I didn’t have any doubts about it at all.

Chapter 6.4

Seen from insideAnne Martin:

And I have to say (laughs), that it’s so funny. At the premiere I thought, perhaps it’s… When I’d seen Pina’s pieces before I was so impressed: Come dance with me, that opening… (gestures) It was all so strong and really left an impression in my heart and in my soul. Now I was on the stage and thought, ‘Perhaps it’s not as good a piece as the others. Because it’s easy for me. I don’t have to think: I have to do three turns here or something tricky.’ I just had to be myself. I thought, ‘Perhaps that isn’t such a great piece.’ When I think about it now, it’s one of her finest pieces.

Chapter 6.5

A piece of the wholeAnne Martin:

What I really loved was, we could all be totally ourselves, but within a larger framework: not just myself, but also myself in connection with something else, with this and this. That’s the most important thing in theatre, in dance. I can’t imagine dance performances any different – the way things are arranged on stage. There’s a very fine text "Notes on the melody of things" by… I forget… where he talks about just this. He talks about a couple sitting at a table and talking. But this conversation means nothing if you can’t hear the thunder in the background from the storm approaching. All of Pina’s pieces are constructed like that. And there’s a composer, Heiner Goebbels, who also made things like that. The barking dog and the lights from the car and the poem and the person singing – they are all part of his music. With Pina it was just the same, in her pieces: everything that was here, and here (gestures). It’s wonderful, because it’s all together there.

Rilke! (laughs)

Chapter 6.6

Getting used to WuppertalRicardo Viviani:

So lots of new people arrived and a new piece was created. Did you feel at home in Wuppertal?

Anne Martin:

It was all new to us. Being in Germany, oh my God, not really understanding the language. But there were a few of us French people. Malou and Dominique weren’t there any more, but they came by every so often. Christian Trouillas… Ed Kortlandt spoke French too. There were older members like Monika Sagon, Monika Wacker with her husband – who left later. They were very nice to us. There were no problems with them. I have to say the work was so intensive and everyone was so busy with their own things that we didn’t spend that much time together outside. One time I went to Ed Kortlandt’s place and it was funny to see how a person lived outside of work, to see his flat. We were working at least ten hours a day after all.

Chapter 7.1

Arien: Impossibility of coming togetherRicardo Viviani:

And then the rehearsals were always in the Lichtburg. Arien: were you part of the creation process?

Anne Martin:

I was part of it, yes. When was that? After Kontakthof? [1979] At that time we created two new pieces each year. Crazy. Yes I was part of Arien… I can’t remember so much about it. But it was really great. We knew there would be water, but we didn’t have any water till right at the end. I enjoyed every bit of it, loved it all. It was hard for me because my private life was difficult. I had heartache, but I was able to put it all into the dancing. That piece is also about the impossibility of coming together; it’s a lot about that, but also about death somehow. There was one part when we were all in black. It’s like a burial, but with the urge to live, to stay above water and to love. It was so relevant to me I threw myself totally into it.

Anne Martin:

I loved him a lot and he also made a great impression on me. I didn’t know him that long: one year, on tour a bit too, but on the first tour I wasn’t with them the whole time. They had a smaller group of people and I was with the newer people. It wasn’t as intimate. But I also loved him because he had such a sharp eye. You couldn’t kid him. You might play around but he had laser eyes and would say something. Pina had laser eyes too, but she just looked. I liked that, that you couldn’t cheat. You could play, but you couldn’t cheat, and I loved this. I really loved it. I know one time I arrived with a red ribbon in my hair – no idea what I’d been doing – or perhaps plaits, and Pina looked at me and said, ‘Well it looks a bit like a Christmas tree, but on you it’s ok.’ (laughs) Rolf always kept an eye out. I loved his eye for detail, his whole attention to detail on stage.

Chapter 7.3

Detail in BluebeardAnne Martin:

In Bluebeard, among the leaves there was a dead bird, a stuffed bird lying around. No-one in the audience noticed it but it was important.

Chapter 7.4

The right worn-lookAnne Martin:

In Kontakthof he didn’t want the wardrobe women to iron the costumes. We did iron them later, but he hadn’t wanted that. He wanted this satin to look a bit lived in, not ironed. Afterwards that wasn’t what they did, and they got very clean again, but he liked that not-quite-clean look, wanting to be clean but not quite being clean. I loved that about him.

Chapter 7.5

A genius with materialsAnne Martin:

Once making the costumes for Keuschheitslegende [Legend of Chastity] he was trying out things for the costume and there was a piece of velvet. I was standing there and he said, ‘Wait a minute.’ And he wrapped it around me, tied a golden bow here, and it was a dress. Then they sewed it together. He was a genius, that man, really.

Chapter 7.6

Legend of Chastity – creative disputesRicardo Viviani:

Legend of Chastity was his last piece with the company. How was the communication with him?

Anne Martin:

After rehearsals we always went to Mostar, a restaurant behind the Lichtburg. No idea if it still exists. It was a Yugoslavian restaurant; at that time you called it Yugoslavian. He liked the cherry pancakes, Rolf, and we would stay there. I liked these moments a lot, because once Pina had had a bit to drink she would say, ‘We can really talk freely.’ But sometimes they really argued, the two of them. And sometimes he slammed the door and left. It was really… well, very creative.

Ricardo Viviani:

So you discussed artistic issues?

Chapter 7.7

Borzik’s passingAnne Martin:

Yes, and other things too. I can’t remember what any more. They didn’t always agree about things. I think we had just got Keuschheitslegende finished and had a couple of weeks free. He was involved the whole time, right till the end. I wasn’t so close to Pina at this time and I remember I needed to get away for a few days all on my own. I travelled to Venice on the train. I stayed three days there and just walked through the streets. One day I was on a bridge and I saw there were bas-relief carvings on it, with a lion’s head, and I swear it was Rolf’s face. It felt like a knife in my heart. I called and he had just died. It was so powerful. After I got back I went to see Pina a lot. I spent whole evenings with her, just being there. After that I was very close to Pina.

It’s funny. The memories come back when you ask the questions.

Chapter 8.1

Goethe Institut toursRicardo Viviani:

We’ve reached the end of 1979, start of 1980. Rolf died at the end of January 1980. Were the big tours just before that?

Anne Martin:

The first tour was '79 in February. I know the date precisely because the first city we were supposed to fly to was Teheran, in Iran, and the revolution was just happening. We had to cancel. The funny thing is that I lived with an Iranian man for 15 years. He wasn’t in Iran at that time, but it was very strange the whole story.

Chapter 8.2

With someone – not under someoneAnne Martin:

We set off, I think at the start of February. It was crazy. At that time everything was new to me. We travelled through the whole world. In six weeks we were in India, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Bangkok, Seoul, Hong Kong, then back in India. It was just crazy. At the start we did Seven Deadly Sins and the Sacre triple bill. After that Deadly Sins was cut. Then we just performed the Sacre show. We used every second, loved everything. I remember in India after one of the performances the stage hands were lovely, but very slow. So we – Yolanda and I – rolled up all the carpets, and they said, ‘No, no. We do this. We do this.’ But they were so slow we all helped. We were together a lot, not with Pina so much in my case – more in the second tour.

It was the first big tour for Pina too. When she came to Nancy that was her first time in France. Everything was the first time. I’m so grateful I could be part of this time, with someone and not under someone.

Chapter 8.3

Small and large stagesRicardo Viviani:

As you say, it was the first tour. How was it with the varying dimensions of the stages?

Anne Martin:

That’s a good question. The whole Stravinsky evening… Cantata, with its curtains, was like three chambers. But somehow in Bangkok the normal stages had steps, totally open. You couldn’t use the curtains there. The best time was in Seoul. That was a huge theatre with 4000 seats and when they hung the curtains it looked like washing on a line. Then they said, ‘That makes no sense. We don’t want to make the stage smaller.’ After that we just danced Sacre, didn’t we? Or did we do all three for the whole tour? I’m not sure any more. It’s a long time ago.

Chapter 8.4

Time for adjustmentsRicardo Viviani:

Always with enough time to fit everything, the appearance ways and everything?

Anne Martin:

Yes, but not much time. We set off from here in the middle of winter and arrived in India where it was 30 degrees Celsius and very humid. Lutz, Hans Pop and Monika Sagon, the actual Germans in the group… (laughs) Lutz was incredibly ill because he couldn’t handle the heat. I love heat; for me it was no problem, but for a few people it was really difficult. Then in Seoul it was minus ten; in South Korea it was midwinter too. It was really… (gestures ‘see-saw’). You learned how to wake up in the middle of the night and dance Sacre. It was pretty amazing. I never found it too hard to take. There was so much to discover, all of it wonderful. I just got a bit of stomach upset, which is normal. At one point in Kolkata it was tricky. There was a political conflict. We were in the middle of dancing Sacre when suddenly some people started shouting and came up on stage. We drew the curtains and stopped the performance. We thought it was against us, but it wasn’t at all. It was between two political parties. In the hotel where we were staying there were posters from the unions demanding just a bit more than 3 Marks – 1.50 Euro today – a month. Of course you could buy more with that there, but still. So it was a bit eventful in Kolkata. It was a crazy city altogether. But we just arrived there and danced, did what we had to do as well as we could. Then we explored the surroundings. I think I remember more about the experiences out and about than in the theatre – except for these theatres in Kolkata and Seoul, and Bangkok.

Chapter 8.5

Exploring places and the later workRicardo Viviani:

That’s interesting, because suddenly you’re saying.... or I’m wondering: Was there already a bit of curiosity there for what came later, the coproductions with other cities, engaging with locations, taking something from them and making an artistic product.

Anne Martin:

Yes, yes, but I have to say, from the point of view of what impression Pina’s work made, we did these two tours because at the time the Goethe-Institut was supporting us a lot. We met people from the Goethe wherever we went. They organised so-called parties for us – they gave us receptions. But in terms of the audience it wasn’t always easy to see that. Even in Paris, at that Deadly Sins/Bluebeard show we did in the first year – we danced Bluebeard and Deadly Sins after the 1979 Asia tour in the Theatre de la Ville – people were shocked. The reviews were really very bad. The audience were very divided, but the reviews were just bad. They really didn’t like it at all. During Bandoneon, one year later, people walked out, slammed the doors, threw tomatoes onto the stage at the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris.

Anne Martin:

[Tomatoes?] I think so. They threw something onstage.

I can’t remember any more, but they threw something at the stage. It was pretty extreme, oh yes.

Chapter 9.1

Swift processRicardo Viviani:

1980, after Rolf’s death. It was a swift process, right?

Anne Martin:

I can say a bit more about that, because I was pretty close to Pina. She as wondering, ‘What kind of piece should I make?’ She had to do a second piece that season and it was the first time we were to make a piece here, in the Schauspielhaus. Till then both pieces were always in the Opera House. She was wondering, ‘Should I make a really crazy piece or a really sad one?’ And she couldn’t decide, and dragged it out right up till we started. Then we made a piece in six weeks and she never revised it; it stayed as it was. Some pieces, like Nelken for instance, she carried on revising years afterwards. That was insane. We were all together in the moment. The piece has all sorts of levels. There’s affection, memories, sadness, grief, joy; there are really so many levels in that piece.

Chapter 9.2

Sprinkler danceRicardo Viviani:

Let’s talk a bit about your solo with the sprinkler. What was the creation, the genesis of it like? Did the movements come from Pina, or from you?

Anne Martin:

Yes, it was the first time in my life I did something without questioning it, I just…

At that time she was asking questions and we responded. It didn’t necessarily involve the six phases any more. For instance, there was the tea time scene with Vivienne Newport, who was English, playing the queen with the tea. She wanted ceremonious formations. We did various things all together, and between the questions she… One day we arrived and she showed us a movement. We all learned it. I think I retained it, because I found it so beautiful. At some point that day, that I do remember, I was facing backwards in this formation. She was sitting there at the front and at one point she said, ‘Someone go and dance.’ Everyone waited, and I just went up, without stopping to question it. Till that point something had always held me back, telling me, ‘No, you can’t do it. It’s not for you,’ not telling me intellectually, but emotionally. And then for the first time I just went up. And I didn’t do very much, but afterwards she asked me to come one Sunday, and we worked on longer movements, and she said to me, ‘Yes, you should end that big movement with this skipping.’ And so we created a long phrase. And she said, ‘You can create another phrase from the smaller movements.’ So we just made that passage together. But they were her movements. I just put them together, and one of the movements she said, ‘Yes, you can do that very tiny.’ We did that together.

Otherwise, there was the matchstick figure thing. She just said, ‘Matchstick men,’ and I did it. And it stayed that way. But even then I needed a long time to feel really, really good about it. At first it was tricky. The pieces of turf weren’t any bigger than that, (gestures small size) so you did a turn and the grass all came with you. But with time I got the hang of it.

Chapter 9.3

SerendipityAnne Martin:

In my first years she saw something in me that I didn’t see at all, and I trusted that – I can say that now. At the time I was trying, but something always held me back. Once I had to stand in for Jo in Arien and as I came on stage my feet started trembling. It was terrible. It took time till I gradually got over it and could just dance. Later it worked. And I think the thing with the garden sprinkler was one of those things I loved about Pina. It’s something she hadn’t necessarily prepared in advance. She never thought, ‘We’ll get a sprinkler and she can dance under it.’ But at some point the stage hands were watering the grass and then she said, ‘Go on, try dancing under it – and you have to stay under it the whole time.’ That meant the movements were always cut off, but that was very beautiful. In lots of the pieces she found things like that.

Chapter 9.4

Personal growth as an artistRicardo Viviani:

You said in this period you got closer to Pina. Did she help you find aspects of yourself as an artist, as a dancer?

Anne Martin:

I was in Nancy with Francis then – he came from Nancy – and then we saw the performance with Pina. After that we went to a café, that big one on the Place Stanislas, Café du Commerce or some such. We were sitting there at a table and she said to me, ‘Ok, I’d like you to learn Café Müller.’ (gestures ‘bowled over’) Immediately, for the first time ever, something in me said, ‘Shut up! If Pina thinks you can do it, you can do it. Stop prevaricating and being afraid and all that. Just do what she says.’ (laughs)

Chapter 9.5

Restaging Café MüllerRicardo Viviani:

Dominique and Malou weren’t in the company any more at this stage.

Anne Martin:

No, but they came back. They knew they’d be back. They danced in Nancy and they came with us to South America on tour.

Chapter 9.6

Ancién Garage in NancyRicardo Viviani:

We have photos in the exhibition from Nancy which Jan took of the performance venues. It was a car showroom – do you remember?

Anne Martin:

I remember that it was all through a plate glass window, but more than that I don’t recall. It was really amazing. It was a place for displaying cars, a showroom, with all the walls made of glass and the cars inside. They put the sets inside and it was amazing. There was tiered seating outside and you saw it all through those windows. It was very, very beautiful.

Chapter 9.7

Festival in NancyRicardo Viviani:

What was it like in Nancy? The Nancy theatre festival is at various locations. Was it a normal auditorium, because in the photos it looks somewhat improvised.

Anne Martin:

No, no, that’s the way it was. I remember the first big theatre festival better, because everyone in the world making theatre at the time was there. Tadeusz Kantor, STU Theater from [Krakow] Poland, who were under a tent, La Mama Theater, who did something in a flat – no, that was in Cologne with La Mama Theater; at the start the audience looked through the windows and then walked through the flat. That was very avant-garde theatre. In Germany they had that a long time before France, by the way. That was something very new for France. Kazuo Ohno was there for the first time. There were performances throughout the city. Someone did performances with rubber gloves all around a fountain. There were things all over the city, and I can imagine that Jan and Pina and their people chose that location and preferred it to a normal theatre. No, it certainly wasn’t improvised.

Chapter 10.1

Casting issuesRicardo Viviani:

We’ve got to the South America tour now. A lot happened there. In the programme Café Müller has lots of different casts, which wasn’t the case later. Was the company involved in the overall theatre work at that time?

Anne Martin:

One big thing was that Jo left. When was that? She was still there for Keuschheitslegende. For 1980 she was still there. But she didn’t come for the South America tour. We did Kontakthof and the Sacre show with Café Müller combined with Sacre for the first time. Jo’s role in Kontakthof was divided; I played the blonde Claire. It was great doing that in South America. I loved it. I remember that ‘wah, wah, wah’ (demonstrates dance with sound) (laughs) We did Zweiter Frühling (Second Spring) I think, because I played the bride. I can’t remember. I have holes in my head. Maybe not.

Chapter 10.2

No climate shockAnne Martin:

We did Café Müller – of course I wasn’t doing Café Müller for Pina yet; Pina danced it – and Sacre. And it was very different from the Asia tour. On the Asia tour we were in each place for four or five days and kept moving. This time we were longer at each location, a whole week in each town. When we flew out, on 5 July I think, early July, it was around 11, 12 degrees, typical weather for here, raining, and we arrived in Curitiba, southern Brazil, and it was raining there, same weather and we thought, ‘Oh no, we wanted to go to Brazil.’ The people from the Goethe-Institut wanted to give us a treat and they took us to a restaurant called Schwarze Katze where we got [German style] potato salad. We were bitterly disappointed. Brazil. Then we went to Argentina.

Chapter 10.3

Organization: Sets and propsRicardo Viviani:

Excuse me – did the walls for Café Müller and Kontakthof come with you?

Anne Martin:

I think so, because the sets had to come by boat. We had everything with us that time. Yes, we had the walls.

Chapter 10.4

Turning point in ArgentinaAnne Martin:

In Argentina our world was turned upside-down. We were in this tango city. We went to massive venues, where people dance, where couples go and dance. It was suddenly like in the 1940s; they were older couples, the men in suits, green plants everywhere, and they danced so beautifully. Dancing in pairs. It was wonderful. As I was with Pina a lot, I was always involved in all these things, which was lovely. Then in Buenos Aires one evening we did Kontakthof. The performances began half nine at night, at the earliest, or ten. Then it was one in the morning before we were finished. We showered, went for food, then went on to places where you could hear tango. In one an old woman was playing. There was a washing line where people hung up banknotes with clothes pegs and a little man was playing a bandoneon. He had a white cloth on his lap and his little bandoneon. He was very skinny and played so beautifully. In that bistro we met a dancer who took us to another place, where we all danced with him one after the other. You felt as if you could dance tango, because he did it so well of course. Then at seven in the morning we went back to the hotel, and that day we had a matinee. Then I slept two hours and went straight to training, then rehearsal and the performance. It was like being drunk. Everything was thrilling. It was amazing. Later on that tour I sometimes slept in the afternoon, before the performance. Then I woke up and wondered if it was morning or evening. It was really crazy.

Chapter 10.5

Santiago de ChileAnne Martin:

Then we arrived in Chile, Santiago de Chile. There we heard… We were meant to do two shows. But Pinochet was still there. Before we had flown there we got a message from Amnesty International saying, ‘Please don’t go to Chile because you are representing Germany.’ We talked about it in the group, but it was only Arthur Rosenfeld who thought we shouldn’t go. We decided we were still going to play there. As we arrived we heard that now we’d only be having one show. The second had been cancelled. We didn’t know why. We also heard that the seats were very expensive, and then we all decided to do a performance on the next day for the students and anyone who couldn’t pay, up in the ballet studio: Sacre, but without the earth. It was very powerful. All these young people were sitting around and we danced Sacre for them. After that, not sure how we managed it, perhaps because we didn’t have a show that day, they rented a bus and we went out to the countryside. A few of the students came with us. I spoke a lot to one of them. He said, ‘It was so important that you came. It’s so important that you performed, that we got to see something. We’re cut off from the world.’ Ok, politics is one thing, but this human interaction was incredibly important. Then I knew we’d done the right thing meeting these young people, and giving them the chance to see something different, taking the chance to speak to these people.

Chapter 10.6

Chile and Kurt JoossRicardo Viviani:

In Santiago they have a Kurt Jooss tradition, with people like Ernst Uthoff, Lola Botka. Did you meet any of them?

Anne Martin:

Jean Cébron danced there too. Yes, an elderly man came, but just to watch.

The name you just said. [Ernst Uthoff] Yes, I think so. Actually Pina met Ronald there, but we didn’t know. She didn’t say a thing. In Brazil there was a man hanging around with her the whole time, but I didn’t like him very much. He always had his toothbrush in his jacket, (points to breast pocket) on one side. (facial expression: ‘unconvinced’) Then we went to Peru and then to the final leg of the tour [Columbia, Venezuela]. Arnaldo came from Venezuela; his whole family came. Then Mexico at the end.

After that we had a bit of time. I stayed in New York for a few days, with Urs and Beatrice, and Pina returned to Chile. (laughs)

Chapter 10.7

Ronald KayAnne Martin:

At some point, back in Wuppertal, she told me she had met someone. I said, ‘Not the man with the toothbrush?!’ ‘No. Heaven forbid!’ (laughs) Then she was pregnant, while we were making Bandoneon. But she didn’t tell anyone. She wore her baggy shirts. At some point in the spring she told us, and Mechthild was upset she hadn’t noticed, and that Pina hadn’t said anything, but she was already five or six months pregnant by that point.

Chapter 10.8

Time off in New YorkAnne Martin:

The three of us stayed simply to be in New York for a bit. I don’t think we’d performed yet in New York then. We were in a tiny hotel, all three of us. We saw Chorus Line, and just looked around a bit. That time we didn’t stay so long. It was another time we stayed longer – no, that’s not true, we did stay a while. I had a friend, Peter Kowald, who was living there for a few months with a painter, and I went there with Dominique Duszinsky and stayed with him. With him I went to music improvisation bars, met a photographer who is now very famous, but at that time she had a black eye from being hit. What’s her name? I’ve forgotten the name. Anyway we got to know the underground life with Peter.

Chapter 10.9

Music from South AmericaRicardo Viviani:

You got back with all those impressions: South America. Lots of music. Did you collect music?

Anne Martin:

Yes, I started in Asia. I have always loved traditional music from every country. I used to ask around – in South America I asked around too – for very traditional music, not folkloric stuff; there’s an important difference to me. It’s the music they don’t sing for tourists: laments, lullabies and songs you just sing. After that I was much more focussed in my searches. At one point in Peru with Pina, we were in a tiny town almost countryside, where there were lots of indios, almost only indios, where you could dance. It was almost dangerous for us, because to them we were like tourists. You couldn’t pretend you were one of them because we were all much taller. Someone had their bag stolen. It was a bit like that. We couldn’t really talk because they didn’t speak our language. We listened to other music. In Chile we heard Mercedes Sosa in a bar. Was she singing? Now my memory’s playing tricks on me. We met her, but I’m not sure if she was singing.

Chapter 10.10

InstrumentRicardo Viviani:

Did you carry on playing yourself? What was your relationship to music?

Anne Martin:

No, during that period I wasn’t playing, because originally I did music with my mother. Then, as I said, my parents wanted me to do a diploma in teaching piano, but I didn’t. In Cannes I still played a bit of piano, but you have to practice the piano a lot. Earlier I had practiced seven, eight hours a day, but then I wanted to dance, so I gave that up. But later, in ’83 I think, lots of people in the group suddenly started playing an instrument. This was after my time out with hepatitis. Dominique started plying the cello, Ed the violin, Francis and Jean Sasportes played saxophone, and a friend of someone in the group found me a little accordion from a family – a child’s accordion. I took it everywhere with me. But that was later. When we performed the first time in New York we were staying in the Edison Hotel and in the mornings before we went for rehearsal we all played our instruments. No-one wanted a room next to Ed Kortlandt because he had only just started; it was ‘eeeehhheee, eeeehhheee' (sings like a screeching violin). It was hard work. One day I went out and the cleaning lady was there, a fat mama, and she looked at me and said ‘You didn’t play today. I want to hear you play every day.’ We each had an instrument with us. It was after that that the thing with Nelken and the accordion came about.

Chapter 11.1

Questioning Dance itselfRicardo Viviani:

OK, let’s do one thing at a time. We’re still on Bandoneon. It has so many dance references. What was the process like?

Anne Martin:

I think that was the period when Pina was really questioning movement. She just continued with what she had found. With Bandoneon – firstly Rolf had died, she had met Ronald and she was pregnant; I think she knew that. It’s a piece that’s about waiting. Waiting for something. When we did that thing with Dominique where he had his hand on my belly, I think she knew she was pregnant. But we did that – I don’t know why, any more – in response to some question or another she asked. But I don’t know which question any more. It related to this sense of waiting, and childhood memories and just listening to music and standing against the wall waiting. I think it’s a very powerful piece. I never actually saw it. I was always in it, but never saw it.

There was also a great moment when we were doing a stage rehearsal. She didn’t know how… She had these enormous photos of boxers and she wanted to get rid of them. She wasn’t sure if she really liked them or not. At some point during the stage rehearsal we were dancing in pairs, which comes in the piece, just paired dancing. Suddenly the light went out – it was late at night – and the stage lights came up, and the stage hands came and started removing the pictures. Pina didn’t say, ‘Stop. The rehearsal’s over now.’ We sensed something, I think. And then we just carried on. That stayed in the piece. It’s the end of the first half. She really had the genius just to take that: ‘Ah yes, that’s right for this moment.’ I think the more she went on, always with a lot of fear – she was afraid too, didn’t know, wasn’t sure – she learned to trust that insecurity. I often think about that today, trusting that insecurity. You can be unsure, but you know that at some point, when you approach it really authentically, with body and soul and love, then the ideas come.

Chapter 11.2

Artistic legacyRicardo Viviani:

Really that’s a very untypical way to work, when you’re in the theatre world or the opera. How did that influence you later, that freedom to embrace the unknown?

Anne Martin:

After I had left, I started singing with musicians and at first I dreamt that she came to a concert and said to me, ‘No, you’re not real any more.’ I was really afraid that outside of her gaze I couldn’t stay real any more. I know now it isn’t a problem, (laughs) but at the beginning I did dream that, at least once. Then I slowly made my way and stopped dancing for eight years. I was singing. I had to get to the essence, what remains when you have nothing left. I didn’t want to train any more, in the sense of raising my legs. I’d had two children. That sporty side of it was never my thing, although after a few years my body did gain that motricité [reflex motor skills]. Gradually I acquired a taste for teaching it to other people. At one point someone really trusted me and said, ‘Here’s a group of students, theatre students. You have three weeks. You can work how you want with them and show something at the end. You can do what you want.’ It was a very good way to start again. Then I did that for seven years, and I had the feeling I had a big bag of things I could just take out to start working with other people. When I arrived in Lyon, we had to make a piece with the students every year. I never had the feeling I was very creative, on my own I mean, but year after year… Now I love that way of working. I have a group of people. I only work with musicians, with live music. That means I listen to a piece of music, images or questions come to me, then I ask the students, and out of that comes the choreography. This way of working, which I learned from Pina – I can’t imagine working any other way. I can’t imagine coming and saying, ‘Ok, now we’re doing that, that and that.’ This way of trusting people: she never said that to us, but I still learned because I was always watching and involved with the whole work process. I don’t think I imitate her, but my creative process is related. When I have a group now, I love not knowing what will come out of it. I know something will come out, because I trust the people. That’s wonderful.

Chapter 11.3

From two to one production every yearRicardo Viviani:

Bandoneon was the first year…

Anne Martin:

…when there wasn’t a second piece. Ok. Then we were in Avignon and before or after that, Israel. Then I must have danced for Pina in Café Müller for the first time in Israel. I’m not quite sure any more. At any rate, that was a terribly difficult time. There was a ghastly run in Bremen. After that we went on tour to Australia. There I started going yellow. (laughs) Malou says, ‘Anne you’ve got yellow eyes.’ I didn’t know what was going on. I was just tired, tired, tired. When we got there I had swollen feet. It took eight days for the swelling to ease. Normally on tours I went out looking at things and all that. I was just exhausted. I just sat there, went to the show then back to my hotel room. I didn’t know what I’d got. It turned out to be hepatitis, and after the tour I went to hospital, for five, seven weeks, a long time. That was the time they worked on Walzer which is why I wasn’t part of the creative process. Soon after that I was back on my feet again quite quickly, thanks to the brother of my ex-boyfriend, Gérard, who built my strength back up with Chinese medicine. Really very quick: one month afterwards I was able to dance Sacre in Amsterdam – but I was very thin. I’m not exactly fat now, but then I was really thin. When I came out of hospital I tried to do a grand-plié and (gestures ‘collapse’) nothing held up any more. Well it came back.

Chapter 12.1

Five hours of Nelken (Carnations)Anne Martin:

I think it was the summer afterwards we went to Avignon. Malou wasn’t there any more, and I did one part for her in… No, that was a year later, sorry. I was still very thin. It took a long time till I put any weight back on. I had the energy, but not much else. Walzer was over and the next year it was… Nelken. Nelken was crazy. You probably have the dates for when we did the premiere in Munich. We did a dress rehearsal in Munich which lasted five hours. I admired that about Pina, that she had the courage just to show where she was at, not to think, ‘My God, I have to get the piece finished.’ The piece was not finished. At the dress rehearsal in the tent it was wonderful, people were sitting all around us. It lasted five hours.

At the start of the creative process for the piece I was still very, very thin and she was fascinated by how thin I was, and she just asked me – I was in my underwear – ‘Can you drink a glass of water?’ She thought you’d be able to see the water (gestures down her stomach) going down. (laughs) There were things like when the men said, each in their own language, ‘That is a woman.’ And I was just rather thin, in my underwear. None of that stayed in the piece. The only thing which stayed in was this skinny woman with an enormous accordion. But at the time I wasn’t playing that role yet.

We did this dress rehearsal, then the shows. The summer afterwards we were in Avignon – with Nelken (Carnations) too – and it still lasted four or four-and-a-half hours. It was very long. We had a whole passage with McDonalds cups we poured water into. We talked about what we do when we pee. That was funny. There were some beautiful things too. I’m not sure when, I think it was a year later, she took the piece up again and cut some things from it which were nice but not necessarily crucial to the piece. Now the piece lasts an hour-and-a-half without a break.

Chapter 12.2

RevisionsRicardo Viviani:

You said that 1980, for instance, was never changed. And other pieces?

Anne Martin:

But that’s the only piece which was changed a long time afterwards.

No, no other piece, just Nelken. Walzer wasn’t changed either.

Although Walzer – Can I go back to Walzer? (laughs)

Walzer was just after my hepatitis and they did the premiere in the Theater Carré in Amsterdam. I wasn’t in the piece: I just watched it. It was like a circus, but made of wood, within a building. The audience sat on three sides and watched the performers from above. It was very powerful every time Jan came up to the front – except it wasn’t up front, it was down below – and said things, or when the performers walked as if in an equestrian dance in very particular lines, and the neon lights were at the side so they were lit from below. It was as if in every face you could see the animal in the person. It was really, really great. It was never like that afterwards, even when people were sitting on the stage, because afterwards it was always like on a normal stage. That effect from the Theater Carré in Amsterdam was never repeated. It was really, really amazing.

Chapter 12.3

Watching and learningRicardo Viviani:

There you suddenly had the chance to experience it from the outside. Do you have any other memories from other times when you gained new insights into the work?

Anne Martin:

Yes, 1980 for instance. At the beginning, when a new piece had been created, all we were thinking was, ‘Where are my props? Where do I need to be?’ and all that. Later, after dancing it 70 times or so, you have a bit more time to look at it.

And in 1980, one day I see three men and Janusz carrying a harmonium right onto the stage. And with the light, and the way it was, I thought ‘My God, they’re bringing on a coffin.’ That was the image which came to me initially. That’s so great. I think in these eight pieces everyone can see what currently moves them, and that’s quite right. You can’t say, ‘Yes, she was thinking of a coffin and that’s what she did.’ It was created a certain way, and I can see it a certain way, although till then I’d thought they were carrying a harmonium into the middle.

Chapter 12.4

Sounds and meaningAnne Martin:

Another example was, working on Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehört [On the mountain a cry was heard] everyone could bring a poem or a piece of music. I had got hold of a cassette, I’m not sure from whom any more – in those days you had audio cassettes – with sounds from the air raids on Wuppertal during World War II. So that was full-on. I took it to Pina and said, ‘I want to share this with you.’ She listened to it and said, ‘Nah, that’s too intense. We can’t use that.’

At some point later she just asked a question: ‘Full moon?’ Nothing else: ‘Full moon.’ Beatrice went right to the back and cut a round moon from a piece of paper. She pinned it to the wall and played a wolf. (howls) Later, in the piece, I saw this from the wings and thought it was a wartime siren, signal for people to take cover.

This way of transposing a reality into something poetic, through other means, that’s what touched me the most. I like to work like that. You can talk politically about things, sure. That’s one thing. But you can also introduce things in different ways, on another level, which perhaps works for longer and deeper than just saying it so. (gestures ‘straight up’) That’s my view.

Chapter 12.5

Tacit agreementRicardo Viviani:

Pina was also very careful never to describe her pieces. Did she tell you, or discuss how it was better to leave things open and not explain them?

Anne Martin:

No, she never discussed it. Once in an interview, while I was still there, she said, ‘It’s got nothing to do with psychotherapy.’ That’s true. She really never talked to us about her work, analytically I mean. When I saw that film by Anne Linsel in 2006 where she talks about her work for the first time, says what she wanted and what she sensed, talks about the early years in Wuppertal and all that, I heard it and thought that we’d known all that but she had never spelled it out. We knew it though. All she said was things that we knew without her really needing to have said them. Particularly in a time when – I’m living in France now, and dancers and choreographers are required to explain their work, to be capable of talking about their work. The dancers have to know where they’re going. It’s all just bullshit. (laughs) Every step forms the path, and there is no path (gestures a path straight ahead) you just walk along.

No hay camino, el camino se hace al andar. [There is no path; the path is made by walking.]

Chapter 13.1

Talking about the workRicardo Viviani:

Of course young choreographers tend to have financial problems. You need a strategy to get round all that, for yourself as an artist.

Anne Martin:

That’s tricky. I’ve talked to a few young choreographers who studied with us about this. There is a particular way to say the right things. Then they can do something completely different. But they have to express their stuff in words so the people who give out the money understand it. It’s a game. If you take it as a game, it’s ok.

I think Pina was incredibly lucky that Wüstenhöfer trusted her implicitly and gave her the opportunity to do what she was born to do.

Chapter 13.2

Contact with Arno Wüstenhöfer?Ricardo Viviani:

Did you have contact with Arno Wüstenhöfer?

Anne Martin:

No, I met him just once, only because he was there with the others.

Chapter 13.3

The legacy of the Folkwang SchoolRicardo Viviani:

We’ve reached somewhere around 1982/83. In this period did you have any contact with the Folkwang world: Hans Züllig, Jean Cébron?

Anne Martin:

Right at the start of my time there Jean Cébron came and gave us some classes. There was perhaps five or six of us in his class. Most of them didn’t want to work with him because he had a very precise and very in-depth way of working. Most of them just wanted dance-company training; they wanted a warm-up. And we were from such different worlds, I can understand that now. But when I arrived in the classes I realised everything I was missing. Beatrice and Lutz were immersed in it; they had studied there. So several times when I had some spare time I took the bus to Werden in Essen. He gave me individual lessons so I could gradually understand more about his work. In Arien there was a movement Pina did with her hand (gestures: reaching down then two upwards accents). It took a long time for my body to understand that. I saw it and I saw that I couldn’t do it, and Beatrice showed me it. I loved those lessons with Jean. I knew after a class with him you could do any kind of dance, modern or classical. He explored every quality of movement in depth. He was so thorough, so complete, his way of teaching. He was very, very precise, and when someone was interested in his work he gave his all. That was really great for me, that work with him.

Chapter 13.4

Daily classes and Hans ZülligAnne Martin:

He gradually came less often, because Züllig was there too. It was simpler for me. Züllig did a lot of work on the back, but not in as much detail as Jean Cébron. A few times Jean Cébron taught us a bit of ‘death’ from Jooss’s Green Table. He had such a quality to him, it was incredible to watch him.

I sometimes went to join in with their training. Sometimes they were doing classical too, pointe – no, I didn’t join in with the pointe work, but classical classes sure. There were just four women in the classical classes and they complained when one more person joined them – and I came from Cannes where we were at least 40 in a class – crazy! Jean and Züllig really were amazing. But they came less and less often. Züllig a bit more. At the start we had Strolka teaching classical. That was very heavily classical, as it were. After that we had Christine Kono, who still comes. She is amazing. And Janet Panetta from America, who was super. In my time we didn’t have Corvino yet. I know he came a lot later. Afterwards, when I came to join Malou, I went to the Folkwang School and did training with Jean a lot when he was doing it. After I finished here I did a piece with Malou where I sung. That was lovely. Otherwise I’ve never taught there. I was there a lot to see Malou’s pieces and the FTS shows. I knew Susanne Linke very well too, because she often danced Sacre with us. She was with us on the Asia tour, for instance. Now we often have Erasmus students from the Folkwang School in Lyon and a few of my students go to the Folkwang School too.

Chapter 13.5

Jooss, Bausch and FranceRicardo Viviani:

What kind of awareness is there, in Lyon too, for this historic German modern dance? Back then no-one knew Kurt Jooss had existed, a whole branch of modern dance, especially in the first half of the twentieth century. It was consciously separated, with American modern dance on the one hand and Jooss and Laban on the other. Are people aware of all that today, and teaching it?

Anne Martin:

Yes, when Pina first did performances in France it was a shock to the French, even though The Green Table had been shown in Paris in the 1930s. When I was in Cannes the only people you knew about, as I said, were Nikolais, Cunningham, a bit of Alvin Ailey, nothing else. A bit of Limón, but I had no idea about Limón. Later, in the 1980s, Trisha Brown and a few others became known. But France always needed ten years to acknowledge people. When Pina arrived it was a shock, but lots of young choreographers started this kind of dance with little gestures. (demonstrates hand gestures) It was pure imitation; they had no idea about the working process. The young dancers were so excited by Pina’s work. In the late 1980s, early 1990s, there were a lot of workshops about Jean Cébron, Hans Züllig and Kurt Jooss and that whole movement organised in Lyon, at the Biennale de la Danse or in the Maison de la Danse, in Paris too. The workshops were given more from a historical perspective, although some people identified with it and took it further, but on a small scale. When I started teaching in Lyon, in 2003, I noticed this was something that wasn’t present. It’s important that I’m there, to offer another side, although I’m not doing exactly what they did. Of course I developed my lessons with the students I had. Still, something important is being used by people. I think it’s right that I’m there. Later, in the 1990s, the people from Belgium came along, who also worked with human beings: Vandekeybus, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. When I saw a piece by Cherkaoui at the end of the 1990s I thought, ‘Good that a bit of Pina has carried on in things like this.’ That continues in Belgium. I’ve noticed that in France it’s very highly valued.

Chapter 13.6

Choreography centersRicardo Viviani:

Can I ask a bit more about that time? In the 1980s, with the decentralisation of dance in France, and various choreographic centres, did that have an influence on the company? Did the tours also take in the cities with these centres?

Anne Martin:

I’ve never thought about that, but it’s true, we did go to Nice – no other cities. (laughs) Lille too. I think that was all to do with Jack Lang. He did a lot for dance, earlier on in the 1970s at first, with André Malraux and the Maison de la Culture. At the end of the 1970s Jack Lang really did a lot for dance to make sure these choreographic centres got going, that there was even the possibility for Dominique Bagouet to go to Montpellier to do something there. Did it really have much to do with Pina? Perhaps it’s like so often in history, that movements happen simultaneously without directly influencing each other. I don’t know.

Chapter 13.7

Paris as a partner to the TanztheaterRicardo Viviani:

It just occurred to me, this subject. At any rate Paris became a very important partner to the Tanztheater Wuppertal.

Anne Martin:

Yes, because Jean Gérard Violette was a very loyal kind of person. When he liked someone, he always stuck with them. That was great bonus. Thomas Erdos too, the Hungarian agent, a good friend of mine, and of Pina’s too of course: he did a lot to ensure that everything could happen, every year – in Paris, Avignon, in France altogether.

Chapter 13.8

Thomas ErdosRicardo Viviani:

When did you first meet Thomas Erdos? Another person who’s not with us any more.

Anne Martin:

During our first shows in Paris. He very quickly became a wonderful, good, old friend. In Nice, in 1983 or ’82 I think, we went for food together with Stéphane Lissner, who is now the director of the Opéra de Paris. At that time he had just… the place opposite the Théâtre de la Ville? – Châtelet! He had been the director in Nice and had just taken over running Châtelet. Thomas was a real counsellor and a lovely friend. Someone I valued highly.

Ricardo Viviani:

Is his influence on the company down to this friendship or also his work as an agent?

Anne Martin:

I never really asked what he did as an agent, but he was always there, always active in the background. He was never at the front of the stage, as it were. He was at every performance. He was… To be honest, I’m not sure exactly what he did. I’m sure he did something. He worked at the Théâtre de la Ville and had his office near the Paris Opera. He probably helped with the tours. He always had his little address book in his pocket, here (shows book in trouser pocket) with all his addresses, in Hong Kong, in Los Angeles. (laughs) He was a true gentleman, really.

Chapter 13.9

AccordeonRicardo Viviani:

Did you already have your toy accordion for Nelken (Carnations)?

Anne Martin:

It wasn’t a toy; it was a small, children’s accordion. But I didn’t go on stage with it. The one on stage was a real accordion, but I didn’t play that role, as you know.

Chapter 13.10

Instrument in CarnationsRicardo Viviani:

That wasn’t your instrument? This idea of a woman…

Anne Martin:

No. But she knew I took my accordion everywhere with me. In Viktor I played the accordion, that little accordion, but that was later.

Suggested

Legal notice

All contents of this website are protected by copyright. Any use without the prior written consent of the respective copyright holder is not permitted and may be subject to legal prosecution. Please use our contact form for usage requests.

If, despite extensive research, a copyright holder of the source material used here has not been identified and permission for publication has not been requested, please inform us in writing.